You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Don't marginalise migrants

Publishing must do more to surface and support valuable migrant voices.

I left Greece in 1999 and came to the UK to study. Since then, I’ve lived at 32 different addresses, worked in restaurants, factories and libraries, met people I would have never had the chance to meet in my home town, and written a novel. I’m one of those people who stares at the floor a lot, but once every two or three years, I look up and realise where I am. And it hits me: if you’ve never left, you’d never have done this.

That is my story. But anyone who has moved to the UK from another country, whether as a refugee or migrant, has a similar experience, sometimes more dramatic and certainly fascinating. We all carry some cultural baggage with us and often view the world through a unique outsider’s perspective. And we are 14.4% of the UK population – roughly one in seven of the crowd in your bookshop or the bored commuters on the train home. Yet while the publishing industry is slowly improving diversity, this often stops short of representing first-generation migrants and refugees at a time when they are in the public eye. Although it is hard to find data on this group directly, 91% of published authors are white, and two-thirds of those working in the industry come from professional backgrounds. By contrast, recent waves of migration have included EU citizens working in hospitality and trade, overseas care workers from Nigeria and the Philippines, and international students from China and India among other nations. As a recent Spread the Word report noted: “Do not cater only for ‘Susan’. Rethink the idea of there being a ‘core’ audience and understand that modern Britain consists of multiple audiences.”

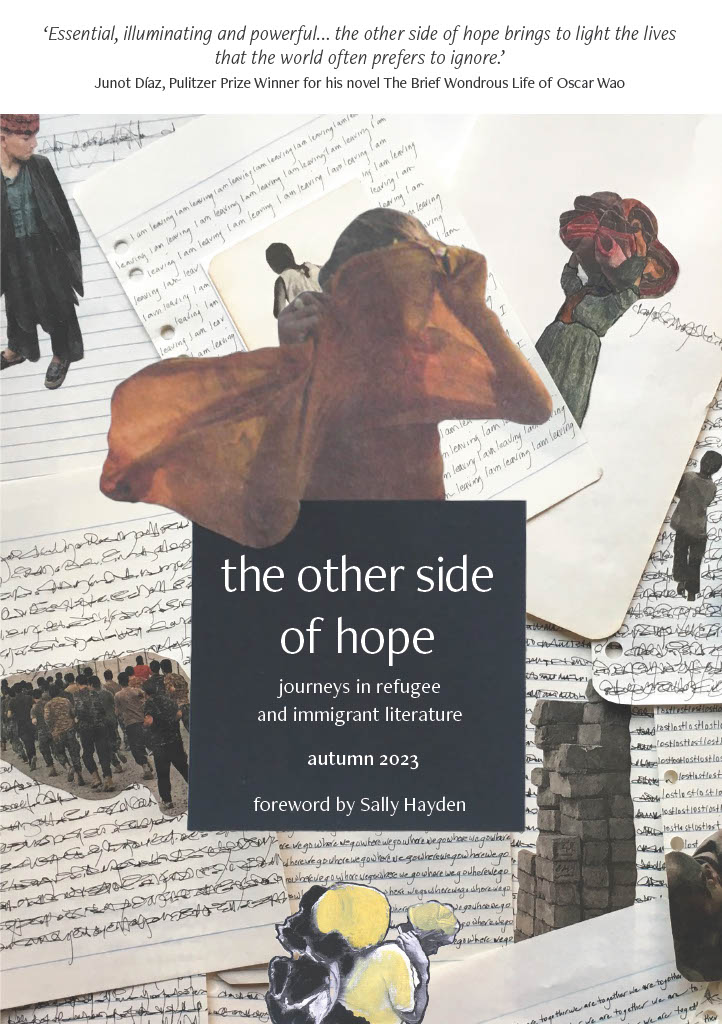

It was to address this gap that I set up The Other Side of Hope in 2021, a literary magazine edited by refugees and migrants and containing stories written by these groups as well. The idea came to me at a time when I was both delivering creative writing workshops at a refugee charity, and also sending out short stories to literary magazines. With funding from Arts Council England, I created a team of editors. We publish poetry, fiction, non-fiction, book reviews and author interviews. So far, we’ve published three print issues and two online, with the third due to publish later this month. In January, we’ll publish Other Tongue, Mother Tongue, a separate project where writers send us their work in any language, and we publish them alongside the English translation.

While the publishing industry is slowly improving diversity, this often stops short of representing first-generation migrants and refugees at a time when they are in the public eye

The Other Side of Hope aims to be a quality literary magazine, but there are a few things we do differently. Firstly, it’s inevitable that we will have to reject many submissions, but we try to do so in a way that isn’t crushing. If we do reject a submission, we encourage them to work on the writing and send something to us again. And we don’t reject on technicalities. If someone submits without a cover letter, or doesn’t specify what genre it’s in, we’ll email back and say: “Can you tell us more?” Hopefully this way people feel more comfortable. We also avoid submission forms, because people who have dealt with the immigration system, especially those who have been in the asylum system, have filled in enough forms already.

We also know that people writing in their second language often lack confidence. While we encourage them to submit the best work they can, we know that sometimes it is difficult to write perfectly. We encourage them to ask for help with proofreading. And the reason we recruited refugees and migrants to staff the editorial team is that we wanted to create opportunities in the publishing industry for editors in their second language. (Of course, there are many migrants from the Anglophone world as well). Our team includes a lecturer in Arabic literature and a Kurdish Iranian film-maker, who bring the skills they developed in their home countries to the magazine.

Several of the contributors to our magazine have gone on to publish collections or novels. The Other Side of Hope is stocked in a dozen independent bookshops around the UK, as well as countless libraries. However, when someone moves to the UK from another country, they have to build their network from scratch.

That’s why it’s not enough for us to publish the magazine. We need agents to read it, bookshops to champion it and publishers to make the representation of migrants a priority. The Other Side of Hope is working with AM Heath to identify six contributors who would benefit from one-to-ones with their agents. Elsewhere, Footnote Press and Counterpoints Arts have launched a prize for narrative non-fiction from refugee and migrant writers. It is this kind of eco-system of opportunities and constructive feedback which leads to real change.

And this isn’t simply about ticking a box – we all benefit. Our writers and editors want to touch their readers. They want to create something beautiful that enriches the lives of everyone, not just people from a refugee or migrant background, or the charities that support them. We want to reach people who like literature – even those who don’t like refugees. And by handing the pen to refugees and migrants themselves, publishers can find more interesting stories. Our magazine contains writing about the refugee experience, but it also includes pieces about falling in love while serving tables, and a story narrated by a plant.

Refugee and migrant writers might currently be marginalised, but with the publishing industry’s help, we can bring the mainstream into the margins.

Alexandros is a International Migrants Day Ambassador 2023. You can meet the others and find out about the programme here.