You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

The book trade must beware lipstick feminism

When browsing in a bookshops nowadays, you’re likely to find a carefully-curated stand of ‘Feminist Literature’, ‘Women’s Writing’, or ‘Rebel Reads’. An empowering and exciting sight to see, given the past politics of female written literature being given space on the shelves. However, do we give much thought to how these books are marketed, or how they are placed in the hands of those reading them? What makes a book, a bookseller, a brand, or a platform ‘feminist’, and why? In an age of ever-present advertising and branding, of conscious consumption and being woke, we should take it upon ourselves to ask the question: is it feminist, or is it capitalist – lipstick feminism, in other words?

Lipstick feminism can be defined as the use of ‘feminism’ as a buzzword to make sales, attract potential consumers, or to labour a false incentive. The performative use of the word by a marketing, advertising or brand campaign, without wholesome values and ethics behind it, is mere capitalism, and a masquerade of something consumers may be buying into with good intentions without realising the hollowness at its heart.

One example is the recent scandal around Topshop and Penguin’s anthology, Feminists Don’t Wear Pink and Other Lies. Penguin had collaborated with the women’s clothing store in London to operate a pop-up shop themed around the anthology’s release, a book whose profits have been donated to UN charity, Girl Up. What was positioned as a promising collaboration, and an exciting opportunity to put an attractive, digestible anthology of feminist essays by writers and celebrities alike in front of young, impressionable women, was dashed only minutes before it was set to open to the public.

Topshop called for the installation to be closed down before the doors opened, leaving anthology curator, Scarlett Curtis, to remark her disappointment on Twitter and state that “the patriarchy is still alive and kicking”, whilst sharing the hashtag #PinkNotGreen as a statement against the Topshop c.e.o., Philip Green. Her statement, coupled with the deliberate silencing of a genuine feminist narrative, exposed Topshop’s motives when it came to selling and manufacturing ‘feminist’ slogan clothing. It highlighted an intent to make money from a buzzword which has most likely been seen as increasing in popularity with their audience, added to clothing lines as a ‘trend’ piece, but with no motive behind it to support feminist causes like the anthology and Girl Up.

In this example, genuine feminist publishing was confounded by an unfortunate partnership. But how is lipstick feminism perpetuated within publishing? Lipstick feminism in the publishing industry is especially damaging in an age where we’re trying to actively dismantle the patriarchal dominance and bravado of male authors and create an inclusive, diverse space for everyone. There are too many examples to name of marketing aimed at a female readership that include exclusive use of images of white, skinny women reading, as well as bookselling or promotions coupled with free beauty products. Used in moderation, in the right context, or alongside other diverse images, these are effective advertisements, or lovely gifts. However, when used as a core brand image or promotional material alongside the promise of ‘feminism’, they largely play into a narrative that upholds stereotypes of femininity born from patriarchal ideals.

If a marketing campaign relies on representing ideals already perpetuated in society like thinness, impossible beauty standards, ableism, heteronormativity, cisgenderism, and whiteness, it’s not feminist; it’s misogyny, and it’s degrading and offensive. Brands, campaigns and bloggers alike have a duty to fully represent their audience in the pictures they use, and also look beyond the “what a girl wants” mindset when constructing press releases, PR goodie bags, and online content.

Social media is key here too. Something that happens quite often in the realms of social media are giveaways scheduled around important awareness days, such as International Women’s Day. A stack of themed books, slogan merchandise and the like often circulate around trending hashtags, and whilst it arguably can remind people of an event they may have not been aware of in a fun way, if a publisher or bookseller only speaks up about these causes once a year in the designated day/week/month, then it looks like simple tokenism. Are they speaking out throughout the year on these issues, donating to relevant causes and refusing to publish known misogynists? And are their ‘feminist reads’ – or those they promote from bookstagrammers – coming from a very narrow selection of women, in terms of their race, size, religion and age?

You might ask why lipstick feminism needs to be avoided or indeed actively contested. Brands, advertising and marketing can be disingenuous at the best of times in pursuit of profit, so why is this different? In recent years, there’s been a real pull of focus towards women’s issues, ending gender parity, starting involved conversations on diversity, genuine representation in media, and amongst this, a growing interest in feminism and what it means for people in the 21st century. To sell a shelf of all-white female authors, say, to an ambitious young feminist does not set them up for success in the inclusive, diverse journey they deserve. Moreover, people need to see themselves represented within the media and the feminist narrative at large. This means representation of BAME women, disabled women, women of all sizes and appearances, LGBTQ+ couples, non-binary persons, and more. If something is being sold as ‘feminist’, and does not represent a broad range of people, then it’s false advertising.

A clear example of a feminist organisation doing it right is the Women’s Prize for Fiction. The organisation doesn’t just showcase diverse female writing - it celebrate its in a way that includes no disingenuous brand endorsements, questionable advertising, or whitewashed display of book titles. The organisation shows up again and again when it comes to intersectionality and representation; including a trans, non-binary writer in their 2019 longlist. Ultimately, other brands can follow suit by making conscious decisions about who they represent and how they do so, and being candid about supporting feminist causes that matter.

This doesn’t mean, however, that lipstick feminism should become part of cancel culture. Unless a brand, a person or an organisation is doing something hugely problematic and damaging, we can politely point out where they can do better, rather than scythe them down. Simply checking in with a publisher, bookseller or blogger and asking questions about the content they’re putting out in the name of ‘feminism’, and holding them to account, means that we can work towards a more purposeful, and more impactful meaning of the word - in the publishing world and beyond.

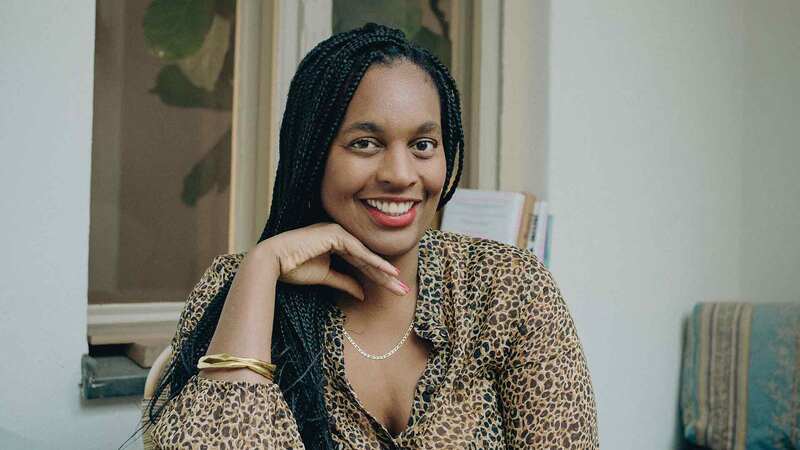

Molly Masters is the founder and c.e.o. behind Books That Matter, the book subscription box service championing diverse, female-led fiction to empower and inspire readers. She also writes academically on feminist dystopian fiction and reproductive rights, with a passion for intersectional feminist literature.