You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Mapping the poetry aisle

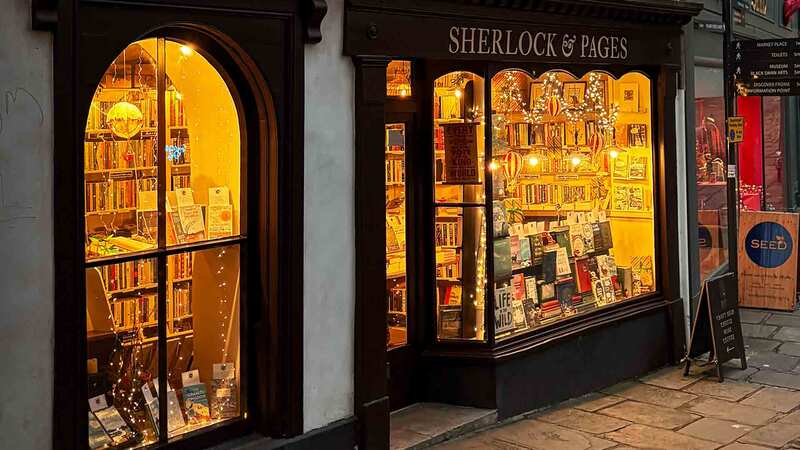

Browsing one of the biggest bookshops in Oxford, I found a history of empire coded into the shelves.

When Meena Kandasamy’s The Book of Desire hit bookshops in Oxford in 2023, the poetry section of some of my favourite shops were stacked to the brim with copies of the book. Its luminous red-pink cover stands out among more staid volumes of poetry. An enthralling feminist translation of one of the most prolific works of South Indian poetry, the Thirukural, it celebrates the third, most intimate, and most censored section of the Thirukural: the Kamattuppal, extolling female love and desire. Despite buying my own copy, I was often drawn to poetry aisles to peruse the book, until one day, I walked into the tail end of a conversation two women were having near the stacks, poised by Kandasamy’s translation, trailing off with, “…probably one of those Kama Sutra-type books.”

Even such a passing statement is sharply indicative of the kind of perception created about the book as a text from India, with long roots in Orientalised images of South Asia. Drawing on this observation, I mapped the poetry aisle in one of the biggest bookshops in Oxford, and found a history of empire coded into the shelves.

In a postcolonial world, the bookshop is as much an institution of power and influence as a school or a library; marketing within the bookshop can assert or subvert ideology, and often reinforces antiquated colonial beliefs about countries in the Global South. Stereotypes are often depicted through common and blatantly obvious colonial imageries of an exoticised and fetishised geography, emphasising certain aspects of its philosophy and art, including eroticism and transcendental spirituality. One sees a brief nod towards an elect niche of writers accepted within the white canon, whose work is considered the exception in Indian literature rather than the rule.

We could argue that the books of poetry available in corporate bookshops are heavily contingent on the logistics of import or export, or publishing to mass markets in the first place. In a previous comment I examined how marketing choices catering “to ‘local reader preferences’ consistently reinforced existing biases against postcolonial countries of the Global South”; so while we can offer some benefit of the doubt to market forces within the publishing industry, there is an overwhelming subconscious strategy that reinforces colonial stereotyping on bookshelves.

The overwhelming picture of South Asia in the poetry aisle is still exoticised, fetishised and emphatically depoliticised

In the poetry aisle one sees the specific ways the ideology of empire is reinforced by the choice of books displayed on bookshelves. In the bookshop in question, books are generally arranged in alphabetical order by last name of author. As a South Asian, my familiarity with books from the region let me map India on the shelves, following a pattern of Oriental imagery that was hard to miss.

From Afghanistan a single copy of Parwana Fayyaz’s Forty Names tells the story of a broken lineage of Afghani women. Amitav Ghosh’s Junglenama, an iteration of the legend of Bon Bibi from the Sundarbans, retold in his novel The Hungry Tide, sits next to Meena Kandasamy’s The Book of Desire. Again I Hear These Waters, a collection of translated poetry from the north-east of India, edited by Shalim Hussain, is resonant of folk and love poetry from Assam. Vivek Narayanan’s After reimagines the Ramayana, an ancient Sanskrit epic. Vikram Seth’s collected poems, and two texts of Bulleh Shah’s Sufi poetry and Rumi’s love poetry round off the collection of ‘South Asian poetry’.

What troubles me is not the texts themselves, for these are prolific writers whose poetry is imaginative, subversive, and — in the context of their origin — often deeply political and deserving of greater visibility in the literary landscape. But these titles and covers form a telling picture of South Asian poetry in a British bookshop. Publishing houses incur exorbitant costs to create covers and title visuals that attract readers precisely because people judge books by their cover. In the genre of South Asian poetry, the covers and titles as a whole are emphatically coded in a colonial praxis. The overwhelming picture of South Asia in the poetry aisle is still exoticised, fetishised and emphatically depoliticised.

The Book of Desire, I realised, was Meena K’s only poetry collection in the shop. Even the titles of her other works may be considered too inflammatory or niche. Perhaps that was it: a book entitled The Book of Desire spoke directly into the cesspool of imagery built around an Oriental India. The cover failed to mention that this book is a translation of the Thirukural; in the Indian edition, Thiruvalluvar takes his rightful place above Kandasamy’s name. Divorced from its origin as a Tamil text and placed squarely within the marketable category of "South Asian/Indian poetry", The Book of Desire now passes for a collection of erotic poems that can be referred to as a “Kama Sutra-type book” (with the appropriate Victorian derogation attributed to this text as well, whose rich poetry and philosophy has been steamrollered by a Western imaginary of Indian porn). And all this, when three pages into her introductory essay, Kandasamy writes about how she hopes this book isn’t mistaken for “a technical manual on how to reach an orgasm”.

Publishing houses and the industry at large make active efforts to promote diverse voices, mainstream different cultural contexts, and encourage dialogue across the world through literature. But the effort to diversify the literary landscape cannot be contained at the level of writing alone. It needs to permeate to the levels of the industry engaging directly with readers. This includes marketing in bookshops.

Countries from the Global South come with vast traditions of poetry harnessed to cultural, social and political causes. Superficial representation subconsciously emphasising colonial imagery in the present can be harmful to the project of inclusivity, representation and diversity that the book trade seeks to incorporate. We need to hire more people of diverse sensibilities in all areas of the industry, for it is such collaborative efforts that will enable a change in perception of global voices in the bookshop.