You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

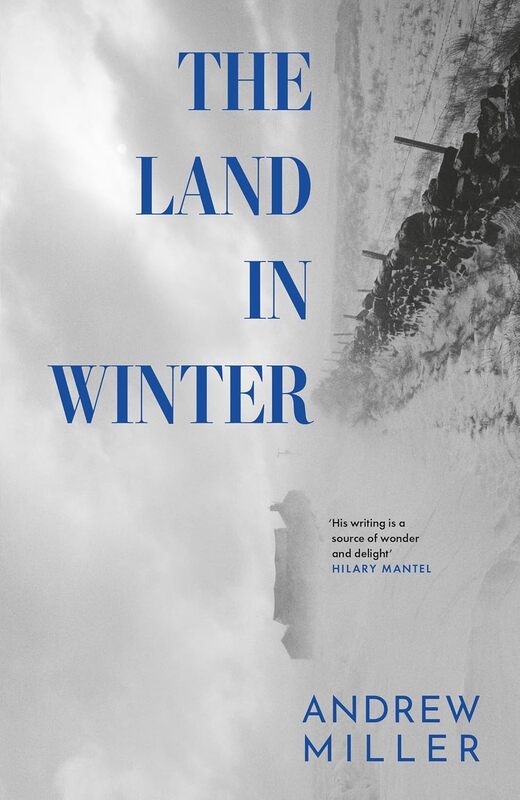

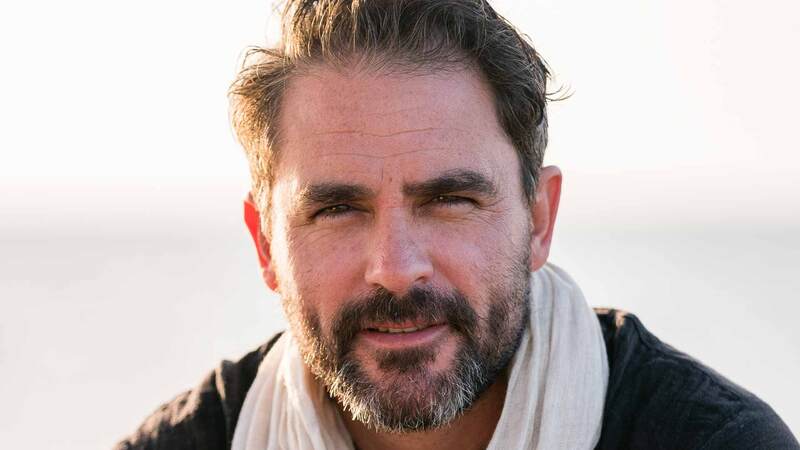

The new novel by Andrew Miller, set in a frozen 1960s Britain, explores a society on the brink of change

Andrew Miller‘s exquisite new novel The Land in Winter is set in a frozen 1960s Britain on the cusp of the Swinging Sixties.

The winter of 1962-63 was an extraordinary one. Snow that first fell in December was still lying in March during one of the coldest and longest winters on record. The Land in Winter, Andrew Miller’s exquisite 10th novel, unfolds against this seemingly never-ending chill. It is the story of two young married couples, both expecting a first child, living in a small village near Bristol; Eric, a country doctor, and his wife Irene, who has led a hitherto sheltered life; and Bill, determined to reinvent himself as a farmer, who is married to former Soho dancer and showgirl Rita.

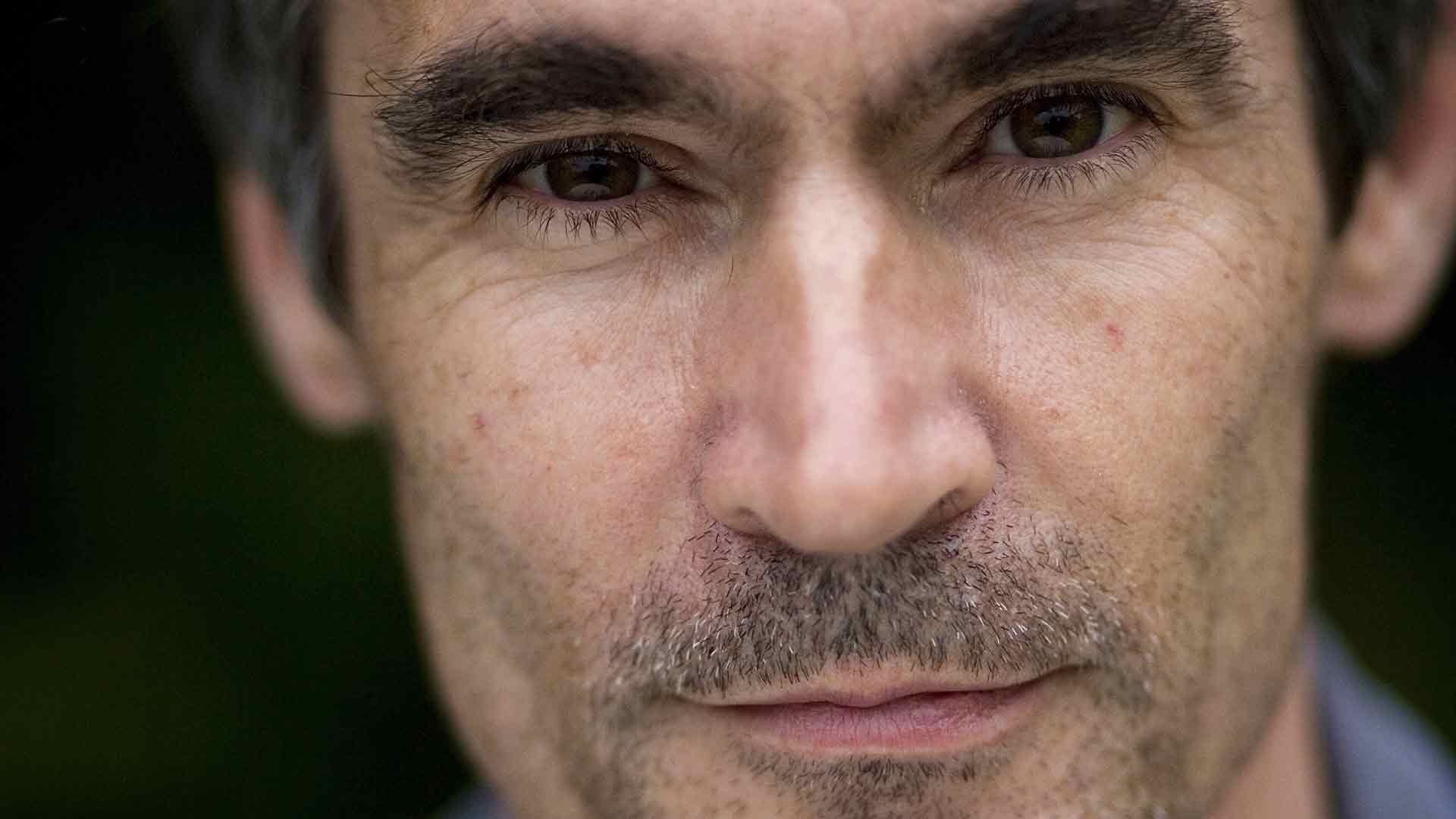

When we meet at a restaurant in a sweltering central London on what is, in a poetic inversion, the hottest day of the year, Miller tells me he was two during this bitter winter. Not exactly living memory then, but he did feel “a sense of this being something I was remembering. It feels like if I reach out as far as I possibly can and then stretch a little bit further, I can touch it. I can have some faith that, at a sort of cellular level, I was there.”

The Land in Winter is a slow-burn novel—“digressive”, says Miller. “I wanted it to be something that was not afraid to slide sideways as well as going forwards.” It is also compelling, built of the tiny details that make up the lives of others. “For me it’s always about that kind of intimacy. It’s about being close to lives and to the physicality of lives, which is always my way in.” Miller recalls his dad complaining that “there’s always people going to the toilet in your books!”—prompted, he thinks, by a scene in his multi-award-winning 1997 début Ingenious Pain which featured a character atop a chamber pot. “It’s partly just a way of rooting people in their physical reality. Clearly there’s a little more to physical reality than that, but it was a complaint of his. Families have a way of criticising your work in a slightly different way to anybody else,” he laughs.

Miller’s father was a country doctor, as is Dr Eric Parry in the novel. “I’m going to have a little bit of a struggle with brothers and sisters over whether this is a depiction of our father,” he says. “It’s not, but there’s enough of an overlap for me to perhaps find myself in some trouble.”

The Land in Winter was partly inspired by a story Miller’s mother once told him, about her early married life as a rural GP’s wife. It made him “curious”, and he became very interested in the early 1960s, a time when society was on the brink of massive change.

It feels like if I reach out as far as I possibly can and then stretch a little bit further, I can touch it. I can

have some faith that, at a sort of cellular level, I was there

In the novel, the 1960s may be on the verge of swinging, but things are definitely not swinging yet. At a party, it is Acker Bilk on the record player (the English trad jazz clarinettist famous for his striped waistcoat and bowler hat), not the Rolling Stones. Miller cites David Kynaston’s vivid social history On the Cusp: Days of ’62 and Penelope Mortimer’s Daddy’s Gone A-Hunting, about a housewife going slowly mad, originally published in 1958 but now reissued by Persephone Books (“She’s such a good writer”) as key to illuminating the period.

Each of the characters seems to be trying to live the life that is expected of them, to conform in ways against which, over the course of the novel, they will all find themselves chafing. In shaping themselves to fit, each will come under immense pressure. Dr Eric Parry, ostensibly a pillar of the community, is having an affair with the glamorous wife of a wealthy man. Rita, a showgirl in the vein of Mandy Rice-Davies, has seemingly left her past in the clubs of Soho far behind, but the voices in her head have followed her to Somerset.

“For me, fiction generally is about our relationship to the bigger life. Whether we want it or not, whether we feel brave enough to have it, whether having it is disturbing—which it often is, of course. And what the bigger life might mean. For Eric, the bigger life involves his infidelity. But what that involves is the kind of intensity that he doesn’t find in the rest of his life—in his marriage and more generally, perhaps. They are all at an age when maybe what they had hoped for, what they had expected, hasn’t quite come off and they are going to have to readjust in some way.”

Question of settings

Throughout his career, Miller has moved between historical and contemporary settings—from the late 1990s West Country in the Booker Prize-shortisted Oxygen to pre-Revolutionary Paris in the Costa-winning Pure. “You choose something in a sense because the subject will let you write, it will draw the writing out of you. I started writing Ingenious Pain not because I had some obsession with 18th-century medicine, but because somehow it drew things out of me, it let me write. With this, I was partly working in reaction to my previous book The Slowworm’s Song where I felt very constricted by the first-person narrative. I wanted to write very freely; I was going to have fun. So, I just moved forwards, at quite a brisk pace, writing the first draft. Like crossing stepping stones on a river, but not worrying about seeing all the stepping stones at once, just the one that I needed next.

“One of my ambitions is always to write a book that no one can say what it’s about; it would be completely impossible to say what it’s about, as the moment you say one thing, you have to correct it, it would never settle. So, while yes, it is about Eric and Irene, Bill and Rita, every time I write a book, I’m ‘in’ the writing. I’m thinking, how can I make something that sings? How can I write about life, what’s my way into a life that will open it out in some way?” Which, he acknowledges drily, can frustrate those who would prefer an elevator pitch. “For me it is about how can I find a way of writing that opens up this world, these lives.

“I want those moments when—and you get them sporadically throughout a novel, because nobody does 400 pages of it, that’s just not possible—but you get little moments where you feel as a reader: ‘This is authentic, this has touched something.’ Maybe it’s a half page—a half page would be good, actually—so I guess I write in search of, or in pursuit of, those moments.”