You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

In defence of minority languages

Minority languages in literature must be given the respect they deserve.

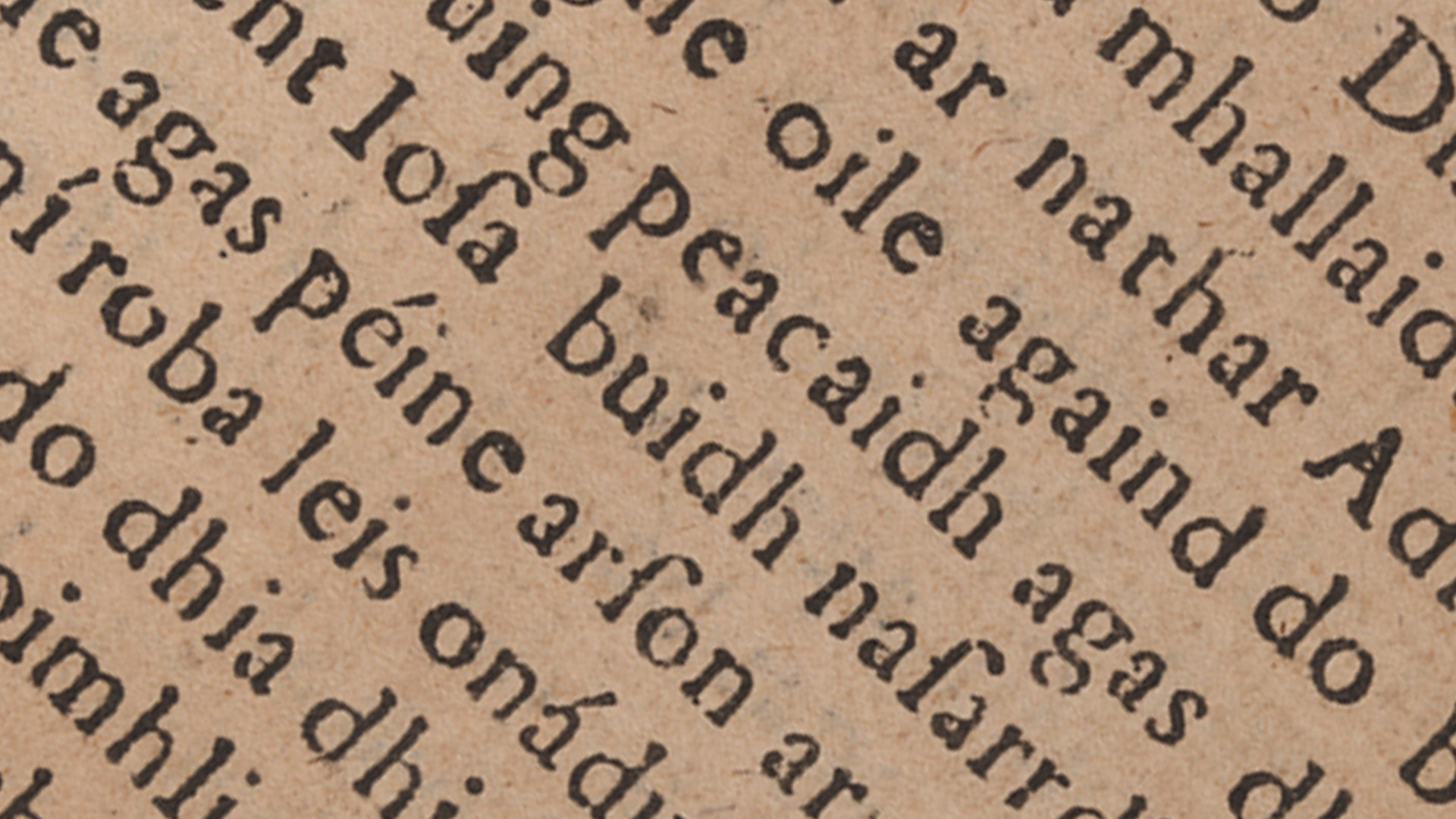

On Thursday 7th December, my friend Taylor Strickland, an American author now living in Scotland, won the Scottish Poetry Book of the Year award for Dastram / Delirium, his translations of the 18th-century Scottish Gaelic poet Alasdair Mac Mhaighstir Alasdair. Taylor, during his acceptance speech, declared the book to be "a symbol of cultural embrace", and asked that audiences "embrace cultural diversity from here on out".

The day after Taylor’s win I was idly scrolling through TikTok, the exact sort of activity occupying time when you know you’ve got Christmas presents to wrap, an article to write, and a week’s worth of tidying to catch up on. As I did my usual mantra of "one more video, then that’s it" I came across Muireann (@ceartguleabhar)’s video on American fantasy author Rebecca Yarros, and her usage of Scottish Gaelic within her bestselling novel The Fourth Wing. What could have been an opportunity to further celebrate the growth of minority languages, a chance to admire an author’s desire to learn a promote endangered languages, instead became an example of myopic, egregious appropriation.

Yarros, on stage at New York Comic Con, gave the host, Popverse’s Veronica Valencia, a rundown on the correct pronunciation of Gaelic words used in The Fourth Wing, however, the first problem came with the very first explanation as Yarros claimed to have used Gaelic, pronounced Gay-Lic and referring to Irish Gaelic, in her book, when her book actually utilises Gaelic, pronounced Gah-Lic and referring to Scottish Gaelic. Rebecca Yarros then went on to utterly butcher the pronunciation of every Scottish Gaelic name within the book, demonstrating a lack of research or care beyond simply checking the etymology of Gaelic words chosen.

This is symptomatic of a wider problem in literature, one in which languages, and particularly minority languages, are used to create an air of myth and exoticism

This is symptomatic of a wider problem in literature, one in which languages, and particularly minority languages, are used to create an air of myth and exoticism. The languages, therefore, become nothing more than a visual pleasure, without care or attention to the fundamentals of the language used. When Cymraeg poet Menna Elfyn was arrested and imprisoned twice for civil disobedience in the 1970s and 1980s, her protest didn’t exist to ensure that monoglot authors could infuse their books with lazy symbolism. No, Menna Elfyn, like many minority language speakers, did so to preserve the history and culture of their language, to maintain their tongue for future generations, and to protect it from the hegemony of the English language. It is therefore absolutely essential that languages are given the respect they deserve, a respect synonymous with the efforts of advocates and activists to revive and protect those languages, a respect that ensures authors "embrace cultural diversity from here on out".

Through Broken Sleep Books, I have published a variety of languages including minority languages such as Kernewek (Cornish), Cymraeg (Welsh), and Scottish Gaelic, alongside others such as French, Spanish, Romanian, Hebrew, German, and Filipino. In doing so, I have endeavoured to learn the pronunciation of the books’ titles, authors’ names and key words before introducing them at readings. This is because names, in particular, carry with them the weight of identity, and it is important to ensure that speakers of a language are able to continue to hear themselves in the words used. As somebody who hears my name pronounced, and spelt, in myriad ways, I have come to find myself pleasantly surprised, and genuinely happy, when people introduce me with the correct pronunciation of my name (I pronounce it Ah-Ron).

Publishing needs to do more to honour, respect, and preserve minority languages. The astonishing 2019 poetry anthology Poems from the Edge of Extinction is a stunning example of how we can do that. The 336-page tome, edited by Chris McCabe, provides bilingual translations of 50 poems in endangered or vulnerable languages from across the world, while providing an overview of the language, poem, and poet. In doing so, poems in languages as diverse as Gorwaa, Mvskoke, Kristang, Jèrriais, Soqotri and Rotuman were given the sort of literary preservation not typically reserved for them. This allows speakers of these languages to finally see themselves represented in literature, and offers an historical conservation for their words. This safeguarding of languages does not work when authors and publishers guess at meaning and pronunciation, instead of giving the words the due diligence they deserve.

If literature is one of the most important methods we have of sharing our experiences here, on this planet, then we fail in that endeavour the moment we treat other languages with disdain. If we ignore the richness of minority languages, the history of their etymology, and the rhythm of their pronunciation, then we close down avenues of creative collaboration and refuse to truly understand the beauty of other cultures and societies.

One more TikTok video into my scrolling, and up pops my friend, and author, Taran Spalding-Jenkin, standing before a live audience and reading the poem "Agan Geryow a Gana Hwath". Translated from Kernewek, the title reads as "Our Words Sing Stil". I am awed by not only Taran’s rich, musical voice, but by words I do not know read in Taran’s mother tongue of Kernewek. If Rebecca Yarros took just a little time to learn how to pronounce the words she borrowed from Scottish Gaelic, then maybe she too would understand that awe.