You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Dear Will… creative writing courses matter more than ever (but not for the reasons you think)

Dear Will,

We’ve never met, though I am familiar with your work, and your opinions about the world, as you have over the years, built up many column inches to your name, especially, recently, on the value of creative writing courses, and the fact that no one is making money as a literary novelist anymore. I also want to note that your controversialist's question is often on heavy rotation in the literary press - Hanif Kureshi had a similar conniption last time he had a book to promote. But since this is a matter quite close to my professional heart, I would like to point out a few glaring errors of logic in your critique.

Firstly, the linking of Creative Writing with money. Since when has the financial status of the author given us any clues as to the literary merit of the work? Kafka’s The Trial sold 800 copies of its first print run, the publication of Ulysses bankrupted Sylvia Beech at Shakespeare and Co, James Baldwin was out of print for years. The history of literature is littered with examples of impoverished artists, poets, vagabonds and troubadours. Your argument seems to me to sit at the heart of the kind of neoliberal thinking that you claim to eschew, namely the equation of financial reward with literary merit. Art should surely be for art’s sake? The rest, as Raymond Carver would have it, ‘is gravy’. Books have always been written under the most impossible of circumstances; ask any writer with a pram in the hallway.

Added to this I would like to point out that you were lucky. You came of age in a period, between about the 1970s-2000s, when there was stability in the literary market. There was such a thing as the Net Book Agreement which stabilised book prices and your books, which represented the arch postmodern decadence of the 90s fin de siècle, had some kind of cultural resonance. But it was also - it seemed to me, who lived through this period - something of a monoculture of straight white men. Straight white men who were all publishing and being written about as the writers we should aspire to become. When every book, whatever its merit, was an ‘event’. I can’t begin to explain to you quite how alienating this was. The same names in the same newspapers for the best part of a decade: Amis/Barnes/McEwen/Roth/Updike/Franzen. Yes, there were a few representative others thrown in, but the gatekeepers were few and powerful, and the media monopoly meant that marginalised, or other voices rarely got a look-in beyond the token.

Since then, circumstances have changed quite drastically. The internet has opened a strange Pandora’s Box, revealing the insides of the human mind - perhaps more visceral and vivid than any of us could have imagined. Knowledge, information and mis-information is available to everyone, and the monolithic idea that one ‘genius’ (usually male) writer synthesised all this knowledge for the consumption of the masses is a concept deader than the CD, while text and its dissemination has proliferated, and we are actually reading and writing more than we ever were before.

Which brings me to the matter in hand. Creative writing courses. That Jurassic chestnut. Having been teaching on them for over 25 years, I can attest that these courses are popular not because all the students see the course as a one way lottery ticket to Gringotts, but rather that in an age of information overload, a creative writing course – especially at MA level – gives students time to think.

I grant you the name ‘Creative Writing’ is perhaps too kindergarten for some to take seriously, but on another level, to be creative, solve problems and imagine new futures, one must be prepared to play; to go back to that childhood zone where everything is unfamiliar, new. Also, inside creative writing courses, students are encouraged to play but crucially to read. Attentive and intelligent readers are what every writer really wants; why then condemn them for wanting to know how to read as well as write? Teaching creative writing is also teaching literature - and taught well, it should be encouraging the kind of deep critical thinking you would get on any literature course.

To assume that people go to university to learn things that will then go on to make them money takes me back to my original point. Financial value has always been a horrible metric for matters of human thought and development. What value do we place on citizens who can think better, have better self-knowledge and provide creative solutions to the slow crap apocalypse we’re all facing?

Published books are currently more diverse than I can remember in my lifetime. There are many exciting voices emerging from communities who for years have been suppressed and marginalised. There is a fresh wind blowing through the world of letters and to me it feels as if a blockage has come unstuck. We are all enriched by this new polyphony, especially in the immeasurable parts of our psyches where all deep thinking and deep listening is conducted.

Your faithfully,

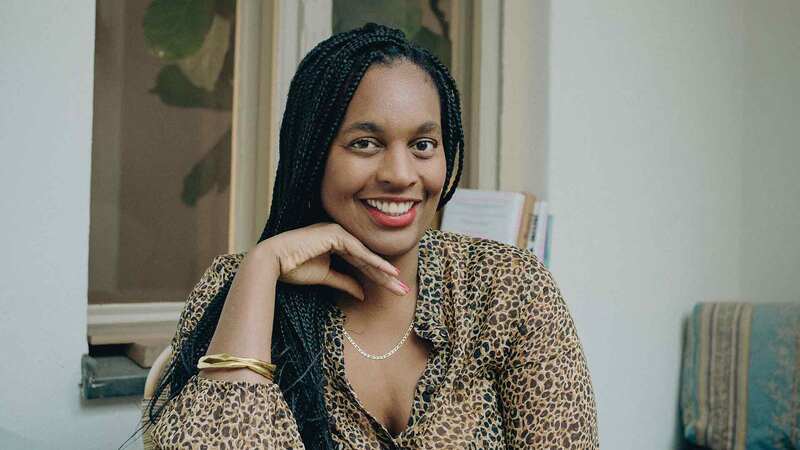

Julia Bell

Course director

MA Creative Writing,

Birkbeck