You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Let's lean into weird

We need more terrifying poetry this Halloween – and beyond.

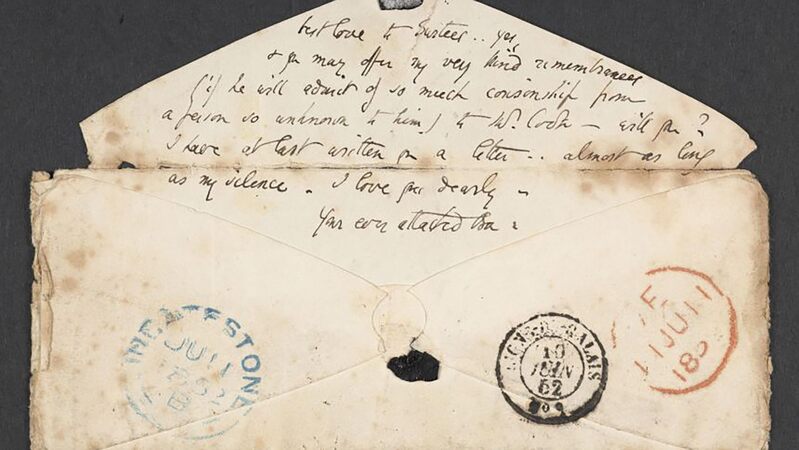

What happened to the weirdness of English poetry? If you look at the first 500 years of the artform, you’d think it was all a bizarre dream narrative involving nothing but the mothers of dragons and visions of towers. Shakespeare had a huge understanding of humanity but what was going on with the pie-baking cannibalism of Titus Andronicus? "Goblin Market" presents a bacchic frenzy and Ted Hughes laid down his poetic legacy with a talking crow. If one of the ways that the artform measures its own success is memorability, then the weird has been an essential part of this: scary poems stay with us because we can’t forget them. With Halloween fast approaching it’s a good time to ask: are publishers maximising the potential of the poetry of horror?

For the first 10 years of my son’s life, we kept a Halloween ritual. Once the trick or treaters had stopped knocking, and the pumpkins were going gummy, I’d pull down a book that contained the scary poem he wanted: Poe’s "The Raven". We’d turn down the lights and alternate reading stanzas out loud, croaking out the word "Nevermore". My son is every inch part of the iGeneration, but he also had an intuition that only poetry could take him where he wanted to be in that moment.

With the current widespread celebration of poetry rooted in identity politics and personal experience – all vitally important – the unconscious seems to have been relegated to its basement. As any therapist will tell you, complete repression of the darkness in us only leads to hobgoblins appearing somewhere else. Poetry, like all art, should be a place for individuals and society to collectively to explore the bizarre, the fantastic and the taboo, allowing everyday life to function better.

In any period of art, the prevalent tastes of the time shape the work that new poets choose to apply their talents to. Publishers play a huge role in this, so why aren’t they pushing for another Poe on their list, someone to create in poetry what Stephen King does in fiction or Cronenberg does for the cinema? One of the wildest imaginations in British literature – the sculptor, novelist and poet Brian Catling – found overground success for his visual art and fiction. The BBC made a documentary about him, and Penguin Random House have published his Vorrh trilogy. Although Catling has developed a cult following, with a TV series of the book being made by Terry Gilliam, his terrifying poetry is impossible to find, published by the tiny (and brilliant) Etruscan Books. You’ll have to search deep down the corridors of small press publishing to find Catling’s monologues in the voice of the Leipzig Cyclops (Late Harping) and his "imaginary conversation" between the author and the death mask of a real-like Edinburgh man called Bobby Awl – as the book is out of print. This gulf between the availability of Catling’s weird fiction and his underground poetry is huge and says everything about how the two genres are treated differently by UK publishers.

Poetry, like all art, should be a place for individuals and society to collectively to explore the bizarre, the fantastic and the taboo, allowing everyday life to function better

American publishers treat their weird poetry better. Alice Notley writes book-length collections about future arks that collect language, about women who descend into an unnamed underworld and try to fight their way out, about creepy fictional detectives who accost the author even in the process of writing the book, about a death in the woods that no one can understand. But unlike Catling, Notley is published by one of America’s biggest publishers: Penguin.

In the UK, our own Geraldine Monk has written an equally incredible body of work involving witches and the occult, all of which is either self-published or made available through small presses. We need to do better in embracing – and pushing – the wildest imaginations in poetry.

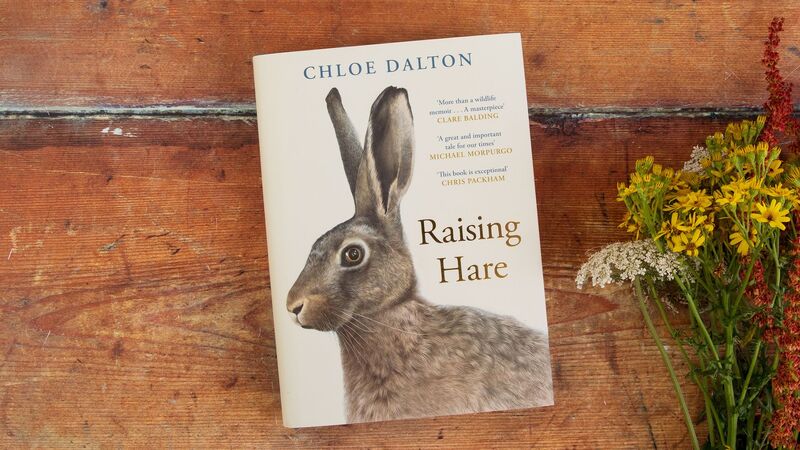

Halloween spending is estimated to total over £700 million in the UK this year, up 13% from 2022. The fiction market, as always, is primed for it. The British Library series of occult stories, approaching 40 titles, shows the appetite of readers for the weird and eerie. Indie publishers such as Honford Star have translated imaginative and unsettling works from South Korea (Bora Chung’s Cursed Bunny) and Charco books are translating Latin American horror to great success. But where’s the upcoming poetry of terror on the UK market this Halloween?

Aside from numerous children’s volumes there’s only one UK publisher who has published poetry anthologies for the adult market: Everyman Pocket Editions, with their Poems Bewitched and Haunted and Poems Dead and Undead, both published as long ago as 2005. There’s a space the size of Sleepy Hollow waiting to be filled with weird poetry. If any publisher needs more of a reminder of the terrifying power of the art form, watch the trailer for horror-legend Mike Flanagan’s new Netflix series this Autumn, "The Fall of the House of Usher". This is of course an adaptation of Poe’s story, a depiction of a warped family, but it’s Flanagan’s decision to bring in the raven from the poem that really makes the hairs stand on end. All it takes, like so much great poetry, is a single well-placed word: "Nevermore".