You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

The battle for B&N

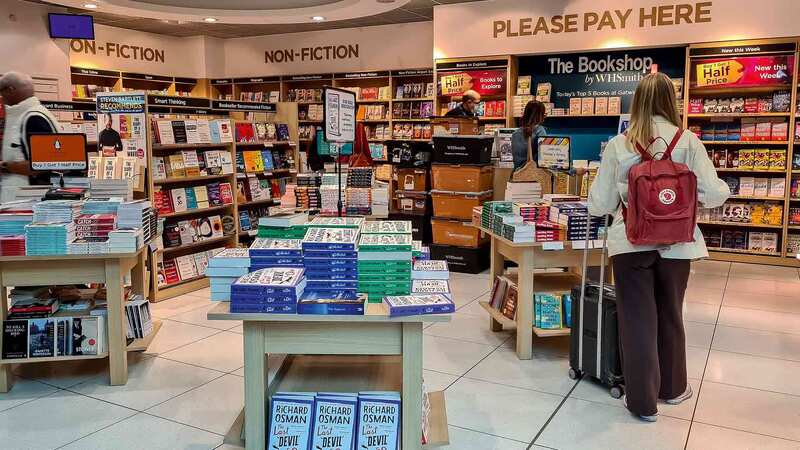

The fight to acquire US bookseller Barnes & Noble (B&N) is a battle for the future of the book business, a wrestling match between the old-school bookselling charm of James Daunt and the data-led machine of the giant distributor Readerlink. Both might succeed; both will change publishing. The alternatives are worse.

If Daunt wins, backed by the monied Elliott Advisors (UK), then B&N will be run as Waterstones is: as a chain of locally oriented faux-indies, curated by knowledgeable staff, but backed by a controlling head office. It will result in independently minded booksellers, driven (as I wrote late last week, when news of Elliott’s bid for B&N leaked in the Wall Street Journal) by the performance of their own stores, not the needs of suppliers. Readerlink represents a different model. As the largest US book distributor to non-trade outlets, it uses analytics to stock and refill shelves in non-specialist stores that want, but do not know how to run, a book offer. Played out across the 627 dedicated B&N stores, this approach could revolutionise the trade, offering, perhaps for the first time, a “big-tech” counter to Amazon.

For publishers, as this week’s Lead Story suggests, there is no easy answer. Both approaches will want improved terms; both will take time to bed in. As a private company Readerlink offers a long-term home, albeit without access to the funds Elliott has; Elliott offers a shorter-term solution, and is reliant on Daunt to juggle a transatlantic role that few can sustain. If, as agent Mark Gottlieb writes this week, US publishing is too much in thrall to “the numbers”, then Readerlink could exacerbate what is already a chronic problem for agents and writers: data-driven uniformity that offers readers only more of what they have already bought.

Yet if it comes down to a choice between the head or the heart, there will be some publishers—chiefly among the corporates—who will choose the former.

For the UK book trade there are mixed emotions, too. Daunt is now much admired across this business, but as he himself admitted just two months ago, Waterstones’ own future is not yet secure. It remains reliant on its parent/funder, just as it was when Alexander Mamut rescued it back in 2011. If the end goal is to float the business, the value of adding $3.7bn (£2.9bn) in sales for the knock-down price of $683m (£540m) is obviously attractive. In total, Elliott will have put a value on the two businesses of $960m (£750m), just a fifth of their combined turnover—compare that to W H Smith, whose market cap is a generous two-times sales. Yet given even this context, there is no certainty of reward. Amazon, whose book businesses continue to grow (as Rome burns) will hardly be quaking—as the ongoing travails of Philip Green’s retail empire indicate, the high street remains stricken, any treatment more analgesic than cure.

Wherever you sit in this business, what began as a big punt for Daunt, Elliott and B&N has become a massive crossroads for us all, a sliding-doors moment for the high street bookshop.