You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

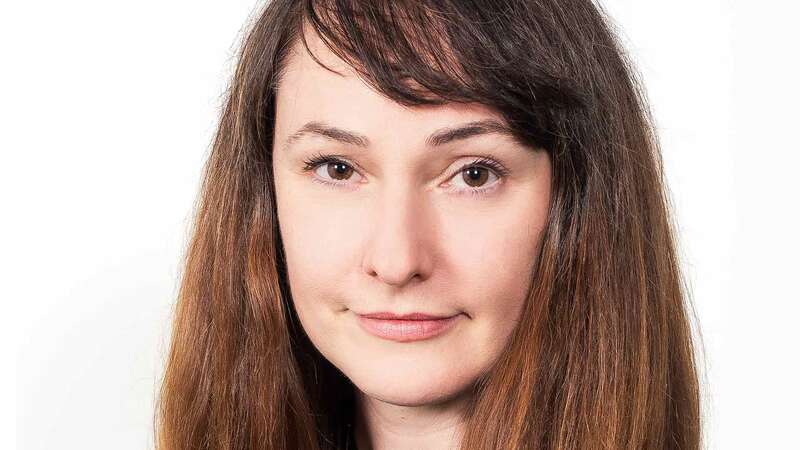

Will Maclean | 'It would be amazing to see a ghost, but I never have'

Will maclean’s chilling novel The Apparition Phase is a haunting tale of troubled twins set in England in the 1970s

Tim and Abi, the twins at the heart of Will Maclean’s story of a haunting, The Apparition Phase, are obsessed with the macabre: “There was nothing we didn’t know about the Drummer of Tedworth, or The Screaming Skull of Bettiscombe Manor, or the Poltergeist of Borley Rectory, and 100 other strange and peculiar stories.”

So they decide to fake a photograph of a ghost, drawing it on their attic wall, “smudges of chalk suggesting a damaged, furious face in which two awful eyes glared”, calling it into being with a creepy little rhyme. But the fallout when they show the photograph to classmate Janice will resonate through their lives; Janice faints, and then won’t accept it when they explain the photograph was fake, falling into a trance and telling them, in a gloriously unnerving scene: “I see it returning, and it will never let you go. It will always be with you.”

When I write, I try and reduce a story to a sentence, and then to a word, and then you kind of unpack that word for all it’s worth. And for this one, it was, what is it like to be haunted?

Set in 1970s England, narrated by an adult Tim, The Apparition Phase is properly terrifying, in the best way, a thrilling, chilling dive into the “genuinely, malevolently inexplicable”. The perfect October read. I finished it late at night, gone midnight, and found myself worrying about the psychic conjurings I had summoned myself by reading about its vindictive spirits. I went to sleep with the light on.

Maclean had four unpublished novels and a successful career in writing for television behind him when his agent urged him to try focusing on what he loved. Like his haunted twins, he collected books about ghosts and the paranormal as a child. What he wanted to write, it turned out, was a ghost story, so he sat down and wrote a list of the “crème de la crème” of the genre: The Turn of the Screw, The Haunting of Hill House, Beloved, The Shining, The Ghost of Thomas Kempe and House of Leaves.

“There are only four basic types of ghost stories,” he says, talking on Zoom from his home in Crouch End, north London, where he lives with his wife and young daughter. “Not knowing one of the characters is a ghost is quite common, like in ‘The Sixth Sense’. It’s all in someone’s head, and they’re mad, The Turn of the Screw is the best example of that. It’s definitely a real ghost—Shirley Jackson. But the most common structure, and this is all of M R James, is somebody transgresses or does a bad thing, something that’s against the code of their society, and they are then punished in a supernatural way, anything from being killed to being ontologically disturbed. So in Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad you have Parkins, who is never quite the same again. And it’s almost like the worst thing that could possibly happen.”

This, he decided, was the kind of story he wanted to write. “When I write, I try and reduce a story to a sentence, and then to a word, and then you kind of unpack that word for all it’s worth. And for this one, it was, what is it like to be haunted? What is haunted like, as a state, what are we haunted by that’s real, that’s not real? It was very rewarding to bring all of that out. That seemed to be the key: we are haunted by the people who aren’t there any more. We’re haunted by the ways our lives could have gone.”

The Apparition Phase has its genesis in an article about 1970s hauntology Maclean read in the Fortean Times, the magazine devoted to strange phenomena. Two months later, the magazine’s letters page was dominated by responses to the piece. “I thought, people don’t know about this as much as I thought, and the emotional terrain of it is definitely there to be explored.”

He wrote a list—another one—of things which appear in stories of that era. Twins. Haunted houses. Psychical research. “It almost seems, from the literature of that time, that ghosts are on borrowed time, that they’re going to be claimed by science very soon, that pretty soon we’ll know that they’re sound waves or something,” he says. “It never comes to pass of course, but back then it felt like it was going somewhere.” Then, he says, he got Tim and Abi to talk to each other.

Frightening your readers isn’t an easy thing to do, however. Maclean looked, again, at the “people who do it really well”—M R James, Robert Aickman—and tried to unpick what they were doing. “You get the impression that they know all the answers to the story, and then they knock out bits of the logic of it, so you’re left to assume. So I felt when I wrote this, I had to know every single thing about it,” he says. “It’s like doing a little magic trick in someone’s brain, so it’s left to the reader to make those connections. And you can make those connections as obscure as you like, or as close as you like, but you are leading the reader to a conclusion.”

Maclean says he gets asked a lot if he believes in ghosts. He doesn’t really answer (“it’s such a large and complicated question”) but hasn’t seen one himself. “I like that people can entertain those things, no matter how rational they are—like if you stay somewhere you don’t like and you have a feeling about it. Those things are universal, I think, no matter how rational people are,” he says. “I’m fascinated by ghosts. It would be amazing to see a ghost, but I never have.”

Perhaps this is because, unlike Tim, he’s never been to a reputedly haunted house, or done a séance. And—wisely, perhaps, given the outcome for his protagonists—he has no plans to. “No matter how childish or weird these myths seem, you still wouldn’t do it. If someone said, ‘This object is haunted’, would you have in your house? No matter how rational you were, you would have to be alone at some point with that object.”

Around the houses

Maclean, who is originally from the Wirral, studied English Literature at Bristol, the first generation in his family to go to university. He did “a lot of manual jobs” once he graduated, “the usual string of writer’s jobs”. In 2006, he landed his first gig writing for television, going on to work as a scriptwriter for names including Alexander Armstrong, Al Murray and Tracey Ullman, and for children’s television.

His previous four (unpublished) novels were written on the side. “I think with the first stuff you write, there’s a lack of generosity towards the reader. When you’re younger, you just go, ‘I know what I’m doing’—but you don’t. You don’t try and involve the reader as much as you probably should,” Maclean says. “It was the same with writing comedy. You can be articulate and you can be funny in person, but it’s not the way you are on the page, and it takes so long for those two things to collide. It’s such a frustrating process.”

He points to his earlier comment, that he got his characters Tim and Abi to talk to each other as a way to get The Apparition Phase going. “It takes 12 years to learn that idea, because it’s not a natural thing to do,” he says.

Next up isn’t another ghost story, but “it is pretty creepy”, he promises, although the pandemic has somewhat delayed it; his wife is a head of production in television, so Maclean spent a lot of time with their daughter while his wife took Zoom meetings. The Apparition Phase might have been released in hardback in the heart of lockdown, but it was still a wonderful experience for its author. “I’ve got no experience to compare it to, so as far as I was concerned, I was overjoyed. That thing you always dreamed of—when you go to a bookshop and you see your book there—that took about six weeks to happen, because you couldn’t go anywhere,” Maclean says. “But two weeks ago, I saw it at Crouch End library, and I was almost in tears.”

Book extract

For the very first time, I was forced to look at the things my sister and I got up to, our macabre experiments and reading habits, the gleeful bleakness of the imaginary world we shared, and wonder—is this right? Is this normal? And later that night, in my pyjamas, my bedside light burning brightly, I forced myself to look again at the photo of the Ghost Monk of Newby, considering for the first time the possibility that it was a fake, a double exposure rendered by some process I was ignorant of. That meant that someone had had to plan and stage the photograph, just as we had done with ours. It meant that someone would have put together the costume that the ghost wore, cloth mask and all, and someone would have had to wear it.

The idea that a person would do this, would design this terrifying thing with no purpose other than scaring people, was in some ways more troubling than the idea that it might be a picture of a real ghost. If the Ghost Monk of Newby was a prank, it was not an amusing or enjoyable one. It was malevolent and unpleasant, a manifestation of someone’s darker thoughts and feelings, feelings that couldn’t be expressed any other way.

And if that were the case—what, then, was our ghost?