You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Customer choice or self-censorship?

Publishers and distributors face hard decisions when international legislation creeps towards censorship.

US children’s publishing and distribution giant Scholastic has been battling a PR crisis. Early in October, rumours emerged that the company had carved out a section in its school fair book catalogue titled “Share Every Story, Celebrate Every Voice”: an optional collection dubbed by critics as a “bigot button”, which, when triggered, would allow educators to exclude “diverse” titles from displays.

Despite being a signatory to the National Coalition Statement on the Attack on Books in Schools, Scholastic defended its decision, drawing attention to legal risks facing US educators from new laws that have stymied teaching on issues of race, gender and sexuality. But accusations that Scholastic had become a willing accessory to censorship grew after high-profile children’s authors and freedom of speech advocacy group PEN America urged a different course. On 25th October, Scholastic announced it would withdraw the collection, acknowledging “pain caused” and “broken trust” over the publisher’s decision “to segregate diverse books in an elective case.”

Scholastic’s book fairs are an obvious focal point for censorship. They’re big business and a key way that Scholastic gets books into the hands of young readers. According to the company’s latest Q4 earnings, the fairs accounted for two-thirds ($180.5m) of the children’s book publishing and distribution division’s revenue ($291m). While this case marks an expansion of constraints affecting teaching to those affecting the sale of books to children, it is also striking in its resemblance to much earlier censorship controversies surrounding the distribution of books that address LGBTQ+ themes.

Both in the 1960s, and now, in 2023, book publishers and distributors have found themselves torn between the interests of readers and politically-motivated regulations, resulting in subtle forms of self-censorship at the point of sale

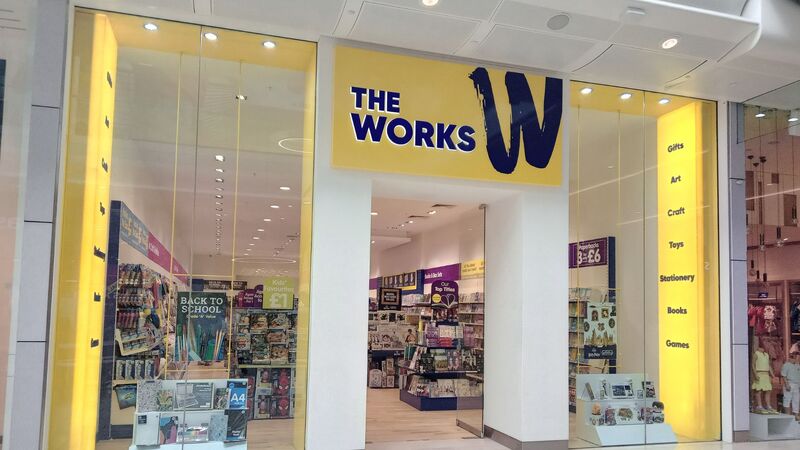

For example, in 1960s Britain, major book distributor W.H. Smith found itself limiting customer access to what it dubbed “controversial” literature, in response to obscenity legislation. This meant titles that included violence or sex — but books with LGBTQ+ content of any kind (even if not explicit) often fell under this category automatically. The firm hired expensive lawyers to advise on whether or not it should sell individual titles (often at rates that exceeded the sales revenue of the titles themselves), such as Sanford Friedman’s sympathetic coming-of-age novel Totempole (1965) or Gore Vidal’s Myra Breckinridge (1968).

The firm restricted access by not allowing branch managers to stock these — and similar titles — in their retail outlets. Instead, a system known as “customers orders” allowed the firm to claim the books were still technically available, but a customer had to go through an elaborate series of steps (and pay a fee) to order the books. The company claimed to facilitate choice — customers could order any book in the vast catalogue — but this relied on the customer’s prior knowledge and determination.

Smith’s practices and dominance as a distributor made it a target for accusations of censorship. By its own figures, it sold 15% of all books and 30% of all newspapers in Britain. (Scholastic’s book sales, aptly, command ~30% of the US children’s publishing market.) Smith regularly tried to defend its decisions by citing the difficulty of navigating obscenity laws which were both vague and arbitrarily enforced. But it was only in the 1970s when the firm fully committed to selling titles that — in the words of its director — were “marginally ahead of public taste” that Smith was better able to avoid public controversy.

Both in the 1960s, and now, in 2023, book publishers and distributors have found themselves torn between the interests of readers and politically motivated regulations, resulting in subtle forms of self-censorship at the point of sale — a central dilemma affecting publishers in markets beyond the US and UK. In recent years, academic presses have also borne reputational costs for amending journal content collections on behalf of their intermediaries, especially in China. The most widely reported case, involving Cambridge University Press, charted a course now familiar to Scholastic, from initial acquiescence with censorship constraints to community outrage, followed by a screeching U-turn. For the affected parties, altering the contents of online journals available in China to suit political interests was deemed unacceptable. But some publishers have sidestepped this requirement by allowing greater customer choice, with journal sales packages tailored by importers according to China’s opaque regulatory framework — a route that has proved less reputationally perilous.

In the Scholastic case, though, this customer-centric approach has been decisively rejected. Unlike earlier controversies, new legislation in the US with censorious intent has been documented exhaustively by journalists and activists. The National Coalition Against Censorship applauded Scholastic’s reversal for “refusing to do the censors’ work for them” — but in the eyes of its critics, the company’s curated catalogues represented a chilling leap beyond the letter of the law.

We applaud Scholastic for changing course and refusing to do the censors’ work for them. Those who seek to ban books rely on companies, institutions, and people to censor themselves to achieve their goals. pic.twitter.com/kGXn87KVkv

— National Coalition Against Censorship (@ncacensorship) October 26, 2023

Amid speculation that publishers might alter the content or kinds of titles they commission in response to changes in US state law, publishers have largely held a firm line against activity which could be perceived as censorship. However, as both a publisher and a distributor of its books, Scholastic was caught between conflicting interests at its nationwide book fairs. As a prominent voice in the anti-censorship campaign, its actions to separate diverse titles not only played into tropes of ghettoising diverse literature but also came across as hypocritical. It remains to be seen whether the same reputational costs await distributors who choose to pursue more subtle means such as altering platform algorithms or (re)tailoring catalogues.

If the lessons of history are instructive, they tell us that lines of defence around facilitating customer choice rarely sidestep controversy. But if the past does offer hope, it is in this: when publishers and distributors resist doing the work of law enforcement, they push the burden of these terrible laws back to where it belongs — on the politicians who created them.