You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Folding eight times: the everyday impact of burnout

If you’re finding it hard to make it through the day, you don’t just need coping strategies — you need structural change.

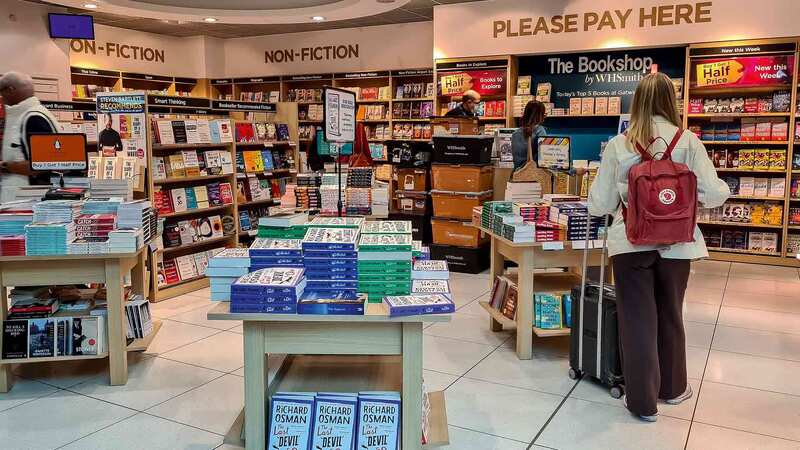

It’s hard to write when you’re not motivated. This is something I tell my authors all the time, particularly the ones who apologise for not sending me any work to read after a particularly difficult spell, a bout of illness or an intense period at work which consumed them too much to write. It wasn’t until I caught up with one of my former mentors at The London Book Fair that I was reminded of the fact that this applies to me too.

I am very privileged to have this space in The Bookseller to express my thoughts, start and continue discussions we are having about the industry and working within it, but recently with The London Book Fair returning, the cost of living rising and my daughter learning to climb out of her cot six months before I was ready for her to, I lost my motivation to write anything. It wasn’t that I had nothing to say, quite the opposite, it was more that I could not get anything down onto the page. I struggled to articulate my thoughts, I self-edited every sentence before it was even finished and convinced myself that no one would read what I wrote or worse, would only read it to make fun of it in group chats. On its own, I would put this down to imposter syndrome, but coupled with the fact that I became cynical and critical of everything I did and was finding it incredibly hard to get started with the most basic tasks, let alone be consistently productive, I realised that I was on a one-stop train to burnout town.

For clarity, let’s define burnout. Burnout is most commonly described as a form of exhaustion caused by constantly feeling inundated. It’s a result of excessive and prolonged emotional, physical, and/or mental stress. In many cases, burnout is related to one’s job. Burnout happens when you’re overwhelmed, emotionally drained, and unable to keep up with life’s incessant demands. I feel like I should point out here that burnout isn’t a medical diagnosis, and I am not a doctor, but I have experienced it in many forms throughout my life. A bad day at work leads to a bad week. I’m irritable. I dread walking into the office. I feel like nothing is going my way, or my work is consistently going unappreciated. These feelings linger and begin manifesting into physical symptoms, illness and the unbearable weight of stress. I start genuinely considering walking out and never looking back because I am completely and utterly burned out at work. When I start bringing that feeling home with me to the point of not sleeping, not eating, or enjoying life, I know that I am in peak burnout mode.

If you’re struggling, don’t just find a million ways to stay above water, day to day, but open the conversation about what your leadership team can do to help alleviate pressure on a wider scale

When I was in Year 4, my teacher gave every person in the class a piece of paper. She told us that folding it in half more than seven times would be impossible. Naïvely, we laughed at her and told her we would absolutely be folding that paper more than seven times. One boy insisted that he would fold it 10 times. If you don’t know, attempting to fold an ordinary sheet of A4 paper eight times is impossible: the number of layers doubles each time, and the paper rapidly gets too thick and too small to fold. This logical reasoning didn’t matter to a room full of eight-year-olds though, and my entire class got to work on our pieces of paper, folding, pressing and trying to prove our teacher wrong — because back then, we knew everything. We’d find we couldn’t get past the seventh fold then unravel the paper and start the whole endeavour again. Sometimes I liken burnout to this feeling, of being tasked with folding a piece of paper eight times, then trying again and again knowing I will never get past the seventh fold but still somehow believing I have to.

I know this is not unique to me. Publishing is facing “industry-wide burnout” according to a survey conducted by The Bookseller. Now, I love my job, but the way agenting was presented in the article finally gave me the motivation I needed to write this piece. I wasn’t the only one, Nelle Andrew has also pointed out in her piece this week that there seems to be an industry-wide assumption that the grass is greener on the agenting side. That being an agent is somehow less intense, less demanding and allows for a better work/life balance. It’s not. There are good days, and bad days. There are days where I feel completely on top of everything, where I close a deal, successfully negotiate a higher fee for an author and process multiple payments. Then there are days where I struggle to open a single spreadsheet, and question whether I will ever sell a book again. Being an agent means being a lot of different things, often simultaneously. It means being an advocate, an administrator, a salesperson, a strategist a confidant, an ideas generator — and above all, staying positive even when you want to make yourself into a blanket burrito. It can often mean feeling as though you need to always give just that little bit more. Read that little bit more. Fight just that little bit harder.

It also sometimes means sacrificing evenings and weekends to keep on top of your submissions inbox because you don’t want to take time away from the authors you represent by reading submissions throughout the day. Actively building a list means you don’t want to miss anything sent your way, and the sheer volume of querying authors can mean falling behind if you don’t keep up with submissions reading. As an agency, we are very aware of the impact waiting has on prospective authors (something Anna Vaught highlighted in her recent column too), and we discuss our submissions regularly which means there is always focus, clarity and crucially the space made during our working hours for reading and assessing submissions.

Having structural strategies and support in place is key to tackling burnout, and feelings of being overwhelmed. So, if you’re struggling, don’t just find a million ways to stay above water, day to day, but open the conversation about what your leadership team can do to help alleviate pressure on a wider scale. Burnout is affecting everyone at all levels, so if junior staff are struggling, leadership teams need to be reacting swiftly with empathy and tangible support. It is only by sharing, discussing and flexing our workplaces and patterns on a deeper level that we can achieve real change — and, please, for all our sakes, a bit more balance.