You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

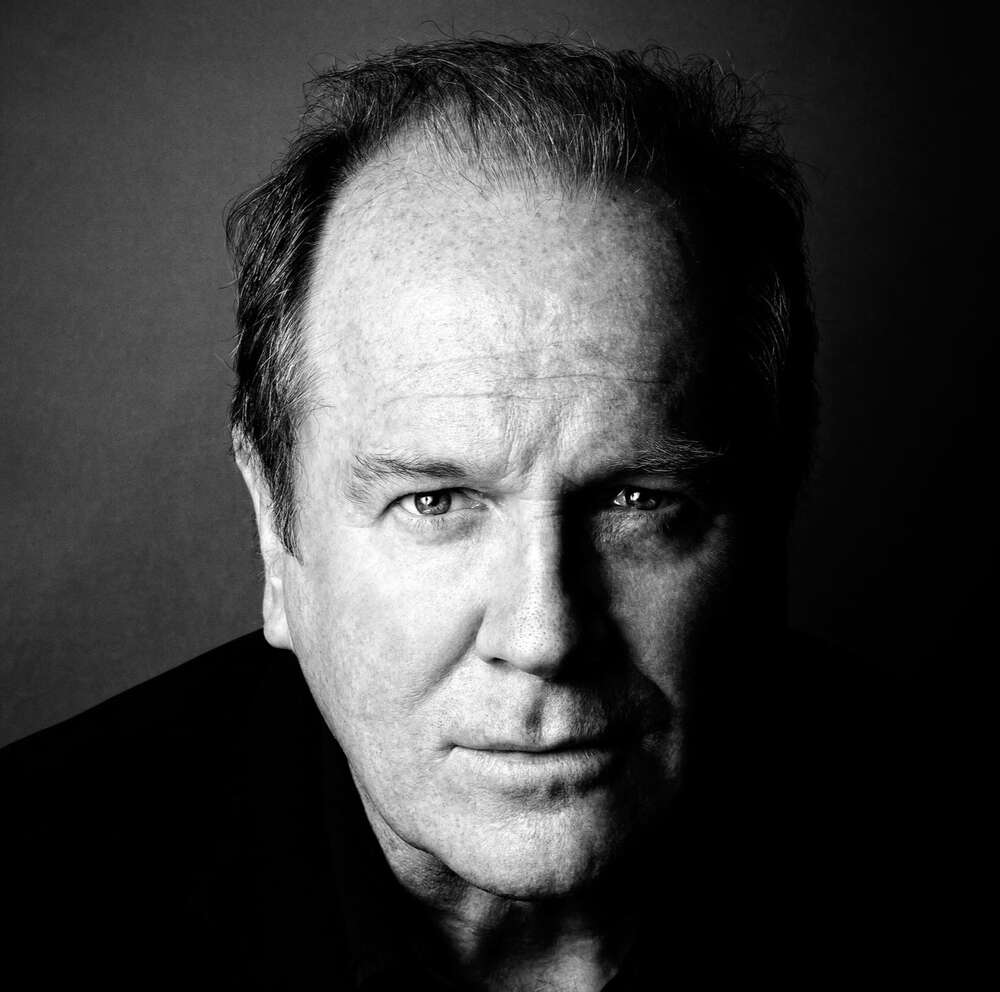

William Boyd | 'You and I can take photographs as good as David Bailey or Henri Cartier-Bresson'

April Fool’s Day 1998, novelist William Boyd published a hoax biography of a 20th-century American artist, Nat Tate, which was sufficiently convincing to take in a number of prominent art critics. One of the elements that made the hoax so persuasive was Boyd’s use of anonymous photographs, drawn from a discarded family album he had picked up at an antiques fair in France. “Nat Tate” was in fact the family’s chauffeur; his true name and story unknown.

That book, notorious in its day, prefigures Boyd’s latest novel Sweet Caress, which tells the eventful life story of photographer Amory Clay, born in 1908 and living through many of the major events of the 20th century.

Amory, after surviving a dramatic near-drowning during childhood, goes on to make her way successfully in the world via a photography career that takes her from 1920s Berlin to the glamour of New York, the London of Oswald Mosley’s Blackshirt riots in the 1930s, Second World War France, and finally 1960s Vietnam. She also navigates a love life that ranges from youthful love for her gay Uncle Greville to eventual marriage with Sholto Farr, a Scottish aristocrat.

The novel follows the same “cradle to grave” life story structure Boyd employed in his novels The New Confessions and Any Human Heart, possibly his best-loved book. Boyd says it’s difficult technically to pull off—“a certain amount of smoke and mirrors, clever elision and cross-cutting”—but that the tale of a single life can be as engaging as any spy thriller (such as his hit novel Restless and his most recent book, James Bond adventure Solo). Certainly, Sweet Caress is richly entertaining, though deeply concerned with war and its effects, and shot through with a black comedy Boyd says he has inherited from Chekhov’s short stories via the novels of William Gerhardie and Evelyn Waugh—a “gimlet-eyed view of the absurd cruelty of life”.

But Sweet Caress has an additional dimension; it is interwoven with the images supposedly taken by Amory, from the scandalous society portrait with which she first makes a splash in London, to candid shots of lounging Berlin prostitutes, or photographs from scenes of battle. Playfully, the images take the reader through a kind of photographic history of the 20th century—from Brassa√Ø’s low-life portraits, to Cecil Beaton’s society shots, the fashion photography of Richard Avedon, or the war photojournalism of Lee Miller or Catherine Leroy.

The photographs mesh very naturally, and in an understated way, with the text, giving it a realism that is entirely invented. Many readers will find themselves assuming that Amory —or at least her fellow photographers Hannelore Hahn or Mary Poundstone, or her lover Jean-Baptiste Charbonneau —have some background in historical fact. None do so.

Boyd loves photography. He thinks it is “so democratic” as an art form—“you and I can take photographs as good as David Bailey or Henri Cartier-Bresson”—and that it’s a very interesting, open profession as far as women are concerned. “We’ve all heard of a few famous women photographers, but actually they are legion. Women thrived alongside men, there was no glass ceiling—particularly in continental Europe. Gerda Taro in the Spanish Civil War; further back, in the 1920s, women photographers were everywhere, working professionally.”

But writing about photography raised an issue for him: “When you write about any kind of artist in a novel, you’ve got to think, for a photographer or a musician, the fact that you never see or hear their work is very unsatisfying. Having done it [used anonymous photographs] in Nat Tate, I thought, ‘I can show Amory’s work and the people she meets and deals with.’”

The 70-odd photographs in Sweet Caress were carefully chosen from a hoard of some 2,000 images, sold at auctions or car boot sales or online. One was even found by a friend at a bus stop in Dulwich and sent on to the author. Some of the pictures were hard to find —almost all the surviving images of the conflict in Vietnam are press shots, rather than the anonymous photographs Boyd was looking for. “I think the ones I found are very poignant or funny or telling, particularly the ones of very young guys. I came across this stash of photographs where someone had obviously just taken [pictures of] his mates, and they look so young. You think, ‘These are the people who fight our wars.’”

I came across this stash of photographs where someone had obviously just taken [pictures of] his mates, and they look so young. You think, ‘These are the people who fight our wars.’

Choosing which images to use was “a fascinating parallel creative exercise alongside the writing of the novel,” Boyd says. “I wasn’t sure until I put them together in my first typescript how it would work; if they would fight against each other, or one would diminish the other. But almost immediately, I thought, ‘This works really well, it’s a most curious enhancement of the fiction.’”

He “hasn’t quite worked out”, he says, what is going on in the mixing of image and text. ”These are real people and real photographs, yet by captioning them and colonising them for my fiction, it has the effect of making the fiction more real.” It was important not to overdo it, to have “just the right number to season the narrative and make it come alive in a strange way.” Boyd says: “In a funny sort of way, I am waiting for the mass readership to respond and to say what it does for them. There are no real people in this novel, unlike Any Human Heart [which includes appearances from the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, among others], but all the same, the effect is the same—you can see a photograph of Sholto Farr or Amory’s mother and think, ‘Is this a fictionalised version of a real life?’ There’s the ocular proof of her existence.”

He muses further: “When I look back at those three books [The New Confessions, Any Human Heart and Sweet Caress]—and I put Nat Tate in, and make it four books—though there was no grand plan, [I see that] what I was trying to do was to show just how powerful fiction can be, so it occupies the real like a version of history, it has its own absolute verisimilitude . . .

“It’s all to do with fiction: life is mysterious, human beings are opaque—even your family, spouse, children, you don’t know what goes on in their heads. How do you find out what makes people tick? The answer is the novel. That’s why it endures and thrives, it’s the best art form for making sense of the human condition. It deals with the messy, random business of our lives, this common adventure we’re on, the human predicament. Fiction’s the best way of getting at the truth, however paradoxical that sounds.”

Photo of William Boyd: Trevor Leighton