You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

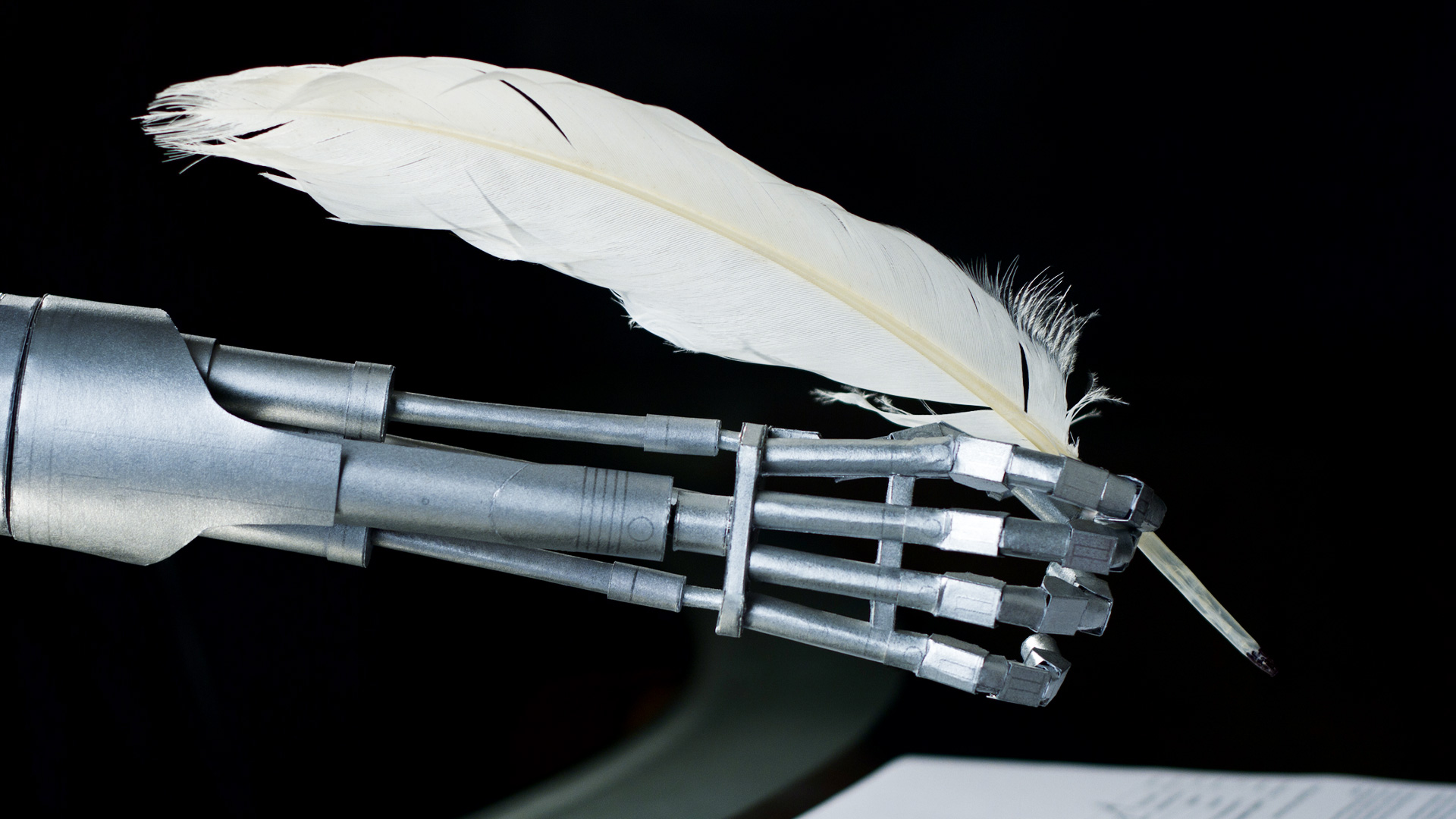

Dancing robots

"Like most other writers and poets", J G Ballard writes in his 1961 story "Studio 5, The Stars", "he had spent so long sitting in front of his VT set that he had forgotten the period when poetry was actually handspun."

Ballard’s fictional poetry-writing "VT set" foreshadows – like so much of his work – the world to come, in this case AI’s ability to write poetry. Almost uniquely among the language arts – and true to Ballard’s story – poets are embracing this new technology, expanding an art form that has never sat still.

This isn’t to say that poets, like most writers, aren’t concerned about the free use AI is making of writers’ words, bypassing the payment of rights. Writers are advised to check out ALCS’ campaign to ensure their intellectual property is paid for when it’s "machinespun" through AI. The current ALCS survey usefully asks writers if they have used AI in their own work, making a distinction between AI tools that ’generate’ output and AI tools that "assist" output. It’s this last area that many poets are experimenting with.

There’s not a poet out there who doesn’t want to be paid for their work but imagining a world where AI wouldn’t be a creative theme – and a creative tool in itself – would be like imagining a world in which The Matrix wasn’t made in the wake of the internet.

Poets are the lock-janglers of the arts, trickster-figures who love to get inside the Boolean system blindfolded to do some re-coding of their own. I’ve not met a poet yet who’s shown concern that AI might produce a poem that would challenge the artistic merits of their own work. Despite generally being paid less than other writers – and perhaps partly because of this – poets are displaying a healthy confidence in the uniqueness of what they do.

I have a novelist-friend who asked AI to spit out the plot for the novel he was thinking of writing and although he didn’t use the results, AI did an impressive job. Poetry, though, is a different kettle of phish. Alan Turing knew this and famously made the point that an advanced computer would say "no" (not for the first time) to being asked to produce a poem because it would understand its own limitations.

The critic Jeremy Noel-Tod compellingly argues on his Substack "Some Flowers Soon" (if there’s one poetry blog you want to pay for, make it this), that there’s a solid reason why the new technology will never be able to produce poetry that will put poets out of business, as the technology it works on is anathema to the nature of poetry.

I’ve not met a poet yet who’s shown concern that AI might produce a poem that would challenge the artistic merits of their own work

This is because AI poetry involves what is, revealingly, known as "smoothing". Programmers add smoothing to a Natural Language Processing model in order to enable it to predict the probability of word combinations not found in the text it has been trained on – including words not encountered before. Smoothing aims to improve accuracy by improving the prediction of probability.

Great poets often revel in being slightly "off", a deliberately missed stitch brings a human-touch to the artform. We’re also a vicarious species, we want the scent of ecstasy – and suffering – in the poems we read, which the glitchy spittoon of computer output will never ring out.

But poets are finding some delightfully creative outputs with AI. And let’s not forget that the penultimate chapter in James Joyce’s Ulysses uses this exact technique, as his invented computer asks – and answers – questions about the novel we’re reading. Through Joyce and Ballard’s prefiguring of AI it could be argued we’ve created the literary device that writers always imagined.

Poets have entered the matrix. Barrie Tullett’s DanteggiareAI – credited to "no human hand" – is astonishing, not for the quality of the poetry produced but for the imaginative drive behind the prompts: "ChatGP, write a version of ’Canto One’ of Dante’s ’Inferno’ as a stream of consciousness as if it were written by children’s author Enid Blyton."

For the reader, the interest comes in the interaction between human prompt and machine – it’s like watching someone trying to teach a robot to dance. Tom Jenks has been at the forefront of digital experimentation for well over a decade and has poems featured in a new magazine called The AI Literary Review, edited by Dan Power, whose first issue features 10 poems, "each a collaboration between a human poet and their AI muse".

Other contributors include Sylee Gore, Karólína Rós Ólafsdóttir and Roz Counelis. The submission guidelines are explicit on what they want: "We are not looking for poems ’written by AI’ – we’re looking for poems written by humans using AI as a creative tool."

Published last year, Hannah Silva’s My Child, My Algorithm brings queer single parenting into conversation with an AI algorithm to create a deeply human book. Hannah uses the new technology to deconstruct received ways of thinking and to reconstruct new ones.

As the muse of Ballard’s story, Aurora Day, expresses about the future dystopia she lives in: "Poetry is dead today, not because of these machines, but because poets no longer search for their true inspiration." And the true inspiration of poets includes all that is contained in the world, including machines that make poetry.