You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Censorship creep

The UK, like many other parts of the world, has a long history of banning books for "obscenity". The last time it happened in the UK, at least officially, was in 1990, when Lord Horror by David Britton was censored up until 1992. But if "obscenity" was the main reason for censorship before, today things have become more complicated. Now we preach censorship based on disagreement of opinion and the imputation of imaginary crimes. In a way, modern versions of good old obscenity.

And censorship does not end when a specific work ceases to be published or is prevented from circulating, but is directed at the author in an attempt to promote the cancellation of any work already published or even to be published in the future. The UK and the United States are at the forefront of this new method, such as in the cases of JK Rowling, Woody Allen or Jordan Peterson. What these very different authors have in common is that they have fallen foul of popular outcry against what is considered obscenity in our modern times.

Freedom of expression is sacred even when we don't like the content of a book or its author - unless, obviously, we are speaking about someone openly preaching to exterminate a group. Sure, there are limits to freedom of expression, but we definitely cannot draw the line on opinions with which we disagree.

Even though marginalised groups might have a point when, for instance, criticising some authors and the content of some books, the result is not far from the same censorship that conservative groups have historically tried to impose – censorship that often backfires.

In Brazil, censorship against books is not uncommon, especially biographies, but now a new method has emerged: that of combating perceived obscenities by attempting to destroy the author's life. Until 2015, any biography could be censored if the biographed person did not agree with its content and decided not to authorise its publication, which virtually prevented the publication of any unauthorised biography. That year, the Supreme Court decided to suspend the requirement for prior authorisation, a real leap forward.

But the decision did not put an end to censorship of books and even comic books, as was the case with the government of the state of Rondônia, which created a list of books to be collected from schools. The governor of the state is a far-right conservative close to Brazil’s president Jair Bolsonaro, considered by many a fascist. Also in Rio de Janeiro, where the mayor, a religious fundamentalist, ordered the censorship of a comic book with a LGBT-friendly theme during the city’s Bienal do Livro, an annual book festival.

In Rondônia, the governor backed down after the backlash. In Rio de Janeiro as the mayor decided not to give up his crusade in "defence of the family," YouTuber Felipe Neto, with millions of followers, decided to buy all the LGBT-friendly books and comic books available at the festival (about 14,000) and distribute them for free.

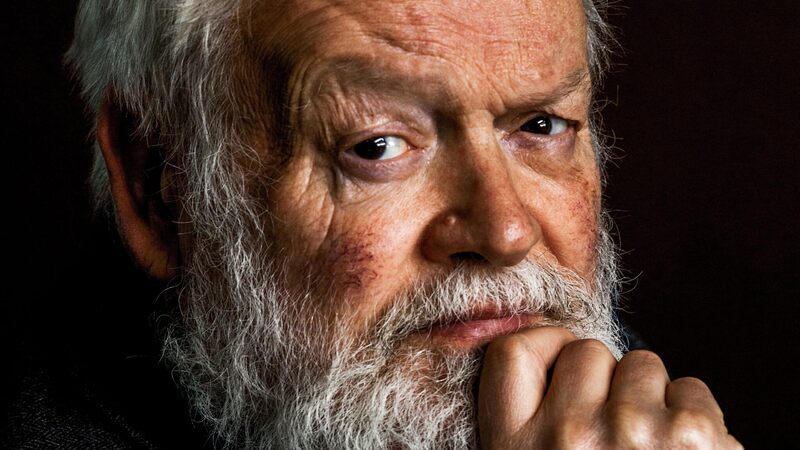

But another recent case comes to mind, that of João Paulo Cuenca. Even though the methods are different from previous attempts of censorship, in common is a shared view of what constitues an obscenity, and extreme action to shut down a controversial opinion that some do not like.

Cuenca is being sued by dozens of fundamentalist pastors of the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God for a tweet in which he criticizes the evangelical sect using a famous phrase written by Frenchman Jean Meslier. This is the same church of the former mayor of Rio de Janeiro who tried to censor the comic book. The censorship here, like with other cases in the UK, is not even directed to a particular book, but against the author’s personal views and comments.

"[The] Brazilian will only be free when the last Bolsonaro is hanged from the guts of the last pastor of the Universal Church,” said Cuenca in a tweet – later deleted. He tried, in a Twitter thread, to

Já expliquei o óbvio e o faço de novo: atualizei, com fins de sátira, uma frase do século XVIII bem conhecida e atribuída aos iluministas Voltaire e Diderot, mas escrita pelo abade francês Jean Meslier. Essa frase, originalmente sobre reis e padres, teve diversas encarnações. 4/

— J.P. Cuenca (@jpcuenca) June 18, 2020

His phrase may be criticised, but the author was

Já expliquei o óbvio e o faço de novo: atualizei, com fins de sátira, uma frase do século XVIII bem conhecida e atribuída aos iluministas Voltaire e Diderot, mas escrita pelo abade francês Jean Meslier. Essa frase, originalmente sobre reis e padres, teve diversas encarnações. 4/

— J.P. Cuenca (@jpcuenca) June 18, 2020

What we are witnessing are new methods of censorship, but with the same old excuses - not conforming to what is perceived as "good", whether that be the mainstream view of society, or the consensus of specific groups who hold sway in a given moment.

As the cases above show, those who have the power end up being able to impose censorship and silence those who oppose them. It makes no sense to enter the same game and try to silence those we disagree with. It doesn’t matter if you believe you’re on the right side of history, once you preach censorship there’s no turning back - and the consequences will not be restricted to your perceived enemy.

Raphael Tsavkko Garcia is a Brazilian journalist published by Al Jazeera, DW, MIT Tech Review and Tor, among other news outlets. He also has a PhD in Human Rights.