You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Whitaker’s world

Last week David Whitaker, a former editor of The Bookseller and for a long time the head of the family that owned the magazine, died.

Last week David Whitaker, a former editor of The Bookseller and for a long time the head of the family that owned the magazine, died. Whitaker was well-regarded in the trade and, if judged by the tributes that came in following his passing, well remembered for his lasting contribution to the business. He was combative, opinionated, but often right. He led the creation of the ISBN system for cataloguing books, the Teleordering system that was well used by booksellers before the web superseded things, and put the force of the magazine behind campaigns against VAT on books and for libraries.

He was also progressive. As editor he introduced a policy of foregrounding women in the trade, through the way the magazine handled and commissioned stories. His contribution was just one part of a wider emancipation that also included the creation of Women in Publishing in 1979, and the launch of the feminist publishers Virago and The Women’s Press. In a 2008 interview, Whitaker recalled his satisfaction that at the time two of the three largest publishing businesses were run by women. “No need for that today,” he said of the policy.

I write this at a time when publishing is once again engulfed in a damaging discussion around diversity and representation, brought on by writer Kate Clanchy’s Picador-published award-winning book Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me, and in particular her reaction to legitimate criticism of that title for its use of racial and ableist stereotyping.

Having first rejected the criticism, bizarrely claiming that quotes had been made up and used out of context, Clanchy and her publisher Picador are now in retreat, as are some (though not all) of the authors who defended the book. “We want to apologise profoundly for the hurt we have caused, the emotional anguish experienced by many of you who took the time to engage with the text, and to hold us to account. We realise our response was too slow,” read a second statement put out by Picador, after the first proved inadequate. Clanchy says she has been humbled by the row and will now embark on a re-write.

A third statement, put out after this column went to press for print publication, further—and rightly—condemns the "ongoing abuse and harassment of many -- including the women of colour, Monisha Rajesh, Prof. Sunny Singh and Chimene Suleyman -- who have taken the time and emotional energy to voice their concerns online". An open letter now signed by more than 950 figures from the industry, also expressed its "complete solidarity with the brave writers who challenged this", condemning "all attempts to attack them and obfuscate and negate the veracity of their concerns"].

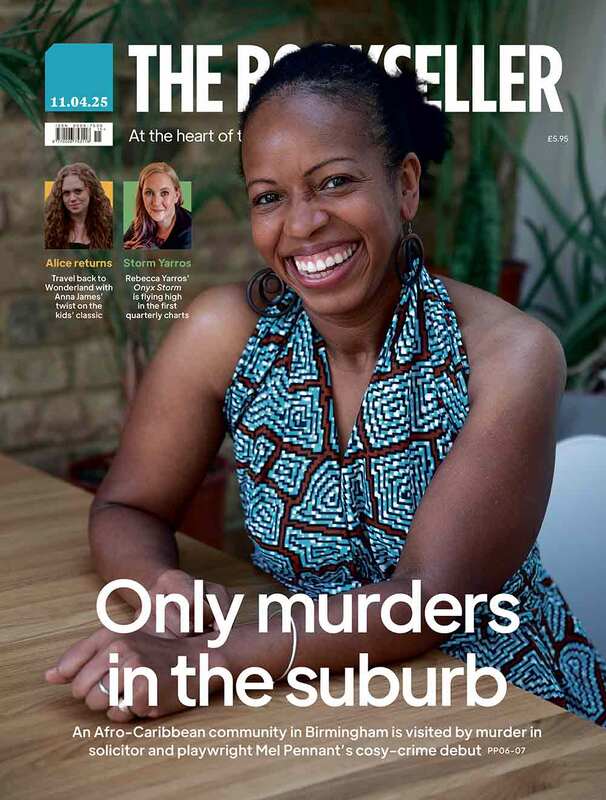

In April, The Bookseller published its first ever issue edited by a Black editor. For all of our progressive chops, this is a woeful record: and that it speaks to a wider systemic problem is no excuse. But with typical generosity towards the trade, this is what our guest editor Marianne Tatepo wrote in her opening letter: “We can’t fix a system we were neither careless enough to build nor empowered enough to dismantle. Allies, that job is yours. But we can urge you to listen up as we demonstrate, yet again, just how much this trail we’re blazing is worth fighting for.”

I am sometimes at a loss to explain the state we are in. I don’t know if David Whitaker ever faced a similar moment of cringe when he surveyed the trade, and its inability to live by its own values.

I know he positioned The Bookseller as an activist force at a time of great change, and although this is not the 1970s, the struggle we see playing out on social media today is our generation’s opportunity. I know too that when it matters most, there are too many who are not listening.