You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Naming the bias problem

I’ve been working at SAGE for nearly 30 years, yet I remember how I got my lucky break with unusual vividness. After graduating from Exeter University with a degree in psychology, I decided publishing might be the right industry for me. I thought, as it turned out correctly, that it was full of lovely, clever people doing important, interesting work. However, my enthusiasm took a beating over the following eight months as I wrote application after application without success. In fact, over that time I applied to over 100 publishers and was ignored or rejected by them all, except for a single interview (for a job I didn’t get).

In desperation I turned to my father for advice. He said, quite matter of fact, that the problem was my first name and that I should switch to my middle name, Paul. I was shocked at the suggestion, but pretty desperate by then after eight miserable months of applications while working in the Jackets, Coats and Suits merchandising department at Dorothy Perkins. So, I swallowed my pride and did so. Paul did far better than Ziyad had done. He made seven applications and got four interviews. I still remember sitting in the interview room waiting to be collected after finishing a pre-interview exercise on a children’s encyclopaedia. The interviewer came in and said, “We’re ready for you now, Paul.” It took me a while to realise he was talking to me, before red-faced and flustering I stood up.

Anyway, Paul was offered that job. At the same time, I also received an offer from SAGE. SAGE was the sole publisher who had given me an interview in the first batch of 100 or so applications, so when a second job came up there I re-applied (this time, succeeding) under my first name, assuming they would have me on file.

Faced with two offers, I encountered, in retrospect, a “Sliding Doors” moment. We know there are many twists and turns that shape a life but this was one concrete decision I remember that propelled me on a trajectory. In an alternate reality, Paul went on to work at Kingfisher Books while in fact I went to work at SAGE, as Ziyad.

Looking back, I don’t know why I was so shocked at my father’s suggestion. While publishing might make claims to being a fairly progressive industry, I had seen enough through his eyes, and received enough insights gleaned from a psychology degree, to realise that unconscious bias is rife in human judgements.

The academic literature on this makes particularly depressing reading when you consider what it tells you about how prone we are to implicit stereotypes and dodgy first impressions. However much we convince ourselves that we are fair-minded, evidence of many types shows we have deep-seated biases that colour our perceptions of each other. And because these are unconscious, we have little capacity to do much about it through sheer will. You can see for yourself by taking the Harvard Implicit Association Test online.

Diversity and inclusivity are issues that have had a lot of coverage recently across the publishing industry, and there is evidence of a real will to tackle the issues. My colleague Stephen Barr, in his recent term as president of the Publishers Association, focused on securing agreement to industry-wide goals which were incorporated into the 10-point Inclusivity Action Plan published by the PA.

The black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) population in London is up at around 30%, far higher than the numbers we see at SAGE today and across the industry. The reasons are many, and not all can be tackled from within any one organisation. But there are clearly things that are worth doing. My colleague Kiren Shoman has been leading our diversity working group for the past few years and has helped to ensure we have responded to the problem.

It’s particularly gratifying that we now anonymise applications by removing names and educational establishments, and assess our job descriptions and adverts for hidden assumptions. We also pay our interns. The work experience route is a long-established way of staff getting in to the publishing industry, but paying interns ensures that they don’t depend on having independent financial support.

Taking action

We are working with organisations that focus on increasing representativeness in the creative industries, including Creative Access, a non-profit that is helping young people from BAME backgrounds to secure paid training opportunities in the creative sector, and supporting them into full-time employment. We regularly offer courses around unconscious bias as well as inclusive management training, and are partnering with a number of universities that represent a diverse student cohort to help ensure publishing is a visible and inviting career option for them.

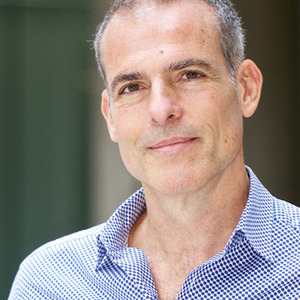

But we cannot be complacent. The challenges around inclusivity are deeply entrenched in our society and our industry, and will not vanish easily. I’ve had reason to reflect on this, and the ongoing relevance of my specific story, while completing my book Judged: The Value of Being Misunderstood.

I think there is something about being an immigrant (I was born in Baghdad to a Jordanian father and Irish mother) that has sustained my interest in the ubiquity of judgement and the many ways we can feel misconstrued. I’m conscious that my white (and male) face has prevented me from experiencing the daily indignities many people are forced to encounter, but the “Sliding Doors” incident with my name is a valuable reminder that ideals of equality and justice require constant effort, and are never to be taken for granted.

Ziyad Marar is the president of global publishing at SAGE. His book Judged: The Value of Being Misunderstood will be published by Bloomsbury on 22nd February.