You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

It's time to decarbonise

The new carbon label from Publishing 2030, a publishing industry accelerator focused on climate action, reflects a speedy, experimental approach to change.

COP27 is around the corner, and Greta Thunberg has just published her anthology of climate activism. In the face of such concerted efforts to tackle climate change, now is a good time to evaluate the publishing industry’s own efforts as we head – with alarming rapidity – towards national, global and corporate deadlines to achieve net zero. Printed books and journals have an incontrovertibly positive impact on society – the fact that Thunberg’s own published work comes in print editions is a case in point. The fact remains, however, that printing on paper does undeniably come at an environmental cost. At Elsevier, for example, we have estimated that at least 30% of our carbon footprint comes from printed books and journals – more on that statistic later.

For the moment, let’s think about the way change happens. While the publishing sector has, to its credit, been very willing to prioritise sustainability, let’s not pretend that change – even when the need for such change is fully embraced – is easy, or swift. One way to make the process easier is incremental experiments to test concepts and share learnings that, if successful, can be scaled up and adopted more widely through the industry – and quickly, if we are to achieve net zero within any meaningful timeframe.

Industry commitment is encouraging but we need more collaboration, and more willingness to abandon the idea of "perfect" net zero programmes in favour of beta-testing pilot schemes and scaling up the ones that work

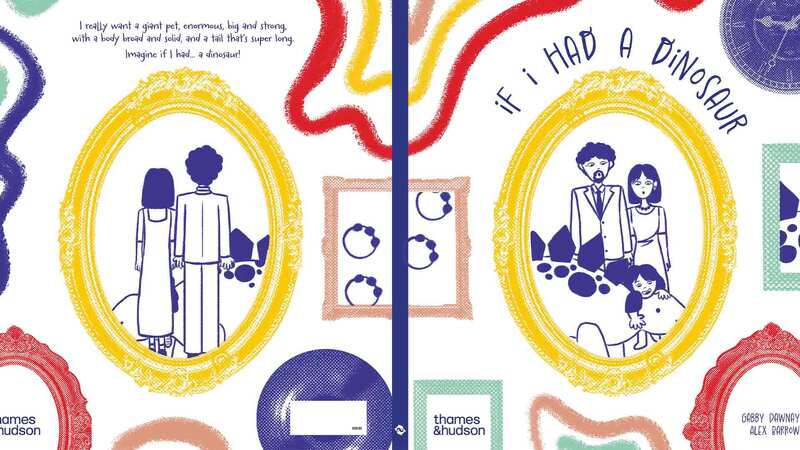

Publishing 2030, a publishing industry accelerator focused on climate action, is doing exactly this with a prototype carbon label to illustrate the emissions involved in the book’s production. Think along the lines of a nutrition label on the meal you buy in a supermarket – the idea is not to demonise a book as either "good" or "bad" based on its carbon footprint, or to promise that a book is "eco-friendly"; but instead to educate, inform, and encourage everyone involved in the publishing process – including the readers themselves – to think about incremental changes that will benefit the environment.

The carbon label is a QR code printed on the back of the book, which is scanned to reveal a breakdown of that book’s emissions, from content creation through to printing, paper production, transport and retail, and finally, end of life. Based on this data, a reader might decide to extend the book’s life by donating it; or a publisher may rethink their paper type. Ultimately, the more data we as an industry generate, the more we can collaborate to understand what "average" and "above average" emissions look like across different industry categories, from children’s publishing to academic publishing.

The next step, now we have launched the carbon label prototype, is to create an open-source app that uses the metadata from the labels to create averages, and so become a decision-making tool that any publisher can use. From a prototype we created in two months and just launched at this year’s Frankfurt Book Fair, we’re now customer testing the carbon label with the ambition to get more publishers on board – and ultimately, to rethink the way they create print books.

Now returning as promised to the statistic I mentioned earlier, which is our estimation that 30% of our carbon footprint at Elsevier comes from printed books and journals. While this figure has been calculated using some assumptions in our methodology, it’s evidence enough to provide a catalyst for new emission reduction projects. Without wishing to sound over-confident, there are some relatively straightforward steps any business can take to reduce emissions (reducing business travel, for example), and after 15 years of our climate action programme, we’re now at the stage where we need to revise deeper-set business practices. The example here is the practice of sending complimentary print copies of journals to Abstract and Indexing services. When this practice first began, it would have made sense. Obviously, times have changed so we decided to ask recipients if they actually still needed print copies. It’s always slightly nerve-wracking to ask people if you can stop sending them things for free, but the response was overwhelmingly positive: a useful reminder that net zero goals don’t exist in a vacuum – most industry suppliers, editors, and academic societies want to reduce their emissions too, and in our experience, are very open to conversations about it.

What did we learn by asking some simple questions on our quest for "press zero"? That free print copies of journals were often redundant anyway, and recipients were supportive when we explained why we wanted to reduce the number we issued. This led to some significant changes in the way we work. We reduced the number of complimentary print copies we produced, changed our policies to ensure free print copies were no longer de facto in contracts, and identified some "carbon offender" journals with high page counts, which we switched to digital-only versions. There’s still more to do, but by reducing the number of journals we need to physically print, we can chip away at that 30% figure.

Time flies when you’re trying to beat the net zero clock. Industry commitment is encouraging but we need more collaboration, and more willingness to abandon the idea of "perfect" net zero programmes (a noble but slow endeavour) in favour of beta-testing pilot schemes and scaling up the ones that work. We need to pick up the pace to meet the one deadline no one can escape.