Bookshop politics

We need more discussion about bookshop bias.

Hundreds of books are published each year across the publishing landscape that examine world politics and history through nuanced lenses, but on-ground strategies for marketing books can diminish these efforts towards global community-building and representativeness, or reduce them to token representations that continue to uphold existing biases, especially against countries that belong to the Global South. In a sense, your local bookshop is probably a good mirror of the political unconsciousness of your country.

A historical bias?

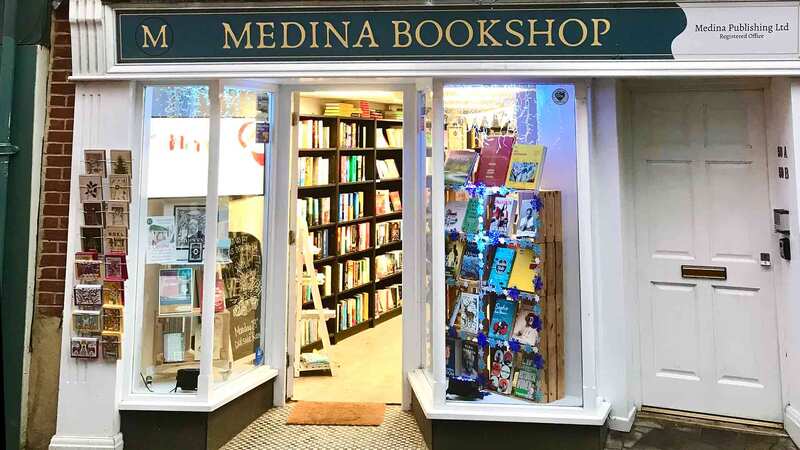

While pursuing my master’s degree this year, I worked part-time at a bookshop in Oxford. I’ve always been interested in the publishing industry; with this job, I was eager to learn about marketing strategies used by booksellers that buttress the publishing sector and inform the success of books in very material ways. Marketing in the shop took many different forms; commercial managers liaising with publishing houses identified the "next big books" which were signposted and highlighted through the shop; posters would point readers towards them, big-name author reviews were blown up on signboards; booksellers were briefed about talking these books up; crucial to the shop I worked at, recommendation cards were prepared and interspersed throughout shop sections, so that browsers could be gently nudged towards these bulk order books. The success of these books is guaranteed through dozens of small but meaningful strategies.

I often worked the till in the history and politics section of the shop, and was looped into these marketing strategies for this section; I wrote cue cards and rearranged shelves to signpost readers towards books the publishing industry wanted to turn into bestsellers. It was here that I stumbled on an uncomfortable realisation: these sections, which claimed to cater to "local reader preferences", consistently reinforced existing biases against postcolonial countries of the Global South. Whether this bias is conscious or unconscious, once recognised, it was impossible to unsee.

The history section of the shop was an exercise in colonial liberalism: British history makes some space on its shelves for Asian and African ones, but unconsciously reinforces antiquated imperial beliefs.

Six shelves lie between Edward Said’s Orientalism and Stuart Laycock’s All the Countries We’ve Ever Invaded: And the Few We Never Got Round To. During my first week at the shop, the manager in charge of the orientation pointed to Laycock’s books and turned to us, five newbie booksellers: “Pop quiz, how many countries have we invaded?” They looked at each other, shrugging and laughing. One of them chimed in, “Wasn’t it like, all of them?” I was the only person of colour in that group; I could tell you the number in my sleep—173. The pervasive seepage of colonial mentality into contemporary life is stark, even shocking. The recommendation card for the book took a line off its Amazon review: "We’re a stroppy, dynamic, irrepressible nation and this is how we changed the world, often when it didn’t ask to be changed!’ The colonial enterprise that nearly destroyed half the world can be turned into a pop quiz you don’t even need to know the answer to.

Marketing to a racialised audience

The gap between representation in the publishing industry and marketing on-ground can radically alter the narrative effect of a publication itself. As a South Asian, my familiarity with South Asian literature meant I could identify changes made in books published in India and in Britain. Objective marketing changes are made at the publishing level: William Dalrymple’s The Anarchy is subtitled "The East India Company, Corporate Violence and the Pillage of an Empire" in India, but the UK edition calls it "The Relentless Rise of the East India Company". Shashi Tharoor’s Indian edition of Era of Darkness made it across the ocean as Inglorious Empire. Two versions of each of these books market two narrative tangents to racialised audiences, without changing a single word of content; it impacts the perceived "dialogue" between postcolonial and coloniser nations as layperson readers continue to hold colonial biases encouraged by such narrative shifts.

But some sections are eternally stagnant; the Middle Eastern section titularly represents narratives of terror and violence that do not contextualise the role of neocolonialism, oil capitalism and Islamophobia

Within the bookshop, narrative shifts are visible with shifts in geopolitics; since the start of the Russia-Ukraine War, the number of books on the cult of Putin has increased, as have books documenting Ukranian struggles during this period. But some sections are eternally stagnant; the Middle Eastern section titularly represents narratives of terror and violence that do not contextualise the role of neocolonialism, oil capitalism and Islamophobia. Books on Afghanistan purely engage with "heroic" American and Soviet war efforts; the fall of Reza Shah Pahlavi and the rise of Ayatollah Khomeini’s Islamic Republic of Iran is a two-shelf spread that hides a slim volume of Faisal Devji’s Islam after Liberalism, a critical collection that assesses the compatibility between Islam and Western political thought— the Middle East is only of interest when it portrays Islamic "backwardness".

Once I was cornered by a woman who said— “Show me the books on jihad. On terrorism. On Islam.” When I stared at her, completely taken aback, she turned impatiently to my colleague, who simply pointed her to Middle Eastern History.

A possible solution

Marketing strategies can undo what research and extensive efforts towards global community building and better representation have sought to accomplish. Unfortunately, buying into biases and re-creating modes of historical thought can be extremely lucrative. But subversion must not be limited to writing alone. If we’re attempting to change the the political unconscious of a global community through writing, strategies at every level of the publishing industry must be considered, because it is an effort to fundamentally alter the historical perceptions coloniser nations have about countries from the Global South.

Bookshelves create and solidify perceptions that could potentially be harmful. We must ensure that balanced viewpoints are presented to readers so that they can evaluate and formulate unbiased opinions on nations, especially those which have been historically subjugated.