You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Zoulfa Katouh discusses the importance of truth, representation and hope in her highly anticipated YA debut

Charlotte Eyre

Charlotte EyreCharlotte Eyre is the former children’s editor of The Bookseller magazine, and current children's books previewer. She has programmed ...more

Zoulfa Katouh’s ’love letter to Syria, Syrians and hijabi girls’—which is set during the Syrian revolution—is generating interest around the world

Charlotte Eyre is the former children’s editor of The Bookseller magazine, and current children's books previewer. She has programmed ...more

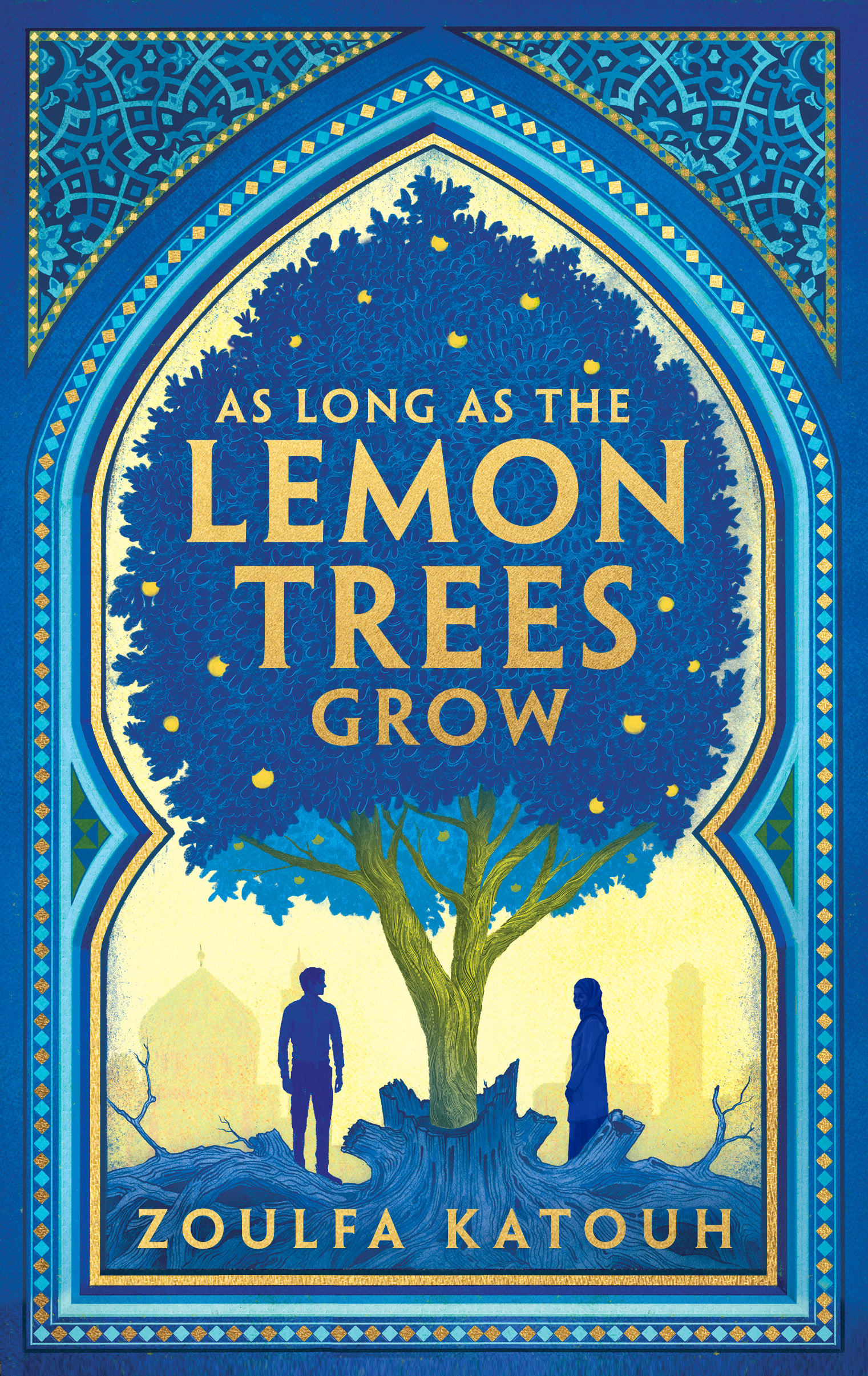

Searing. Gorgeous. Groundbreaking. Wrenching. Lyrical. Hauntingly beautiful. It is still three months until the publication of Zoulfa Katouh’s breathtaking début but these are already some of the adjectives being used to describe her YA book, which is billed as a love letter to Syria, Syrians and hijabi girls. Set during the Syrian revolution, As Long as the Lemon Trees Grow is a romance between Salama, a pharmacy student who volunteers at a hospital, and Kenan, a young man who documents the horrors of the war for the world to see.

Katouh was prompted to write the book after realising that many people in Europe didn’t even understand what the revolution was about, or the horrors that were taking place. “I split my childhood between Dubai and Switzerland and obviously in the Arab world everyone knows what is happening in Syria, but when I moved permanently to Switzerland people from Europe didn’t really know what was going on,” the Canadian national tells me when we meet in a central London hotel.

“The last time I was in Syria was in 2010. I was in Homs [where the book is set] and I still think about the people there. I can see some of their faces. Are they still alive? When I was asked about the war, I realised I needed to write this story.”

The character of Salama was inspired by the people who worked for the White Helmets, a volunteer organisation that gives aid and emergency care to Syrian civilians. Like them, Salama puts others’ needs before her own safety, working day and night on the front line to try and stop people from dying, before going home and taking care of her pregnant sister-in-law Layla, the only person in her family she has left. When she is alone she converses with Khawf, a sort of imagined companion, or spirit guide, who encourages Salama to leave the country. But when she meets Kenan and love blossoms, that decision is hard to make.

I don’t shy away because that would be disrespectful to the people who went through it. I have to tell the truth

Authentic Muslim representation was also really important to Katouh, and she wanted to show characters embark on a love story that feels true to the values she embraces. “I really wanted to show Muslims who don’t reject their religion. They are happy with it,” says Katouh, who wrote the book with young Muslims who don’t see themselves in books in her mind, as well as her 15-year-old self. “Kenan would have definitely been her fictional boyfriend,” she laughs.

For the same reasons, Salama is a normal girl who “wears her hijab and is happy with it”. Her creator is all too aware of the negative stereotypes about Muslim people that are propagated by the media, and hopes that this story can go some way to redress the balance.

The nightmares of war

Katouh doesn’t shy away from describing the horrors that war inflicts on innocent people—one part in particular, involving the death of a child who is beyond medical help, will make readers weep—but as she says, these things need to be shown. That scene was based on a real event, as were many parts of the book.

“I don’t shy away because that would be disrespectful to the people who went through it. I have to tell the truth,” she says. “And there are so many other stories, for example, one child was born during the revolution and when his family were able to flee, they were on a bus going to Turkey and someone was handing out apples. He takes the apple, looks at it, and says: ‘Is this a bomb?’ It’s heartbreaking.”

In the end of As Long as the Lemon Trees Grow Salama and Kenan get an ending which is hopeful, and happy in many ways, but when I ask about how other refugees adjust to life away from their country she confirms that, yes, many do struggle.

She tells me a story about when she was younger and met a woman who had left Syria three or four years previously. This woman was “stone cold” and closed off, and yet when Katouh met her a year later the same person was kind and smiling. “I realised that she was healing. She had left a war zone, her brother had been tortured to death, and I felt so bad that I had judged her… I gave Salama and Kenan a happy ending but that’s not the case for all Syrian refugees.”

They’re just refugees who ran away… it’s very, very scary

Our talk naturally turns to Ukraine and the war being waged there at the moment and Katouh says the world should absolutely help Ukrainian refugees, but that the difference in treatment they get compared to people coming from Syria or Afghanistan is “horrible”. Switzerland gave Ukrainian refugees free train passes, she says, and yet the opportunities for Syrian refugees in the country are limited. And her family knows first-hand the fear refugees have about being sent home: in the 1980s her father’s brother was sent back from Germany and was subsequently killed.

“One of the European countries is sending Syrians back to their country. And if they go back, they will be most likely imprisoned. And they’re very scared because they haven’t done anything. They’re just refugees who ran away… it’s very, very scary.”

Learning to write

Katouh began writing As Long as the Lemon Trees Grow in 2017 but had little experience and no connections with the publishing world. “I literally Googled, ‘How to publish a book’ and it said: ‘First step, write a book. Second step, find an agent… I was like, that’s quite general!”

Her first draft was “130,000 words of pain” but she soon realised the love story, which provides hope, needed to be brought to the fore. Her agent, Alexandra Levick at Writers House, helped during two years of rewrites but when the manuscript finally went on submission it sold in four days: Little, Brown pre-empted in the US and there were auctions in the UK, France and Germany. Eighteen foreign rights deals have been struck so far.

When I ask why publishers were so keen to work with her, she points out that she is the first Syrian YA author. “English isn’t a first language for many Syrians and I’m fortunate to have that as mine,” she says. In addition, as previously mentioned, Muslim representation is still lacking in Western literature. “There is a gap that hasn’t been filled and I’m honoured to be able to do that. Hopefully I, with my agent and with a lot of help from writer friends, have made something unique that people enjoy.”

And as for Syria? “I hope I can see it become free in my lifetime. I hope my people can be free soon. I pray for them but all I can do is help them with my words. I hope it brokers some change, however small, in the water. And if not in my lifetime, then in our children’s.”