You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Power of the platform

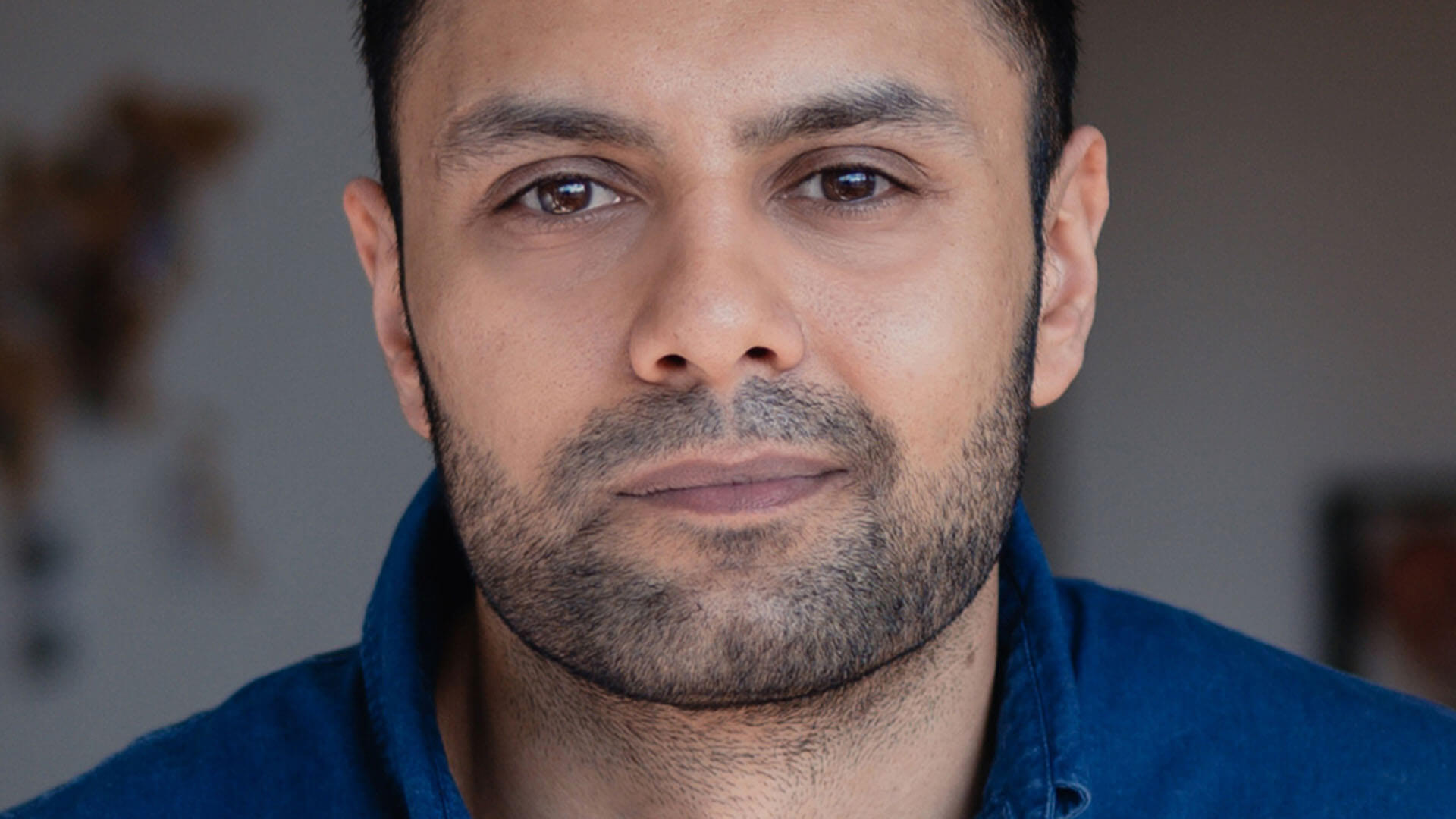

Mohsin Zaidi, author of A Dutiful Boy, discusses how the publication of underrepresented voices has the potential to transform lives.

To me, people of the book industry are the guardians of one of the oldest and most treasured artforms. This opportunity to speak directly to you all is not one I wish to waste. So instead of adopting a series of compelling points on the moral and ethical arguments for diverse representation, I’d like to tell you a story.

When Penguin’s WriteNow team emailed me on 29th November 2017 to offer me a place on the programme, my first thought was disbelief, followed quickly by this one: “Shit, I am actually going to write this book." The gravity of my decision to put so deeply private a story into the world—a story unknown even to many of those closest to me, and one which I knew might draw hostile responses, not only to me, but also to my loved ones—began to dawn upon me the following day. It was near-impossible to understand what it might mean to take such a step, and difficult to imagine the long-term consequences. My parents shared my concern but also hoped the book could help others avoid the heartache we had endured. With a preliminary green light from my family, I decided to focus entirely on the writing.

Event horizon

The anxiety about putting so much of my life and my family into the world returned in the weeks before publication, when it became a real event on the horizon, edging closer towards us. My family and friends gave steadfast support and the Penguin team—in particular, Rowan Yapp and Mireille Harper [both editors at Penguin Random House at the time]—helped to guide me through.

I decided to turn off all social media notifications, a decision that my partner, Matthew, disagreed with. Although it would of course mute any nonsense, he believed it would also shut out the positivity which, during Covid, would silence the only way to hear what people thought. To begin with, I stuck to my guns—and the decision helped. Turning off notifications silenced everything and in that silence I kept hold of a mental equilibrium. A handful of messages found their way into Matthew’s DMs and he suggested I reconsider my stance on notifications and unsolicited messages. “I’m scared,” I told him. “So are the people trying to reach you,” he replied.

Mixed messages

I eventually relented and, predictably, as someone writing about sexuality, faith, race and class in Britain, I received abuse. As determined as I was to keep the small minority of hostile messages in proportion, there were times when they eclipsed the many positive ones. I knew that my mental equilibrium was slipping as I stood on a train platform a few months ago. My phone alerted me to a message from a stranger and the alert sent me into a spiral. Do I read the message now, alone on this platform, or wait until I’m at home, safe and near Matthew? I took a deep breath and opened the message.

It was from a mother who had just finished reading the book. She told me that she came from a devout Christian family and that her son, who was also religious, had come out to her the previous year.

Diversity isn’t just about ticking boxes. By giving voices to the underrepresented, you are changing lives in ways none of us will ever fully appreciate

When the son told his mother about his sexuality, she had rejected him. She had believed that her son’s connection to God was false, and that man was made for woman. She told me that she felt ashamed that it took reading about someone else’s journey to fully understand her own. Every word she read was one she had lived, and she was regretful for failing to put her son at the centre of her feelings. This mother told me that she now accepted her son, loved him unconditionally and supported his endeavours to find a place for himself and others within their Christian community.

On that train platform I was reminded of my parents’ belief and my hope that sharing our story might help others. The fear and anxiety left me and the sense of being able to stop holding my breath, even for a minute, made me cry.

Out of respect for a family’s privacy, I can’t show anyone the message (the details of which have also been altered slightly); I can tell you, the book industry, about it. In so doing, I hope to illustrate the power in the platform you are the guardians of. Diversity isn’t just about ticking boxes. By giving voices to the underrepresented, you are changing lives in ways none of us will ever fully appreciate and, for that, I thank you.

Mohsin Zaidi is a criminal barrister at one of the top chambers in the UK. He is on the board of Stonewall, the UK’s biggest LGBT rights charity, and is a governor of his former secondary school.

A Dutiful Boy (Square Peg, £14.99, out now, 9781529110142) is Mohsin Zaidi’s personal journey from denial to acceptance: a revelatory memoir about the power of love and belonging. Growing up in a devout Shia Muslim household, it felt impossible for Zaidi to be gay. Despite the odds, his perseverance led him to become the first person from his school to attend Oxford University, where new experiences and encounters helped him to discover who he truly wanted to be.