You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

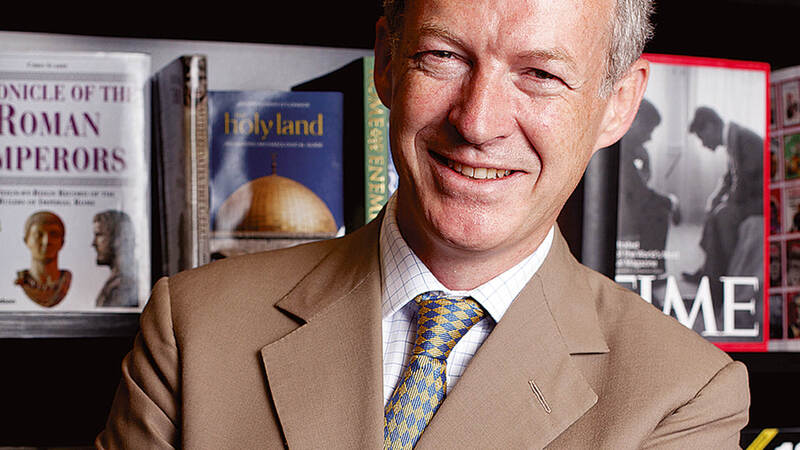

Jimmy six-hundred: Mr Daunt goes to New York

In all of the adulation for James Daunt, current chief executive of Waterstones and incoming chief executive of Barnes & Noble, it is worth recalling that it was not always so. A year after he took over at the business I watched as a senior publisher, visibly upset at how Waterstones had handled the roll-out of one of its biggest titles, physically effaced a picture of Daunt in that week's issue of The Bookseller.

The ill-feeling of this senior executive towards Daunt was not unusual either. Daunt's first few years at Waterstones were troubled. He had pushed and largely succeeded in getting extra discounts from all of the big publishers in return for culling paid-for promotions, including the popular three-for-two deals on paperbacks; he had begun returning huge numbers of books after discovering £20m of worthless stock hidden in back-rooms and under tables across the chain; and had started selling Amazon Kindle devices at a time when publishers were still bruised by the Department of Justice investigation into their agency (fixed priced e-book) contracts.

Back then it was not obvious that Daunt would survive. He'd gone from running six shops (the nickname at the the time was "Jimmy six-shops") to 300, many of them underperforming and a rump of them unprofitable. Earlier in the year, at the opening of the Russian bookshop within Waterstones's flagship store at Piccadilly in 2012, and despite a rare sighting of the then owner Alexander Mamut, I've seldom seen a more depressed bunch of publishers. Daunt once described the decision to bet on e-book sales slowing down and print reviving as "one where you have to look into the mirror, get the bottle of whiskey out and decide what you well and truly believe". Fine words, but hardly confidence-building.

Yet from that point, things could scarcely have gone much better -- the sales decline slowed down, the e-book revolution did stall, the bookshops gradually began to look better and better, and the investment in (and empowering of) booksellers started to pay off. There was a small improvement in sales in 2015, and a bigger leap in 2016 when the business moved back into profit.

With its acquisition of Barnes & Noble, Daunt has gone from six, to 300, and with B&N's 600, nine-hundred stores now effectively under his control. It is a huge gamble, not least for Elliott, whose sudden interest in the book business remains (largely) unexplained.

For Americans, the move also marks a fundamental shift in their bookselling firmament: the departure of B&N chairman Len Riggio, who founded the business with a single college bookstore in 1965 and has been a mainstay even during this recent period of disquiet. As former B&N employee and now founder of Welbeck Publishing Marcus Leaver put it: "[It] feels like the best book retailer of the last generation has handed over the baton to the best book retailer of this generation. Having both Waterstones and Barnes & Noble survive and then, hopefully, thrive is good news for all publishers."

There is, of course, a sort of implausible logic about the deal. Sometime ago I asked Daunt if he'd consider running B&N. Elliott had just acquired Foyles, and the reasoning for going after B&N was not much different: and for Daunt, bookshops (notably book chains) are important and he wants to save as many of them as he can. Declaring an "element of self-interest", he said: "It really matters to us that Barnes & Noble can continue to do what it does, and it really matters that publishers can continue to sell print books through these stores, as well as, obviously, through Amazon."

At the time, Daunt said he'd leap at the opportunity to try and revitalise B&N. Still, even then it seemed far off, and in some ways unthinkable. Despite Daunt's view that both businesses operate in similar ways, there are also massive differences between them, notwithstanding the contrast in the number of stores, the turnover and the cultural differences between the UK and US.

For starters, Barnes & Noble's stores are huge: the chain operates roughly double the number of stores as Waterstones yet its turnover is six times the size. Geographically, too, the sheer breadth of the challenge for one person is staggering. Then there is B&N's recent performance, where the decline in sales has been severe. At its height the group boasted sales of $5bn, but the hiving off of its campus stores and the waning of sales at its Nook e-book business have reduced the business both in size and stature to $3.5bn. The drop of 30% is steeper even than that suffered by Waterstones over a similar period. Perhaps more fundamentally, since 2010 it has made a profit just three times, its faltering performance further exposed by its public listing on the New York Stock Exchange.

On the positive side, BN's web platform is much bigger and more successful than that of Waterstones', while the Nook, despite the tough competition it faces from the Kindle, looks to be an opportunity, particularly if it can get a piece of the growing audiobook market. Like Waterstones, Barnes & Noble has a DNA that is formidable, with many booksellers having stuck it out, even through the lean times. Many have not, of course, particularly at its head office, which after a relatively positive period under former c.e.o. William Lynch, has been in turmoil.

For Daunt the main focus will inevitably be on the bookstores, where he will want to empower booksellers to run their shops in the manner of how Waterstones operates today: effectively as a series of independents, only with the buying power of a chain and the centralising brain of Daunt and his senior buyers. He will focus on merchandising, including non-book, but the drive will be on making the shops attractive to book buyers first, casual shoppers only secondarily. Daunt says he will resist closing stores, but some operate in areas, many out of town, where footfall is perhaps too diminished even for him to work his magic. Nevertheless, his commitment to having bookshops in unfashionable locations is resolute: Waterstones would be a much more profitable business today had he closed some of its underperforming shops. Instead, he has turned them around, or simply made a case that their cultural significance was more important then their contribution.

US publishers, who are said to be jubilant and "pinching themselves" with delight at the development, would be wise to be cautious. It is likely that things will get tougher before they get better. They should remember that Daunt was not an overnight success, he is thoughtful and considered, and while he will want, and should get, their support his aim will be on improving the financial performance of his business, not theirs. He, too, will have half-an-eye on the exit: not his from the US, but that of Elliott, who will likely look to float the combined group.

Publishers should also take time to understand Daunt's singular vision. Gone will be the grand plans and corporate double-speak of the current regime, replaced instead by someone whose message will be simple, to the point, sometimes bruising, but effective.