Does not translate

AI can never match human translators—but we need authors to support us.

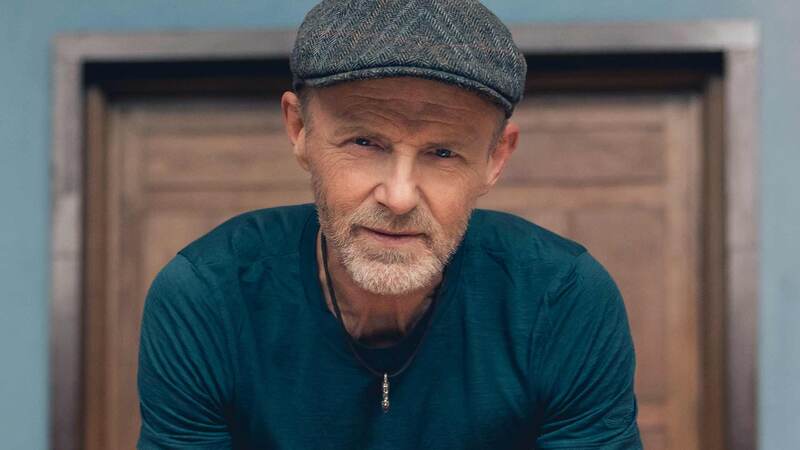

As a translator I’m deeply concerned about the rise of AI, particularly in terms of using it to translate literature. As an author, I know that I weigh every word on a scale, always questioning if a particular word has earned its place in the book or if it conveys exactly what I want it to convey, in terms of meaning, atmosphere, character and the setting or time period that the word pertains to. A book, any book, is a work of art. So why would you even consider running it through a machine?

When translating the works of other authors I’m equally careful in the choices I make, and every tiny decision brings something to the text as a whole. When I, as a human (how dystopian to have to write that), translate a work of literature, I go deep inside the text; I learn as much about the characters and the world as the author. A very simple example in a book I recently translated relates to different characters, and whether they would drink coffee out of a mug or a cup. The same word in Swedish became two different words in English depending on who was doing the drinking. This is just one tiny detail, and a nuance that a machine could never distinguish between. In this case it doesn’t matter if a literary text is post-edited by human, because a human editor would only notice these details if they’re working deep in a text, deep in that world, translating from scratch.

Although AI hasn’t quite caught up with literary translation yet, the knowledge that it is there is making it harder for translators to charge their going rate.

Being a translator is an invisible and underrated profession. Invisible because we work in the quietude of our own homes, unnoticed by the world at large. A Swedish book appears in English and few readers think about how it came to be, that it can take a whole year to translate a novel. And underrated because translation is not a matter of switching one word for another. A language contains a whole culture, a world view; it is connected to geography, history and ways of thinking. If I say “Jul” in Swedish it is not the same as “Christmas” in English. We have no King’s speech and no "Eastender" specials—no turkey, even. These are all things to consider when translating Christmas scenes in a book.

It is this lack of awareness, the invisibility and lack of insight into our skills, that is making the machine takeover so easy. Compared to paying a year’s wage to a human being, AI seems cheap. But in my view there is no price that can be put on the damage that is being done by AI to text production.

I know that technical translators—in whose field AI has already made huge advances, making work scarce, pushing down prices and shifting the focus from translation to machine translation post-editing (MTPE)—have already left the profession in droves, to do literally anything else.

Although AI hasn’t quite caught up with literary translation yet, the knowledge that it is there is making it harder for translators to charge their going rate. I’ve experienced this myself with publishers changing their minds about paying for a translation. It is depressing and demoralising to be actively devalued in this way and, of course, the unwillingness to invest is also reducing the amount of work available.

I’m aware that publishers are making noises about using AI, but I for one, as an author, would never sign away my book to a publisher that will use AI to translate it, and if you care about your literary work, you won’t either. This is the power authors have to stop the trend.