You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

No flash in the pan

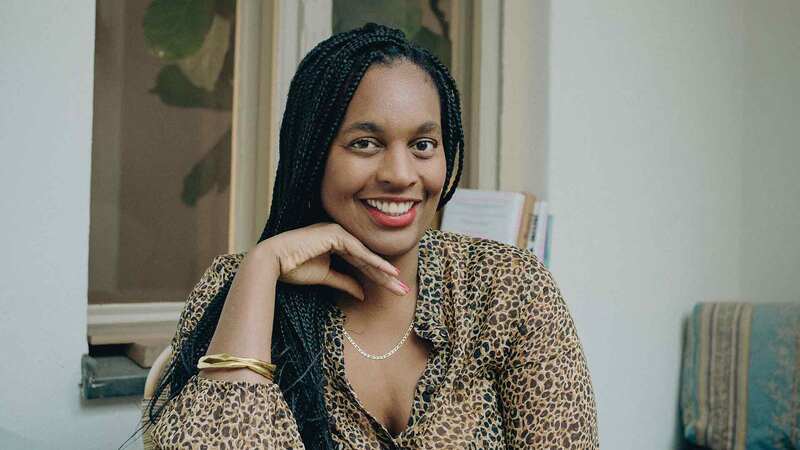

Having come up with the idea for a prize specifically for writers from working-class backgrounds, Clare Povey outlines how it has fared to date.

Picture this: I’m sitting in the Writers & Artists office in 2018, tapping away at my computer, feeling proud that I’ve just helped launch the first prize specifically for working-class writers like myself. It’s the stuff that every entry-level person in publishing dreams of—for your ideas to not just be heard, but actively supported.

But then the phone rings.

I answer, imagining it’ll be a typical call we receive: a writer looking for advice on how to take the next step in their career. We can end up on the phone for hours, talking a writer through the submission process or compiling a long list of resources. It’s all part of the incredibly varied, rewarding job.

But this call is different.

We’re not all on a level playing field. We never have been and we never will be, especially in creative industries where, according to recent research from the Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre, “only 16% of people in creative jobs are from working-class backgrounds”

“I’m calling to ask about this new prize of yours only for working-class writers,” the voice spits. “It’s discriminatory and divisive and you should feel ashamed of yourself.”

This person wasn’t interested in listening to my response, but if you ask me why I decided to create this prize, that telephone call sums it up.

We’re not all on a level playing field. We never have been and we never will be, especially in creative industries where, according to recent research from the Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre, “only 16% of people in creative jobs are from working-class backgrounds”, compared to almost a third of all workers across the entire UK workforce. This figure drops to as little as 10% for those working as authors, writers and translators, and 12% for those working in publishing. For those that make it in, “getting on” can be as difficult as “getting in”: almost 80% of working-class people surveyed by The Bookseller in 2019 felt their background had adversely affected their career.

I grew up in Chadwell Heath, a place that sits on the boundary of where east London meets Essex. Stories were an intrinsic part of my life, but a career in the arts felt unachievable. My comprehensive school was placed in special measures and teachers came and went, while budget cuts meant the elimination of career development programmes and other extracurricular opportunities. It was not only a period of great disruption, but a time when the arts was completely forgotten. Creativity became an afterthought, a luxury for other, luckier children.

This isn’t a unique story. I’m not the only book-loving kid that grew up with no knowledge of the publishing industry, but when I did eventually find my way to an entry-level job at Bloomsbury Publishing, I felt compelled to create opportunities for working-class creatives.

The entry criteria for the Writers & Artists Working-Class Writers’ Prize are simple. All we ask is that you are over 18 and are living in the UK or Republic of Ireland; submit a piece of unpublished writing; do not have a publishing contract or agent; and consider yourself to be from a working-class background. The winner receives a cash prize, mentoring from our judge, a W&A Guide To… book bundle, access to a number of our events and a year’s free membership to the Society of Authors. Our shortlisted writers also receive a book bundle and Society of Authors membership.

Some people bristle at the mention of self-identification. The semantics of defining class is something that academics have debated for centuries. We know that class is tricky to define and that we can’t talk about it without acknowledging the intersectionality of race, gender, disability and other factors. So why not allow the individual to decide if this prize speaks to them? We don’t pry or obstruct. There are enough barriers for working-class people as it is.

Our inaugural prize winner, Lucy Kissick, went on to secure literary representation and a two-book deal with Gollancz. Her début novel, Plutoshine, was published this year. The prize continues to grow and this year we are sending feedback to every writer who enters. It’s no easy feat for a small team, but it’s something we plan to offer for every year that follows. The prize should be more than just a flash in the pan: it aims to provide tangible, useful advice and next steps.

Previous judges for the Writers & Artists Working-Class Writers’ Prize include Natasha Carthew, a Cornish writer and poet; Paul Mendez, whose début novel Rainbow Milk chronicled the coming-of-age story of a young, gay, Black man fleeing his upbringing as Jehovah’s Witness; and Lisa McInerney, an award-winning Irish author who gives voice to the inhabitants of Cork.

The lives of working-class writers are incredibly varied, which is reflected in the enormous diversity of stories we receive. The entries range from historical to fantasy, contemporary fiction to memoir, and everything in between.

Imagination has no limits. And I won’t stop until the same is true for the careers of working-class writers.