You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Levelling the field for books

The decision this week by European Union finance ministers to allow member states to reduce VAT rates on digital books (including e-book and audiobook downloads) probably comes a little too late for this errant state, but nevertheless it makes an indelible and important statement: a book is a book.

There is no good reason to tax reading: publishers and booksellers have long won this argument in the UK, most memorably in the 1990s when petitions were delivered to parliament and a tax on books was described as “a body blow for education”. Reading is not just about learning, of course: it is a social benefit. Like Guinness, books are good for us. That said, it is not entirely clear the tax authorities in Europe ever thought taxing e-books and physical books at different rates was a smart idea: the effort of European legislators to harmonise the various VAT regimes in place across Europe dates back to 2010.

In the intervening period, the EU’s direction of travel around e-books has been clear, even if, by fining those countries that independently reduced VAT on digital reading (namely France and Luxembourg), it has sometimes appeared to be taking a detour.

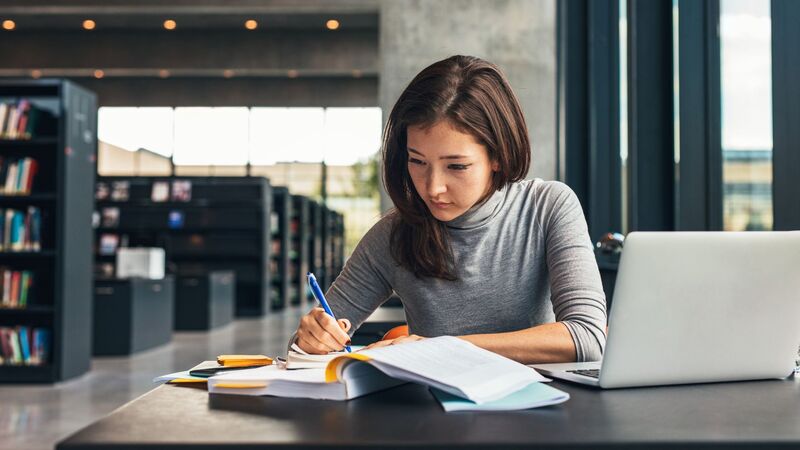

The UK Chancellor could do away with this tax by the time of his October budget, according to PA chief executive Stephen Lotinga—other member states may move even quicker. Not a moment too soon for the downcast e-book market. Perhaps.

As last week’s cover of The Bookseller showed, e-books are hardly in trouble. The advertiser—digital publisher Joffe Books—has sold many millions of e-books, two million alone so far in 2018, but largely outside the industry’s data trail. Add in audio, Kindle Unlimited, self-publishing, and we begin to see how this substantial sector—perhaps worth as much as a third again on top of the print book market—feeds many mouths.

The dropping of VAT on e-books (and audio titles) will probably not provide the fillip some might expect: publishers will want to bank the saving rather than pass them on to consumers, who can already take their pick of e-books from prices as low as 99p. In the US, where there is no uniform tax on books or e-books, the market has not behaved differently over the past few years.

The big publishers will not change their strategic attitude to e-books; they see them as part of an overall offer that includes print books and audio. And the protections afforded to bookshops by publisher control over e-book prices remains an important bulwark to Amazon dominance. Such pricing is not, as some suggest, an anti-digital measure. If we believe in the value of bookshops—as we do books—we must make sure the ecosystem works for them, too. While not all booksellers agree with Waterstones m.d. James Daunt when he talks of being in a “fight“ against e-reading, many will have welcomed the EU’s move through gritted teeth. The last thing they need are lower e-book prices.

The EU may have finally seen sense on tax, but there is still further work to do to make the digital content marketplace a fully-functional part of the books sector.