You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

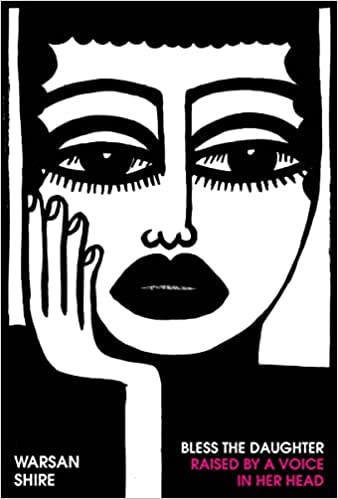

Warsan Shire on Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in Her Head

Caroline Sanderson

Caroline SandersonCaroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

The first full-length poetry collection from Warsan Shire is being hailed as an ‘important cultural moment’ by publisher Chatto.

Caroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

“Poetry is a balm for the heart. It makes you a more thoughtful person, it widens your imagination, it makes your heart bigger.”

Via Zoom from her home in Los Angeles, where she lives with her Mexican husband and their two children, Somali-British poet Warsan Shire is talking about what poetry means to her. “I don’t have a clear memory of bein g introduced to poetry—it was almost as if I inherited it in some way,” she adds.

Shire’s star in the poetry firmament has been rapidly ascending since she published the first of two rapturously received chapbooks, Teaching My Mother How to Give Birth, in 2011. The title poem caught the attention of one Beyoncé Knowles-Carter, who invited Shire to write poetry for the award-winning film that accompanied her album “Lemonade”. Shire also collaborated with Knowles-Carter on Disney film “Black is King”, and wrote the short film “Brave Girl Rising”, highlighting the voices and faces of Somali girls in Africa’s largest refugee camp. She was awarded the inaugural Brunel International African Poetry Prize in 2013, and served as the first Young Poet Laureate of London.

At my local library I was opened up to the work of other Black poets: it was like my brain was exploding because I didn’t know there was so much poetry out there

In March 2022, she publishes her first full-length poetry collection, Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in Her Head, backed by a marketing and publicity campaign fit for what Chatto is calling an “important cultural moment”. And indeed Shire’s electrifying poems have the resonance of instant classics (as the extract on this page, taken from her poem “Home”, shows). Drawing on her own life and heritage, as well as on pop culture and current affairs, Shire raises up in dignity the lives of immigrants, mothers and daughters, Black women and teenage girls. While her poems are often shocking, taking in subjects such as the homesickness of the displaced, the violence of war and female genital mutilation, her writing is also supremely seductive. Among those who have already lavished praise on Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in Her Head are Bernardine Evaristo, Pascale Petit and Roxane Gay, who has described Shire’s poems as “fiercely tender gifts”.

Born in Kenya in 1988 to Somali parents who fled the civil war in their country, Shire came to London at the age of one and grew up in Harlesden in west London. While she didn’t visit Somalia, the country where she was conceived, until 2013 (a blissful homecoming experience when she remembers her cheeks aching from “smiling non-stop”), Shire grew up utterly immersed in its culture. “We had these massive photographs on the wall all over the house which showed the country both before and during the war—it was like a vigil. I realise now that my father was trying to anchor us there,” Shire tells me. She was also an early eye-witness to the effects of conflict because throughout her childhood, refugees from that same war passed through the family home. “These were people who had fled for their lives and so my mother rightly felt it was her responsibility to welcome as many of them as she could to stay with us.” Only as an adult did Shire come to realise just how traumatised many of them were.

An insular child and an avid reader, Shire tells me that she was scribbling down little poems from a very young age because it was an “everyday tradition within my family. My Mum was always reciting poetry, and when my grandmother called from back home, she would also recite a poem to me.” However it was only when she studied the work of poets such as Chinua Achebe, Carol Ann Duffy and Simon Armitage at school that Shire discovered that being a poet was an actual job. “All of us thought that we were going to end up working in Ikea. So my mind was blown. And then my English teacher told me about a haiku competition for secondary schools in Brent.” Shire entered and won. “Then at my local library I was opened up to the work of other Black poets: it was like my brain was exploding because I didn’t know there was so much poetry out there.” Shire credits fellow poet Jacob Sam La Rose, who she met through a workshop at her youth club when she was 15, for helping her to believe in her talent and take her vocation seriously. He still acts as an editor and mentor for her work.

Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in Her Head comprises poems written over the past decade, a watershed time in Shire’s life during which she has been working through mental health issues that have plagued her since childhood, including OCD and an eating disorder. Following therapy, the binding theme of the collection—an exploration of girlhood—emerged through the voice of a girl who in the absence of a nurturing guide makes her own stumbling way towards womanhood. There are moments when Shire herself appears, including in the opening poem “Extreme Girlhood”, while other poems, such as “My Loneliness is Killing Me”, portray people she encountered in childhood, who are recalled with the help of family photos brought with her when she moved to the US.

Her unique voice sounds so clearly from her poems, that I’m amazed when Shire tells me that she can only write while listening to a single song on repeat, or while watching films, a habit she says was born from trying to write through the noise created by the younger sisters she looked after throughout her childhood. “I could never write in silence. My favourite thing in the world to do is to put on a film and write while I’m watching it. And then when it finishes, and I look back at what I’ve written it has nothing to do with what I’ve been watching. It’s like an out of body experience: afterwards I think: ‘Who wrote that?’ It can be quite creepy but it’s also why I’m constantly reading or listening to music or consuming art. I could not do anything I do without beautiful pieces of work that other creatives have put their souls into.”

Home

No one leaves home unless home is the mouth of a shark.

You only

run for the border when you see the whole city running as well.

The boy you went to school with, who kissed you dizzy behind the

old tin factory, is holding a gun bigger than his body. You only

leave home when home won’t let you stay.

No one would leave home unless home chased you. It’s not some thing you ever thought about doing, so when you did, you carried

the anthem under your breath, waiting until the airport toilet to

tear up the passport and swallow, each mournful mouthful making

it clear you would not be going back.

No one puts their children in a boat, unless the water is safer than

the land. No one would choose days and nights in the stomach of a

truck, unless the miles travelled meant something more than journey.

I ask Shire if she consciously thinks of her audience when she’s writing. She laughs. “If I’m honest, it’s all very selfish. I’m writing for me and for my mental health, trying to make sense of things for myself. But I also know that it’s weighed heavily on me since I was a child that the stories of people I knew were being told without humanity.” And indeed the poems in Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in Her Head form a rich tribute to Somali culture, weaving in words from the Somali language. But perhaps Shire’s most outstanding achievement is to make such personally rooted poems speak so vividly of the experiences of people across many cultures, particularly those who are displaced or marginalised. This is poetry that has the power to create empathy, a quality which often seems lacking in these turbulent times.

Shire hopes her poems will resonate with young people in particular. “I’m so grateful to have had my whole life perspective changed by the authors I read and the teachers I met. So I hope I can help something similar happen for others. Especially young people, who feel that there’s nothing to look forward to. I want to show that there is something out there for them, especially in literature, reading and writing. Because poetry saved my life.”