You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Are editors still tastemakers?

How much influence do—and should—editors’ personal tastes have on the books they commission?

There is a certain mythology in the publishing industry about what makes a great editor. We might say that they have an "eye", an instinct or a taste that enables them to sniff out writers with potential and bring us books we really want to read. Editors can hold enormous influence: their backing can make a fledgling author’s career or launch new trends and genres.

But what an editor’s "taste" involves is difficult to pin down. It can be straightforward to suggest why a particular book does well—perhaps it speaks to a political issue or gives voice to a previously overlooked perspective—but, looking at the careers of editors who work on a wide array of books, it is tricky to identify the ingredient of their success. Of course, the fate of a book does not sit with editors alone: publicity and marketing departments hold ever more sway. We must ask, however, what the role of an editor’s taste might be, and whether it still has currency.

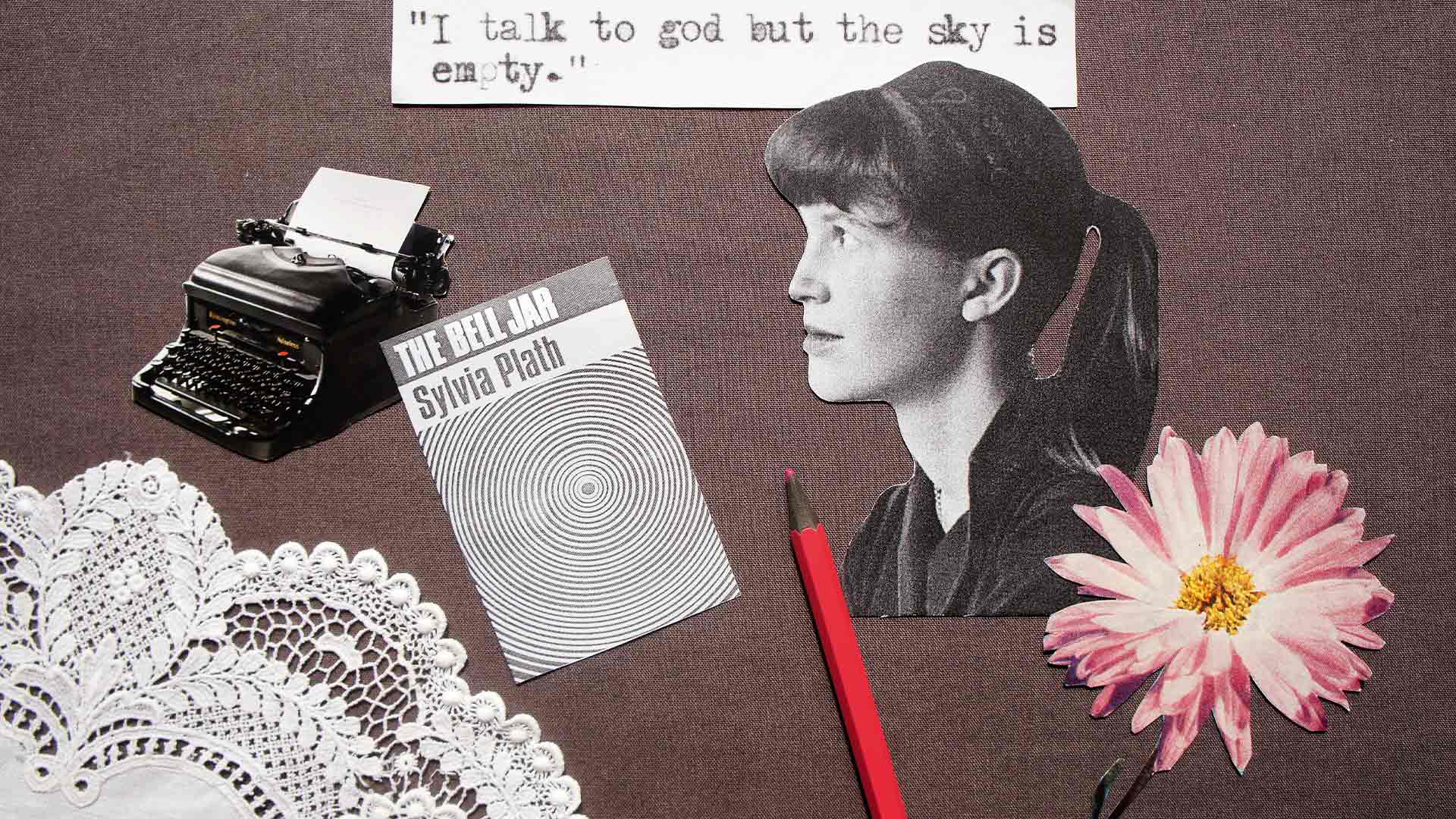

In The Editor: How Publishing Legend Judith Jones Shaped Culture in America (Atria Books), Sara B Franklin offers a portrait of an archetypal "taste-making" editor. Judith Jones’ decades-long career began at Doubleday before she moved to Knopf, where she rose through the company’s ranks to become vice-president. Jones championed writers such as Sylvia Plath and John Updike, as well as persuading her boss to publish the English translation of Anne Frank’s diary in 1949. She also (perhaps most famously) launched a whole wave of cookery book authors, from Julia Child to Joan Nathan, helping to transform the form from a dusty "women’s genre" to the enormously lucrative area of publishing it is today. Jones used her own interests as a guiding principle and was a keen amateur cook who went on to write her own recipe books. She had a great deal of confidence in her own judgement and published books that she herself wanted to read.

There are details in Franklin’s biography—the handwritten exchanges between the editor and her authors, and the green pencil with which Jones would mark up manuscripts—that point towards a bygone era. And it is clear that Jones’ taste was informed by the time she lived in. Franklin acknowledges that Jones’ commitment to her personal taste led to what we would now identify as oversights and even narrow-mindedness: she passed over Plath’s The Bell Jar since she "was not at all prepared as a reader to accept" the novel’s stark evocation of a mental health crisis (as she put it in a letter to Plath). Jones assumed that readers would share her perspective. She encouraged the cookbook author Madhur Jaffrey to prioritise recipes which would not be "too surprising to the palate", believing that a single type of reader would buy her book.

More and more, the editors having the most impact on the publishing landscape are those with a defined cause, set of ideas or guiding principle that informs their decision-making when commissioning and acquiring titles

This is not to say that making editorial decisions informed by one’s own perspective is always misguided. Jones’ distinctive taste led her to champion books that might have otherwise been overlooked: Anne Frank’s diary is the most striking example, but she also helped forge the reputations of an array of authors, including Langston Hughes and Anne Tyler, through her sheer enthusiasm for the quality of their writing. Indeed, identifying books that they themselves want to read remains a crucial aspect of an editor’s toolkit. Editors shape trends according to their priorities and those of the culture they live in. Speaking recently on the New York Times’ "The Book Review Podcast", Simon & Schuster president Jonathan Karp declared that one of his longstanding editors, Marysue Rucci (who now leads an eponymous imprint within S&S), has "just got it" as an editor, with "it" being intuition about which books have "that quality" that will attract readers.

The taste of an esteemed editor, it is clear, is still a prized currency at many publishing houses. The runaway success of the independent publisher Fitzcarraldo Editions, founded in 2014 by Jacques Testard, stems in large part from its association with the flawless taste of Testard and his editors (this taste holds influence in high places: four of Fitzcarraldo’s authors have gone on to win the Nobel Prize in Literature). However, in an age of increased competition for market share, some publishers are encouraging their editors to define their trademark beyond simply having a "nose for quality".

More and more, the editors having the most impact on the publishing landscape are those with a defined cause, set of ideas or guiding principle that informs their decision-making when commissioning and acquiring titles. For example, Romilly Morgan, who launched Brazen Books in 2022, has become renowned for publishing feminist books that shake up tired stereotypes. For Morgan, "the great publishers out there are defined by their distinctive tastes… tastes that don’t toe the line, that aren’t conformist to publishing past and that really, clearly voice the moment".

Nevertheless, an editor’s job remains closer to that of a stage manager than a performer, and some publishers maintain that their role should be largely behind the scenes. For Helen Wicks, managing director of children’s trade at Bonnier Books, editors should aim "not so much to be ’tastemakers’, as… to empower our readers to form their own tastes". Sarah Benton, also a managing director at Bonnier, reflects that, as an editor, "what I personally love" and "what I think readers will love… are often not the same and that is how it should be". For Benton, the imperative is to "balance commercial awareness with editorial instinct" and thereby "lead the market, not follow it".

This editorial instinct must not be undervalued. Readers today are spoilt for choice, and by curating a list with personality, editors generate momentum for titles that might otherwise be overlooked. Ultimately, though, as Franklin concludes in her biography of Jones, it is "never really about [the editor] at all". The best editors cultivate books that can sing on their own.