You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

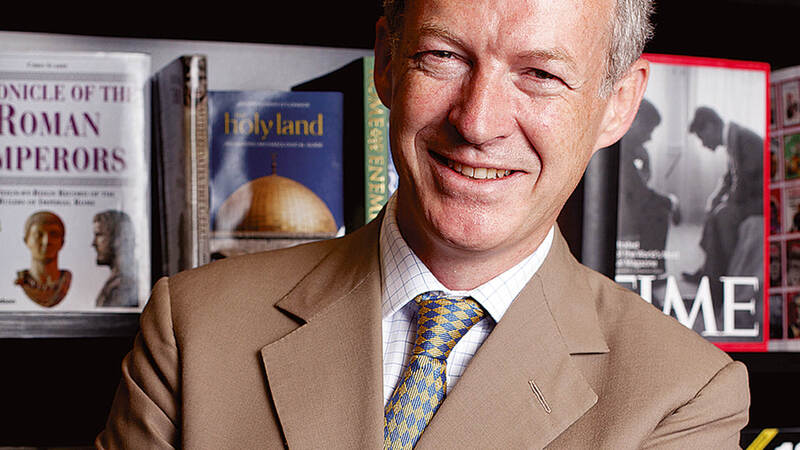

Vaseem Khan | 'I wanted to write a book just for myself, and I put in there all the things I love'

After the success of his Inspector Chopra series of novels, Vaseem Khan’s new hero is India’s first female police detective, working the beat in Mumbai in the 1950s

Vaseem Khan was reading about the history of Mumbai as part of research for his successful Baby Ganesh Agency series—which stars the newly retired Inspector Chopra and the elephant he inherits on his last day of work—when he came across a fact that made him sit up.

“I discovered that not all white people left India in 1947, after partition,” he says on a Zoom call from his home. “That had been my impression, which shows I’m just as ignorant as the next person, in spite of having lived in India. I hadn’t realised that tens of thousands of Brits and Europeans, and a few Americans, stayed in India post- 1947, and were there for at least a decade, maybe more.”

The essence of what you’re trying to do as a historical crime author is to tell the truth about a particular period, without turning it into some kind of encyclopaedic rehashing of what happened

He was immediately intrigued. “This is a fascinating period. Gandhi had been killed recently, the partition riots were hanging over the country, and yet we have got all these foreigners still here—who many Indians blame for instigating a lot of this—living privileged lives,” he says.

So, as crime writers do, he thought: “What if I bumped one of these people off, and created a mystery around it?”

Khan’s’s new thriller, Midnight at Malabar House, opens on New Year’s Eve 1949 in Bombay, as Inspector Persis Wadia sits alone in the police station. Then the phone rings. There has been a murder, of the English diplomat Sir James Herriot, and Persis, India’s first female police detective, takes the case.

“While I was reading about this period, I uncovered India’s first actual female police inspector, Shanti Parwani,” says Khan. “She was a constable back in the 1940s, she didn’t graduate to full inspector until 1960, but once I read about this woman, I thought to myself, ‘What must it have been like?’”

Having lived for 10 years in Mumbai in his twenties, Khan knew “that it is a very patriarchal society. And I tried to imagine what it would have been like for this police woman seventy-odd years ago, being the very first in an institution that really didn’t want her, one that was incredibly male-dominated.

“The Indian Police Service doesn’t have a very good reputation—even today, it’s considered to be quite corrupt and incompetent,” he says. “So I’m trying to imagine this woman working in that environment, and then I thought, ‘Why don’t I use her as the vehicle for this mystery that I want to write? Why create another Inspector Chopra-style character? Let’s do somebody who, right from the very beginning, is going to be of immense interest to us, simply because of who she is, as opposed to me having to develop a dramatic backstory for her.’ She is the back story, she is the drama, the fact that she’s a woman.”

Challenges to overcome

From the start, Khan shows how difficult Persis’ role is. She keeps on her desk a framed quote from a newspaper from when she was appointed: “The commissioner’s experiment in catapulting a woman into the service might well mirror our fledgling republic’s forward-thinking ideals, but what he has failed to consider is that in temperament, intelligence and moral fibre, the female of the species is, and always will be, inferior to the male.” But she rises above it all deliciously, refusing to be pigeonholed or put aside, in a way that is glorious to watch. Khan writes: “For millennia, we have been told what our role must be: wife, mother, daughter. We are all those things, but we are so much more. Men like you think you can stop us. Go ahead and try. Have you ever tried to stop the monsoon?”

Having written his five Inspector Chopra novels from a male perspective, Khan found it “difficult, but not intimidating” to take on a woman’s story. “It always comes back to, ‘Can you create a character that is reasonably authentic, and in their own way, in spite of any of the quirks that they might have, likeable?’ If they are, then the old rule is that readers will forgive you the odd mistake that you might make.”

He took advice from the queen of historical fiction, Hilary Mantel, when it came to writing a novel set in the past, recalling a lecture from which he took away that “the essence of what you’re trying to do as a historical crime author is to tell the truth about a particular period, without turning it into some kind of encyclopaedic rehashing of what happened”.

Khan adds: “The first draft of that book probably had twice as much historical exposition, compared to what we finally ended up with.” He wrote the second novel in the series in 90 days during the first lockdown.

Khan had wanted to be an author since he was a teenager, writing his first novel at the age of 17, a science-fiction comedy which was “duly rejected” by the agents he sent it to “because it was rubbish”. His “typical Asian parents” had other ideas for him—he was going to be a doctor, a lawyer, an accountant. “They said, ‘You’ve had your shot now, off you go to university.’”

A passage to India

He studied accountancy and finance at the London School of Economics, and went into management consultancy after he graduated. That led to 10 years in Mumbai in his twenties, consulting for a hotel group building India’s first environmentally friendly five-star hotels. He wrote another four novels while he was out there, everything from a “big literary novel” to contemporary romance, couriering them back to English agents and reaping “another crop of rejection letters” each time.

“I got 200-odd rejection letters over the course of 20-odd years, from 17 to the age of 40, when Hodder gave me a four-book deal,” he says. “For many, many years I thought, ‘OK, this next book is going to crack it for me’, but I did get to a point when I thought, ‘Maybe this will never happen, you’ve been rejected by everybody under the sun.’ But it was just a passion for me.”

He came back from India when his mother got cancer. Settling down in the UK with his Indian wife, he felt nostalgic for Mumbai, and decided to write a novel set there. “I wanted to write a book just for myself, and I put in there all the things I love: crime fiction, the colour and life of Bombay—and an elephant. It was madness to do that but I absolutely fell in love with these amazing creatures while I was out there. I thought, ‘I’m never going to get published anyway, so just stick it in.’”

He sent it out and landed an agent, Euan Thorneycroft at A M Heath, and then an offer from Hodder. “I still find it slightly surreal, receiving a call like that, to say that after 23-ish years of rejection, the industry has finally opened its doors and said, ‘Yeah, we’re going to publish you.’”

Khan has worked at University College London’s Jill Dando Institute of Security & Crime Science since 2006, and has no plans to stop. “I do the day job, not out of necessity but because I absolutely love being there. This sounds cheesy, but I like the fact that we’re all working together to try and make the world a safer place.”

Plus it’s sometimes useful, as a crime writer. “Once I went to a colleague of mine, and I asked her, ‘What do I have to do to burn somebody alive?’” he grins. “It was an interesting way to start a conversation, but she’s a forensic anthropologist, so she was more than happy to explain to me everything that happens to a body once it’s set alight.”