Cutting through the Babel

AI will only fulfil its potential with help from publishing’s human talent.

I’m just back from a week at Frankfurter Buchmesse. It was an important moment of reflection. Not only did it let me consider a year’s worth of interactions with publishing, since my company, Shimmr AI, launched at last year’s Book Fair; it also caused me to consider the nature of "people in books".

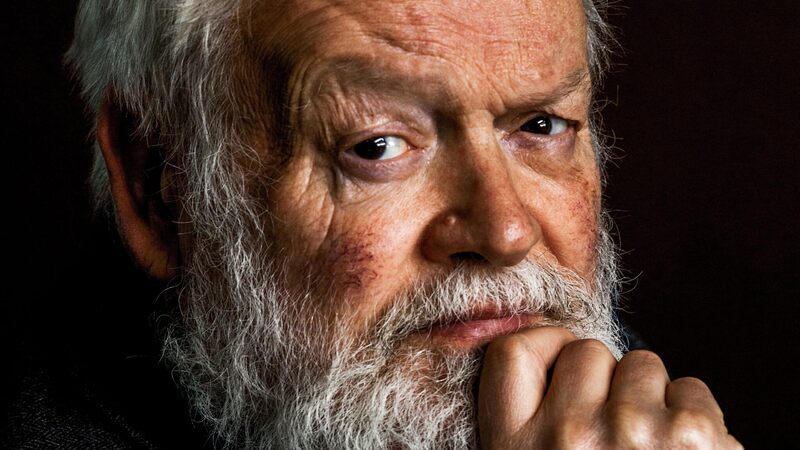

I’ve had a long and multi-faceted career, initially as a consumer psychologist working across a wide spectrum of "verticals", including finance, personal care, travel, insurance, communications, advertising, design and cultural curation, then founding and running brands in disparate industries including whisky, music and food, before bringing much of my experience together within the advertising business that is Shimmr, and its intersection with AI.

Throughout the decades of professional relationships across these industries, I’ve found those that I’ve developed with people in publishing are characterised by exceptional empathy and articulacy. "Book people" are thoughtful. They express nuanced views with ease. One feels understood, or at least listened to with attention and effort. There’s sophistication in evaluation and communication. I don’t mean to be dismissive of great communities with which I’ve previously worked, nor sycophantic to the population with whom I now trade and commune and where I’ve made great friends. It’s just very apparent.

Authors, agents, librarians, editors, publishers, salespeople, marketing teams, senior management, people in specialist publishing communities where much is written and shared—they’ve all shown an unusual fluency with empathy and expression. "Publishing" has a remarkably well-developed capacity to feel and think, and to employ language to express the product of both those things. In neuroscience, it’s often referred to as system one (our implicit, reflexive, empathetic, fast-feeling capability), and system two (our explicit ability to rationalise, communicate and express, or more slowly think). It’s a pleasure to be around people who synthesise these two systems so well.

It’s made me wonder what causes this. Of course, there’s some self-selection—long-form content is what books technically represent, and it takes effort, dedication and self-awareness to enjoy immersing yourself in something that takes a while to be revealed. This isn’t for everyone. It’s also clear to me that the very nature of literature helps to "train" the publishing workforce. There’s lots to think about as one reads, and as it takes place, feelings float in and out of our beings, sometimes foregrounded, sometimes backgrounded. Reading is such an immersive occupation and it’s multi-dimensional, excluding the mundane distractions of the hour, including mental focus, allowing dawning realisations alongside forensically focused discoveries. It’s a complex system that utilises many human capacities, despite giving an impression of "just sitting there".

AI won’t get out of control if we maintain confidence that the very things that have made publishing so special will endure.

Books make us feel and think. They exercise the parts of us that make humans human.

As I’m also immersed in the world of AI, and my posture towards it is that it’s an allied intelligence, created by our minds, I wondered about just how AI might end up most effectively intertwining with publishing—after we’ve all found ways to accommodate the reality of its enduring presence in our world.

Perhaps oddly, my mind turned to Babel. Being a little inexact, Babel’s a place of interminable words, where everything that has ever been written is present, and everything that will be written will appear, and words about words abound, in every tongue and every style, limitless and so immense as to be unfathomable. A bit like a large language model (LLM).

I was reading an extract from Jorge Luis Borges’ The Library of Babel. It envisions an infinite library made up of identical hexagonal galleries containing countless books. Each book is unique, yet filled mostly with meaningless text, with only a rare few offering coherent ideas or truths. The narrator, a librarian, reflects on the library’s structure, the endless search for meaning within its volumes, and the simultaneous despair and hope this pursuit generates. Believing the library to be an eternal, divine construct, he ponders the futility and beauty of a universe where every possible combination of letters exists, yet most offer no discernible sense. A bit like our fear of the rubbish books LLMs might write (if foolishly tasked to do so).

This series of reflections has brought me to a happy place. Faced with this giant generating machine called AI, newly in our midst, I think we should not flinch (once we’ve defended boundaries such as copyright, of course). It will bring efficiencies to publishing in all the anticipated places (like better inventory management, easier legal constructs, faster payment systems, some copy-editing) and it will bring emancipation in others (like new creative directions, innovative conceptualisation, collision of forms). It won’t get out of control if we maintain confidence that the very things that have made publishing so special will endure. They are just what we need to help us navigate this new force. Intelligent evaluation and sophisticated expression, each imbued with that deeply human ability to feel and think, will guide us.

Large language models are just slightly more decipherable Babels. Within them reside all the bad, and all the good, of human output. As ever, it’s up to us to choose which parts to use.