You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

A crying shame

In one of the less starkly memorable scenes in Irvine Welsh's Trainspotting, protagonist Renton evades incarceration after delivering an impassioned, eloquent speech in which he claims he stole books in order to read them, and by extension, better himself. He does so in 'perfect' English, not the curse-splattered Edinburgh dialect the novel is renowned for, and his judges are lenient. His co-conspirator, Spud (“spot on man...eh...ye goat it...ah mean...nae hassle likesay”) is not so fortunate.

Renton is able to code-switch, to adapt his language to his surroundings. Leaving the court, he confides in the reader that he has pulled off 'a stunning coup de maitre', peacocking into a third tongue to underline his proficiency. The scene springs to mind in light of Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year choice, the 'crying-with-laughter' emoji. Detractors of the decision (there appear to be many) seem to focus on two points: first, that it is not a 'word'; second, that it epitomises a dumbing-down of culture, an idiocy among the yoof that heralds the end of graces, manners, civilised society as we know it.

To do so is to miss the point.

The emoji in question was selected, Oxford writes, because it is the most widely used among the icon language's repertoire. The 'crying-with-laugher’ emoji accounts for one in five emojis used in the UK, it claims. Who knew us Brits had such humour? It is not a 'word' in the strictest sense, but under such scrutiny nor are four of the eight shortlisted alternatives ('sharing economy', 'on fleek', 'ad blocker', 'dark web'). Also on offer is a compound word ('lumbersexual') and a pretty unsightly, mongrel noun (‘Brexit'). These 'words' were chosen, surely, not because of their adherence to a formula but the opposite; their ability to capture a cultural zeitgeist, to slither into the public consciousness because of their refreshing uniqueness.

Perhaps picking ‘emoji’ itself would have incited less animosity. An emoji is, more accurately, a kind of modern-day heiroglyph; some may prefer to think of it as a typographic ornament of sorts. Its choice as Word of the Year may have raised ire because it appears deliberately provocative (read “shareable”, though there are worse crimes, one feels, than a centuries-old institution with a somewhat fusty reputation attempting to widen its reach - especially beyond its usual parameters) to some, but emojis' ubiquitousness is not in question. In terms of conveying a particular emotion (or object) with concision, they can be unrivalled, exorcising the middleman between Saussure’s signified and signifier, creating, in one sense, the pure method of information transmission that many Modernists - Gertrude Stein and Ezra Pound chief among them - strove to create. Language can be ‘like a window pane’, Orwell famously wrote, but it can obfuscate, too.

Add to this the fact that our methods of communication are inextricably linked to our means of communication. We prefer to look back on wartime telegram-writers, smattering their messages with STOPs and acronyms, with a gleeful nostalgia, rather than to denounce their linguistic abominations. Ditto Egyptians and their heiroglyphs. Who is to say, given the transcultural, multilingual modern world, that a universal mode of communication is not, in fact, a superior mode of communication?

To suggest its selection represents the youth misled also appears to be erroneous. For starters, emojis are arguably equally prevalent among the 'educated' (in both regards, i.e. post-education and well-educated); to believe they are wholly the language of the young is false. One suspects this perception abounds because emojis are solely the preserve of the technological realm, rendered only in pixels - although some luddites persist with the semi-colon-and-close-bracket-symbol. Yet previous Word of the Year winners have also been popularised by modern technology ('selfie') or by modern media: 'simples'; 'bovvered' (one suspects Catherine Tate’s creation Dame Lauren Alesha Masheka Tanesha Felicia Jane Cooper would be an apt touchscreen-engrossed postergirl for the undernourished Millenial); and, a personal favourite, 'omnishambles', immortalised by one of the most dexterous linguists of 21st century television. We may not use these words in a decade, or a century from now, but they capture cultural zeitgeists in a way that is unique - especially given the speed at which they abate.

Two books also came to mind when I read of the announcement. The first is Oliver Kamm's excellent Accidence will Happen: The Non-Pedantic Guide to English Usage, the basic thrust of which is that language's beauty lies in its slipperiness, its constant flux; and that grammar pedants often overlook the primary objective of the written word: to communicate. Linguistic rules are merely conventions, Kamm argues. The other book was Simon Loxley's Type: A Secret History of Letters, which (admittedly farfetchedly) suggests that in the near future we will cease to use letters and words to communicate, instead relying on a series of iconograms and emojis - on its publication, in 2006, most of those in the emotional vanguard were expressing themselves using a concoction of punctuation marks, rather than emojis as we know them today.

A world in which Loxley's thesis materialises is a near-impossibility: as in many other areas, the heralded full-scale digital apocalypse/revolution/etc is unlikely to fully materialise; old habits and conventions will almost certainly remain, albeit changed, and reside alongside new behaviours, devices, platforms - and keyboards. Where a loosening of the grammatical collar is more often than not permitted (or indeed unseen), perhaps we ought to grant emoji users a similar freedom. Most can still write, still read, still communicate - and like Renton, there's every chance they can do so in more codes than you, too.

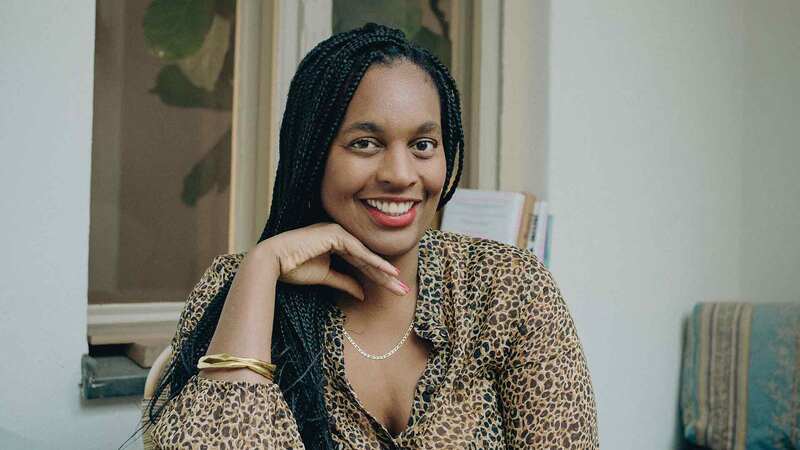

Danny Arter is The Bookseller's creative editor.