Beyond the hero's journey

If we are to escape toxic Western attitudes, we need new models of storytelling.

What kind of stories do we need to save the planet? That question has been on my mind again in the wake of the news that last Monday world temperatures reached the hottest levels ever recorded. Many of us know the implications of the trajectory we’re on in terms of climate change — scientific consensus is now that we are heading for 2.5 degrees of global warming, which will bring with it “catastrophic consequences for humanity and the planet”. For writers and artists, the magnitude of the challenge we are facing can sometimes seem far too vast for the creative tools we have to hand. Yet there is a powerful connection between how we choose to live as a society, and the stories that society tells itself.

For far too long, the prevailing narrative structure dominating fiction, films and theatre in English-speaking cultures has been the "monomyth": a plot in which a hero sets off alone on an adventure, overcoming seemingly insurmountable odds to win a decisive victory. Famously outlined by Joseph Campbell in his 1949 book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, the monomyth has had an astonishing impact on popular culture and a ubiquitous imprint on Hollywood movies, from "Star Wars" to "The Matrix". No doubt most writers who have undertaken creative writing courses have been taught, at some point, a version of Campbell’s assertion that the monomyth is universal.

In How to Tell a Story to Save the World, writer and environmental activist Toby Litt argues that this centring of individual heroism in the stories told in English-speaking cultures has bolstered the capitalism that drives them. Capitalism, after all, is itself a story of the good of individualism and "rational self-interest", which drives unchecked growth. Within capitalism, each of us is the hero of our own narrative, fighting for victories defined only on our own terms.

But, as we now know, capitalism and the overconsumption it validates are the forces pushing our planet to the brink of destruction. Litt argues that the centrality of the monomyth and the writing gurus who have promoted it bear a heavy responsibility for the ecological mess we now find ourselves in, because they have created “the people who are capable of destroying the ecosystem, and who are selfish, irresponsible, exploitative and completely incapable of seeing why they should be otherwise, because they have seen, again and again, that only the Hero is guaranteed to survive — only the Hero counts”.

If we want to survive in a liveable future, we need to consider, deeply, not only what kind of stories we tell, but how we tell them

Yet there are other kinds of stories. Many Indigenous cultures around the world have their own storytelling traditions that stand in stark contrast to those in English-speaking cultures and which exist in dialogue with the particular relationships held by those communities to one another and the land they inhabit. In Bolivia, the Indigenous Quechua and Aymara communities tell stories through the journey of the collective, not the individual. The Kwik-Kwak of the Caribbean centres call and response between audience and teller, a process that unsettles the ownership of the story’s narrative. In the animism of ancient Celtic legends, animals, plants, rocks, the wind and the water are charged with spirits, undermining the dominance of humans. Native American tales may not have a beginning or end — a character’s journey spanning a constellation of interlinking narratives understood only by those who are part of the community.

In May, the Australian author Alexis Wright won the Stella Prize, Australia’s biggest literary prize, for her novel Praiseworthy. An epic, time-bending, multi-narrative novel about the climate emergency and its impact on one Aboriginal community, the award makes Wright the first person to win the Stella Prize twice, after Tracker in 2018, marking her as one of the most important authors in the world today.

Beyond the obvious wit, beauty and inventiveness of her prose, what makes Wright’s books so urgent is the fact they are the inheritance of a different cultural legacy to that which has dominated the English-speaking publishing sector. Wright is a member of the Waanyi Nation, and her stories are rich in the narrative forms she was raised with: the "songlines" in which story is told on the move and connected to the land; "The Everywhen" (a temporal sensibility quite unlike the linear history familiar to Eurocentric cultures, where events pile up at greater and greater distance as they stretch back into the murky reaches of the past). Instead, this is a sense of the continuous present: events that have happened are still happening; our ancestors, like our descendants, are with us in the now. In Tracker, Wright creates a polyphonic biography of Aboriginal activist Tracker Tilmouth, drawing on Aboriginal storytelling tradition to weave together many voices in a portrait of Tilmouth: “A reasonable response to a lifetime of our stories being told and misrepresented by others”, she writes.

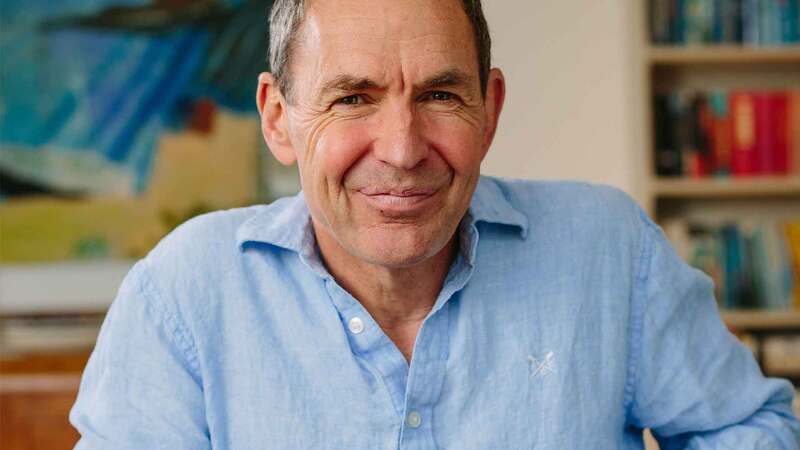

I interviewed Wright for my recent book, Acts of Resistance, which focuses on the power of art to create a better world. She has a great faith in literature as we face a troubled horizon: “It will be literature,” she believes, “that is capable of offering more thoughtful scope, and far more imaginative possibilities. That will have the capability of transmitting knowledge to expand our understanding of how to think about the realities of our future times”.

Perhaps the literary world’s readiness to embrace Wright’s work signals a growing awareness that if we want to survive in a liveable future, we need to consider, deeply, not only what kind of stories we tell, but how we tell them. It’s time for those of us in capitalist societies to set aside our worn-out stories of heroism and to ask ourselves: what paradigms do we need to enable us to make the imaginative leap into the society we want to inhabit? Narratives like Wright’s invite us to understand ourselves primarily as part of a community, not only with our peers but with our ancestors and descendants too; to engage with the environment as vividly as any human protagonist. “We’re entering the most challenging part of our times on earth,” Wright told me. “It’s time to write the big epics of what’s happening around us, and to do it in a way that people will read it.”