You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

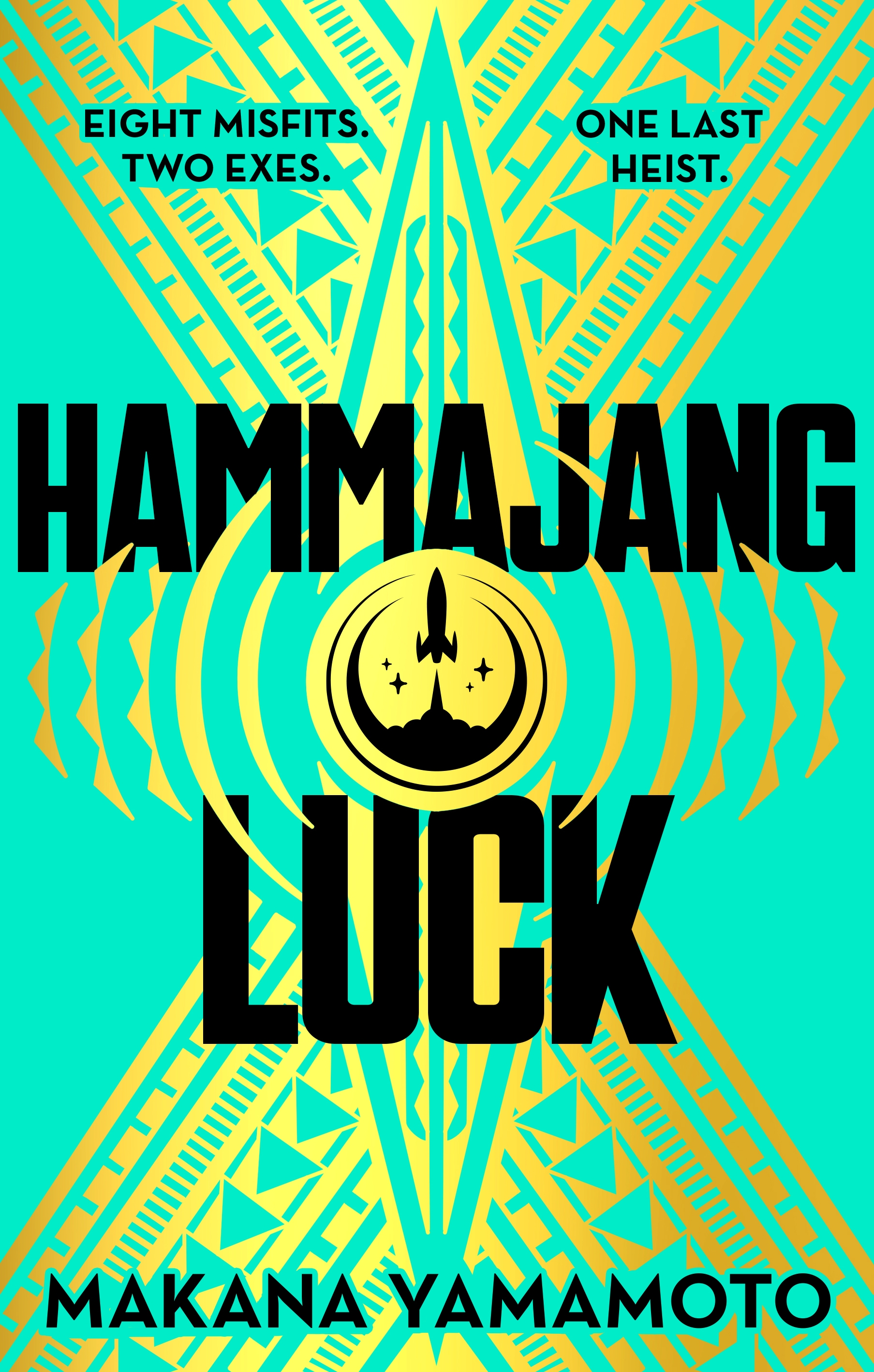

Makana Yamamoto’s SF début, a heist set on a space station, draws on the author’s Hawaiian heritage

Makana Yamamoto talks about their new novel Hammajang Luck, a science-fiction adventure set on a space station far from Earth.

“It’s ‘Ocean’s Eight’, but everybody’s a lesbian and it’s in space,” says Makana Yamamoto over video call from their home in Boston, Massachusetts, of their début novel Hammajang Luck. “That’s the joke answer. If I had to condense it down, it would be a heist novel about family, about home, culture and coming back home.”

Hammajang Luck is an incredible achievement, both a masterfully crafted science-fiction adventure and a meditation on the meaning of home. The story is a deeply political read cloaked in a heist narrative that draws attention to issues confronting contemporary Hawaii and Hawaiian culture. Only eight authors from the Pacific Islands signed a book deal last year, Yamamoto tells me, and this brings a strong desire to present a “respectful and authentic depiction” of their culture, home and family. However, it also brings pressure to be the “perfect spokesperson”.

They continued: “I had a lot of fear about it. I really wanted to do right by my community.” Début author Yamamoto is māhū, a Hawaiian term for people who embody the female and male spirit. Even if the book did not begin as a “political statement” about the Hawaiian diaspora, for Yamamoto the very act of writing is charged. “My identity is politicised. Even if I don’t want to be politicised, it’s just the nature of existing in this world as someone who is non-binary, who is māhū, who is not white, who is a lesbian. Writing about my identity is a political statement even if I don’t want it to be.”

Set on the space station of Kepler, Hammajang Luck follows Edie who has been released on parole after eight years in prison. They live in Ward Two, one of the poorer districts on the station, with their sister Andie and their two, soon to be three, nieces and nephews. Desperate to make up for lost time, Edie sets about helping Andie and looking for work, but to no avail. With limited options, they join their ex-partner in crime Angel for one last, seemingly impossible, mission—to rob tech trillionaire, Atlas Joyce. The pair begin to recruit the crème de la crème of Kepler’s underworld to carry out the heist of their lives, but can Edie trust Angel after she betrayed them?

Atlas Joyce is emblematic of parasitical Western capitalism. Described in the novel as a “tech mogul and trillionaire philanthropist”, he has built his fortune founding Atlas Industries. Yamamoto jokes that he is a “chimaera of a bunch of different billionaires” including Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and Peter Thiel. “I looked into these really wealthy, really powerful politicians, businessmen and entrepreneurs and I would find even weirder things than I was thinking I would find,” they say laughing.

Writing about my identity is a political statement even if I don’t want it to be

Atlas Industries is part of the industrial complex buying up areas of Kepler’s lower wards, ousting the inhabitants and building commercial units over domestic space. “Where did they go?”, Edie thinks, “Where could they go? So many of us had lived here for generations upon generations – there was no homeworld to go back to.” The gentrification of Kepler “is reflected in the gentrification of Hawaii and the displacement of native Hawaiians”. Yamamoto used the critical issues facing the island as “big references” for the novel. “What would it look like for the Hawaiian diaspora to be pushed out of the islands,” they ask, “and then be pushed out of the Earth and then pushed out of this space station?”

The yearning for home, both the familial and the ancestral, circulates throughout Hammajang Luck as Edie tries to re-establish communal ties and reaffirm their place in the family unit. Against the backdrop of Kepler’s mechanical environment, Edie thinks about the mountains, the sunsets and natural wonders once found on Earth. This juxtaposition was “intentional” as Yamamoto wanted to translate the tenets of Hawaiian culture, and its ties to the land, into a harsh urban landscape. “Hawaiians are very careful to preserve natural ecosystems… There’s a strong tradition of stewardship of the land in Hawaiian culture,” Yamamoto explains, and so they wanted to interrogate what it meant “to transition Hawaiian ideas and beliefs about stewardship to this technological landscape”.

The broader question of keeping culture alive in a diasporic people is deeply personal for Yamamoto. The author spent their early childhood in Hawaii and then lived on the “mainland for a couple of years”, close to their family. “With the diaspora, there is a lot of intentionality that comes into keeping ties with your culture” and Yamamoto recalls how “we would gather together, we would talk story, eat cultural food and we would dance hula”. They continued: “Similar with Kepler, we were in this place that’s so far from home [and thinking about] ‘how do we hold onto this culture that’s so important to us?’ And I think with the diaspora, it’s really finding community.”

Yamamoto uses Hawaiian pidgin—“an amalgamation of Hawaiian, English, Japanese, Chinese and Portuguese”—in much of the novel’s dialogue, particularly between Edie and their crew members. It is the “primary language” spoken on Kepler and speaks to the kinship between the characters. However, the decision to include pidgin occurred by happenstance. When writing the first line of dialogue between Edie and Cy, fellow crew member and friend, “it just came out in pidgin spontaneously”. Yamamoto “tried to rewrite it in standard English”, but it “sounded wrong”. Notably, the pidgin and Hawaiian words in the novel are not italicised or translated, nor does the novel include a glossary of terms. Yamamoto felt that these practices were “othering” and so asks the reader to do the work.

Familial bonds

Hammajang Luck celebrates familial bonds, both blood and found, and these ties take on greater significance in the wake of loss. Following their release from prison, Edie understands how much their world has changed. The family home has reorientated itself around the vacuum left by the death of their parents, one of whom died while Edie was in prison. Their personal loss is compounded by communal mourning. People have been forced from their homes and close family friends, including Angel’s father, have also died. When Yamamoto’s mother told them it was a novel “very much about loss”, it initially took them by surprise until they realised their own grief had bled onto the page.

Yamamoto’s younger brother passed away in January 2020 as they were beginning Hammajang Luck. Yamamoto takes a breath, before saying: “I didn’t even notice [the themes of loss] as I was writing. It was very subconscious. Edie coming to peace with the loss of their father, the loss of their relationship to their home, and working through that grief and getting to a better place, I think that was part of my journey too of: ‘I need to work through this sadness, anger and despair and come out at the other end and feel at peace’.”