A call to AI action

The government’s consultation on AI and copyright must inspire action from everyone in publishing.

There is no better time to pay attention to the shifts in publishing, and there is no better time to try to change the course of its future.

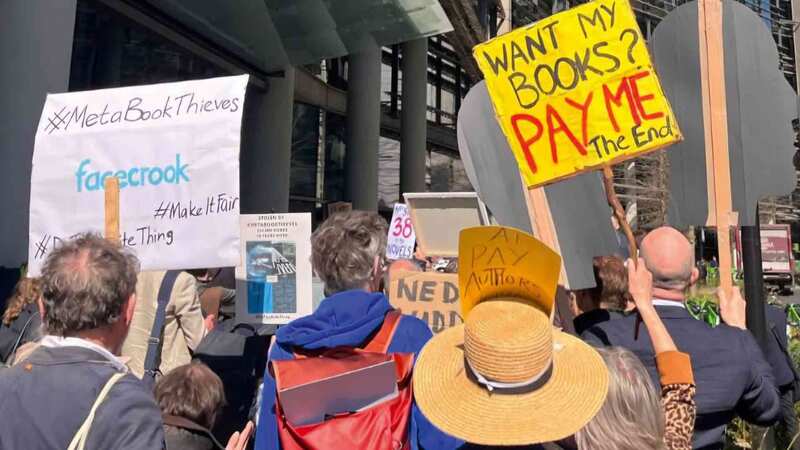

Copyright is one of the greatest issues facing writers and it will have knock-on effects for our culture, society, and economy. Currently, our outstanding creative industries contribute over £124.6bn a year to the UK economy, but people who write, publish, sing and act are seeing serious economic threats to their livelihoods because of choices and policies around generative AI.

On 17th December 2024, the UK government released a consultation on “Copyright and Artificial Intelligence”, which closes on the 25th February 2025. Although copyright sounds boring and a government consultation process inconsequential, they are anything but that.

The conversation around AI in the UK has been largely about how to use the technology to power growth. But this growth must not come at cost to the UK’s thriving creative sector. In the government’s consultation, technological innovation is prioritised over creative’s rightful control over their own work. However, there is something to be done to push back on this.

This consultation focuses on the training data used by generative AI models. The government recommends an opt-out solution to an exception on text and data mining (TDM). An exception on TDM would allow copyrighted works to be used in computational analysis, meaning an author’s work – fiction or non-fiction – would be automatically licensed for use in the training of generative AI models unless an author expressly opts out by “reserving their rights”. Of course, many authors suspect that their work has already been used as training material, and the consultation is silent on these acts of historical infringement. Instead, the consultation states that an opt-out model would be “supporting the development of world-leading AI models in the UK by ensuring wide and lawful access to high-quality data.”

There is a complete lack of clarity about how this model would work and a total lack of forethought about the downstream effects this would have on our industry and creative economy.

There is a complete lack of clarity about how this model would work and a total lack of forethought about the downstream effects this would have on our industry

For starters, there is uncertainty about whether reserved works could still be accessed and used as training data. For example, models could be trained before the opt-out is actioned, or there might be unforeseen ways to get around machine-readable reservations, or it might be difficult to reserve material from all web crawlers.

Moreover, an opt-out model places the onus on creatives, putting the responsibility onto them to know about changes and act upon them. Some authors may not realise that they need to opt-out, may not know how or why it is important to do so, or indeed, they may not be able to opt-out (for example, in the case of an estate).

As Edward Newton-Rex points out, an opt-out model can also only ever work for web domains that you personally control, meaning that downstream copies of your work cannot be effectively reserved.

In addition, regarding transparency, the government considers a high-level summary of training data from tech companies as sufficient. While tech companies might worry that anything more granular could endanger their IP, detailed summaries of training data must be called for and prioritised to ensure sufficient transparency and rightful control over creative works.

Therefore, I join my voice with numerous collectives and individuals who have warned against this proposed opt-out model. These include the ALCS and the CRA, as well as individuals such as Richard Osman, Kate Mosse, Baroness Beeban Kidron and Ed Newton-Rex. I suggest instead an opt-in licensing model – called for by the likes of the SoA and the WGGB – and a strengthening of copyright law that would place the onus on tech companies. I call for regulation on fair licensing, remuneration and fully transparent data reporting, along with the actioning of centralised enforcement mechanisms. This would not rule out the development of AI models, but it would help to give creatives rightful control over their work through ensuring informed consent.

My call to action for you is, therefore, as follows:

- Submit to the consultation: please consider reading the consultation and submitting a response, either as an individual or a collective. This can be formed as clear answers to the questions outlined, or it can be a detailed, thoughtful letter expressing your views and experience in relation to the proposal.

- Write to your MP: the Creative Rights in AI Coalition have created a template for you to write to your MP about this issue. Please consider doing so, using this template as a starting point and adding your own views and experience.

- Participate in research: my work at the University of Cambridge engages with the publishing industry to try and embed your views into this conversation. If you are interested, please email me at cic29@cam.ac.uk or sign up here. This will help to gather evidence on this important topic and will go towards protecting our industry.