You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

The dangerous debt of gratitude

I don’t like dinosaurs, or cars. I am not interested in trains or engines. I steer clear of enforced gender clothing and regularly put pink nail polish on my son because he likes how it looks on my nails and wants to have the same. Yet despite this, there are some obsessions with things traditionally seen as male that creep into his being and I have no idea how they got there: namely, fire, loud monsters and things that go and go fast. My husband loves it. I am less keen.

While I can lament that I did not get a quietly-colouring-in child but one who has to stop and point every single time he sees a motorbike on the road, it is not how he treats the world that bothers me, but how the world treats him. He is not bossy, he is assertive. He is just loud, not taking up too much space. He is, to be frank, uncontained, unrestrained and liberated. I look at the way he is in the world and I realise that this reaction to his personality will probably carry on throughout his life, into adulthood and beyond. And it pisses me off.

That is not to say that I want my child to be smaller, to be narrower, to feel hemmed in. Of course not. What I want is for every person to have the same elastication in perimeters afforded to them by birth. Because, let’s be honest here: we don’t. That sense of restraint is a winner in restaurants when, most of the time, young boys can be seen making their presence very known compared to young girls of a similar age. But while the girls’ self-control may bring smiling nods and appreciative glances from onlookers, it does not serve those same girls as they grow into women and need to make their presence known to get what they deserve.

Why is it that, time and again, girls can outflank their male counterparts in academia and early potential, yet fall off the higher they climb? There are many many reasons for this, complex and intrinsic and dealt with by far more intelligent and researched voices than mine. But I am going to concentrate on one thing that to me is insidious and toxic, and which I would like to eradicate from the non-male tongue.

Gratitude.

My son is taught to be thankful and appreciative, but by and large not grateful. Gratitude will come later; let me explain why. To be thankful is acknowledgment of the service someone has provided you with, but gratitude is a layer beyond that. Gratitude is emotional debt; it is a word that implies you have been given something extra, something unexpected, something potentially undue. It also implies a certain level of luck. He is three, so the notion of debt is something beyond his comprehension. He is thankful I give him milk when he asks for it, but when he is older, he may feel gratitude that he was born into a socioeconomic bracket that means buying groceries is not an issue. Yet gratitude is a permutation I see across women in the workforce everywhere, and it is something I see misused to our detriment.

It starts young, I’m afraid. I was the grateful girl and chances are you were too. The girl who did what she was told when she was told and so got the good marks and went to the good schools and felt so grateful when she got her degree, so grateful that her teachers recognised her hard work. She was grateful, too, when she got her first job: that she was chosen over so many others who did so well and could do it just as well as she could. What luck. And she was so very grateful when they gave her a pay rise in line with inflation—my goodness, that’s something. The gratitude level goes on and on: that she didn’t get made redundant in the latest round of cuts, or get furloughed, or was allowed extra sick leave for that operation. It never stops.

But here is the thing. There is a point when the gratitude tips into resentment. You didn’t get the job out of luck. You got it because you worked bloody hard and you impressed. You got the degree for the same reason, and it’s why you didn’t get made redundant too. You work and you work hard and the reason you know you are good at it is because you still have a job. This is a transactional relationship between you and your employer. They expect a service for which they pay, and you return that service, for which you are paid. There is no gratitude in it. You are both playing the parts you are expected to play.

Gratitude is what stops you from walking into that room and looking at what you do and asking whether you are being compensated appropriately, because it’s the voice that says, ’Well you should be lucky to be here anyway.’

Gratitude is the pat on the head and look of approval that says, ’Good girl’—just like those quiet little girls in the restaurant. But it is also what stops you from putting yourself forward for a promotion with a job title that either reflects the work you are doing anyway, or offers work you could do and excel at, because you can do your current role with your eyes closed.

Gratitude is what is holding you back. Gratitude is bullshit.

I am grateful for a lot of things: my health, my child, my husband, my house—and, yes, my career. Do you know to whom I offer that gratitude? God. A higher power and guide. What I refuse to give gratitude towards is the workplace. I am thankful for the flexibility, trust and support from my colleagues; for their counsel, wisdom and kindness. I hope I give that in turn, and I aim every day to reflect that back in my attitude and work. I look, therefore, for balance.

Gratitude is a debt and I would ask you this: is it a debt you have earned, and what exactly do you need to do to pay that debt off?

So I advise: stop being the good girl in a restaurant, stop being grateful. Knock over the salt, ask for more bread. Untie this one string from around your form and expand.

The room can take it. There’s so much space waiting for you to claim. And when you do claim that space, just say: “Thank you.”

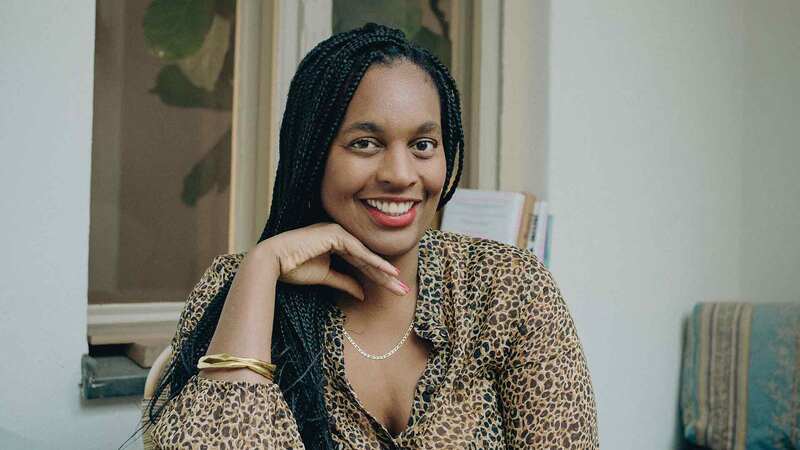

Nelle Andrew is an agent at RML. She was named Literary Agent of the Year at the 2021 British Book Awards, and was a Bookseller Rising Star in 2016.