You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

The way forward

Libraries and publishers have much to gain by taking a more collaborative approach in the way they work with each other

Books and e-lending are big business for libraries. Pre-pandemic, public libraries supported an estimated 165 million physical loans per annum, with many millions more across schools, universities and the health sector.

The pandemic created a surge in e-reading. Library charity Libraries Connected reported increases in e-book loans during the pandemic of 205%. Newly updated figures show that e-lending has remained at significantly increased levels even as lockdown restrictions have eased.

At the height of the pandemic, many publishers and platforms stepped up to support this sudden transition, relaxing licensing restrictions and enabling platforms to adopt multi-user models to permit simultaneous e-lending.

But as we emerge from the public health crisis, publishers and libraries don’t necessarily see eye-to-eye on how to accommodate this new demand for e-reading and digital engagement in the future.

Some publishers and retailers see library lending, and particularly e-book lending, as a direct attack on sales. For our part, librarians (notably through the eBookSOS campaign) have highlighted unfair pricing, restrictive licensing terms and the “bundling” of useful and less useful content into costly packages (which can then disappear without warning) as an assault on our ability to fulfil our educational role on behalf of our users.

Brave new world

It is important to acknowledge that these changes are taking place against the backdrop of an ongoing process of digital disruption.

I believe publishers and libraries need to work together to navigate this new environment for the benefit of the book-buying and reading public. This takes time, empathy, mutual respect and good faith.

In the process, I believe there are some key emerging themes around which we are all strongly united.

It has been a real positive of recent years to see the efforts of publishers, authors, booksellers and librarians to make meaningful progress towards a more diverse and inclusive book trade, even if there is so much more still to do.

Similarly, the emerging impetus towards a more environmentally accountable and sustainable book trade is something we all hold in common, and which demands a collective response from libraries and publishers alike.

I believe we also have a common interest in protecting and promoting the UK’s extraordinary fund of talented authors, researchers, illustrators and editors, without whom neither librarians nor publishers could function.

Most of all, we share a common commitment to reading and readership, the health of which benefits us all.

The business case for library lending

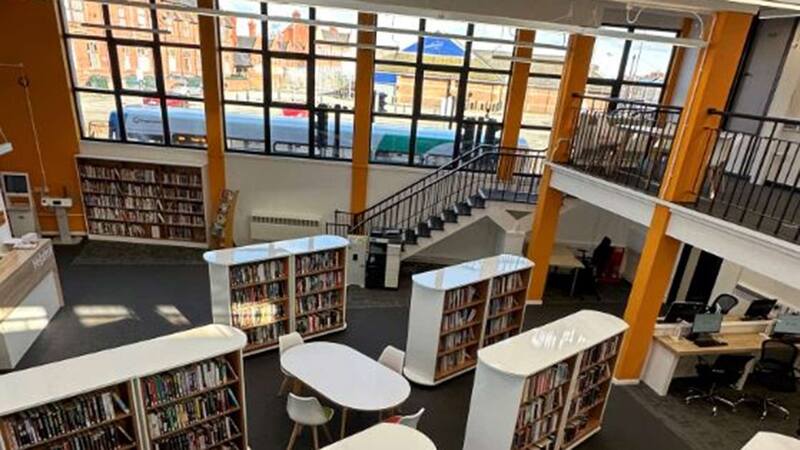

I think it is important to challenge the “deficit model” of library use, which holds that libraries exist primarily to loan books to people who could not otherwise afford to buy them.

This is, of course, a vital function of libraries, but it is not why libraries exist. The point of a library (and particularly a public library) is to promote education and universal access to knowledge, information and reading irrespective of a person’s means.

Librarians value and appreciate the affection and goodwill we receive from the book trade, but we also need to be clear that there is a hard-nosed business case for publishers to work with us to find more effective solutions to library lending and e-lending.

As the publishing industry navigates an era of digital disruption, a more permissive and collaborative approach to library e-lending would be a smart investment in building and sustaining the market for books and e-books.

This is more complex than the old “borrowers are also buyers” argument (although it is undoubtedly true that a reader is a reader, and likely to do both). Libraries have a deep insight into readership, hyper-local and emerging trends, and shifts in consumer demand. We experience at the frontline the changing interests of readers, which will ultimately determine whether a book is successful or not.

In this sense, a stronger collaboration between publishers and libraries could yield some very significant business benefits. Publishing is a risky business. Imagine if we could work together to de-risk the publishing pipeline, to aggregate and share data on real, grassroots readership, to make it easier to predict demand, to improve metadata and discoverability or even to start to erode the bête noire of all publishers—returns.

If publishers can work with the library community to find ways to allow us to do our core job—which is not to give books away for free, but to use them as a tool to inspire the readers, authors, creators and learners that ultimately constitute both the raw material and the future market for the publishing industry—there is the potential for a much more sophisticated and nuanced relationship which plays to our respective strengths.

It is this spirit of collaboration based on a better and more contemporary understanding of the different but complementary roles of libraries and publishers that I hope emerges in the next few years. We have nothing to lose by finding better ways to work together, and everything to gain.

Nick Poole is the chief executive of Chartered Institute of Library & Information Professionals