You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Victoria MacKenzie in conversation about mining forgotten voices in her medieval-set début

In her impressive début, Victoria MacKenzie tells of two tenacious medieval women whose stories were nearly lost forever.

One morning in 1413, two women meet for the first time in the city of Norwich. Their faces are hidden from each other, separated by a black curtain. One has come to the other seeking spiritual advice. Margery, the seeker, has left her 14 children and husband behind in a Norfolk town. Ever since the traumatic birth of her first child, she has had visions of Christ but she is treated with derision by her husband and neighbours when she speaks of them.

The woman concealed behind the curtain is Julian, an anchoress (that is, a woman who has retreated from the world to live a life of prayer and contemplation) who has not left the cell, adjoined to a church, to which she is confined for 23 years. She has been having visions—“shewings”—of her own, but has told no one.

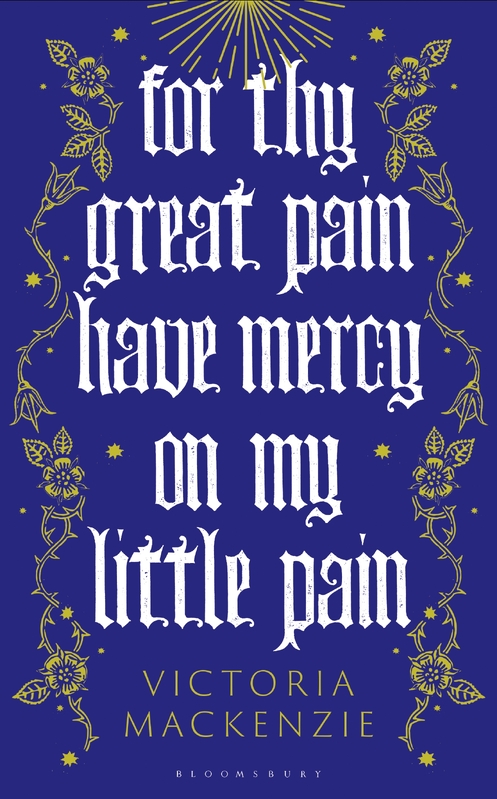

Victoria MacKenzie’s hugely impressive début novel, For Thy Great Pain Have Mercy on My Little Pain, imagines the lives of these women who lived more than 600 years ago—Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe—and their voices ring across the centuries, clear as a church bell.

I’m fascinated by what it might have been like to put yourself in a single room for so many years

As Julian and Margery tell their stories, we are plunged into the late-medieval world. In Julian’s calm, measured words, we understand what it is to survive the plague when those you love do not. Though she too is from a prosperous merchant family, Margery’s voice is earthier, her life seemingly more turbulent, as she struggles with motherhood and her visions, and the accusations of heresy. But lest that sound very bleak, their words are often full of light humour and both women are sustained by a powerful faith. MacKenzie has also filled her novel with tangible detail, the physicality of life in the medieval world—the textures, things eaten, noises heard from the street outside Julian’s cell.

A canvas to be filled

When MacKenzie speaks to me over the phone from her home in a Fife fishing village—originally from Sussex, she has lived in Scotland since studying as a postgraduate at St Andrews—she explains that the novel grew out of her interest in Julian of Norwich, who wrote Revelations of Divine Love, a work of theology that is also the first book known to be written by a woman in the English language (it is still in print today). But it was Julian’s life as an anchoress, rather than her religious writings, that drew MacKenzie in. “I’m fascinated by what it might have been like to put yourself in a single room for so many years. What effect might that have on a person, both physically but also emotionally and psychologically? What might motivate a person to do such a thing? It seems so extreme.”

Very little is known about Julian of Norwich, beyond the text that she wrote. MacKenzie points out that we don’t even know her real name—she took the name Julian from the church of St Julian in Norwich that her cell adjoined. “So it felt like, for a novelist, there was this huge canvas that could be filled in.”

Once MacKenzie started researching Julian, she came across Margery Kempe, another extraordinary woman living in late-medieval England, who dictated her life story (she was illiterate) to an amanuensis. The Book of Margery Kempe is the earliest known autobiography in English (and again, is still in print today). MacKenzie remembers that her voice “blew me away when I started to read her book”.

I wanted to keep it as direct as I could, to keep the focus on their voices. I didn’t want to paraphrase their conversation, I just wanted to lay it out on the page

When MacKenzie discovered that the two women had actually met, “that’s when I felt the novel actually start to take shape. I realised I wanted to build the novel around the meeting and I wanted to imagine what these two incredibly different, but tenacious, women might have said to each other.”

In For Thy Great Pain Have Mercy on My Little Pain (the title is taken from a plea in The Book of Margery Kempe), the women speak in alternating sections, directly to the reader, relating their life stories. MacKenzie took great care “deciding where to break the sections, how to juxtapose the different things they were talking about…to give the reader the occasional jolt through moving quickly from one tone—the more refined voice of Julian, who is very serene and in control—to suddenly back to the chaos of Margery Kempe and all her unhappiness.” The novel culminates in the two women meeting and the narrative changes into an “almost script-like form”, explains MacKenzie. “I wanted to keep it as direct as I could, to keep the focus on their voices. I didn’t want to paraphrase their conversation, I just wanted to lay it out on the page.”

Serendipity

For Thy Great Pain…was written in less than a year. MacKenzie put pen to paper at the beginning of lockdown in 2020 and finished it in February 2021. She sent a partial to literary agent Sam Copeland on 1st March, and he asked to see the rest of the manuscript the very same day—and offered her representation the day after. This all sounds suspiciously like an overnight success, until I discover that For Thy Great Pain… was actually written during a break from the novel she has been writing, on and off, since 2014.

The subject of Brantwood, the novel she has been writing for so long, is the Victorian art critic and polymath John Ruskin. As so little is known about Julian, MacKenzie says: “I think imaginatively I just felt such freedom, whereas writing about someone like John Ruskin who for one thing has published more than 200 books and pamphlets of his own, and the amount of material on Ruskin—just his biographies—is vast!” Brantwood will be published by Bloomsbury in 2025.

Extract

I fear that my neighbours are right, that it is the devil inside me, making me think that I see Christ. Master Aleyn, my friend the Carmelite monk, said to me, “Margery, you must go to Norwich to see the anchoress and hear her counsel.” But now I am here I wish I was back in Lynn. The streets are crowded and both men and women use foul curses. I saw a man put a live mouse between his lips as if it were the sacred host, cheered on by a group of sailors.

I tutted as I passed them and one of the men called out to me as if I were a strumpet. My maidservant has found us an inn, but it is not a comfortable place. I sit on the filthy bed and think I have never felt more wretched. For the first time in many years I wish I was at home with my children.

But this is my last hope. The devil won’t have my soul. The anchoress will surely help me.

As MacKenzie notes in the epilogue to For Thy Great Pain…, The Book of Margery Kempe was lost for many centuries, before a 15th-century manuscript (not the original but a near-contemporary copy) fell out of a cupboard in a country house in 1934 when a guest was looking for a ping pong ball. Revelations of Divine Love was smuggled out of Julian’s cell and preserved by a succession of women, including an order of Benedictine nuns in France, before being lost again. The original is still missing but three copies survive. She writes: “These two books, both so nearly lost forever, are two of the most important books written in the medieval period—and they are both by women.”