You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

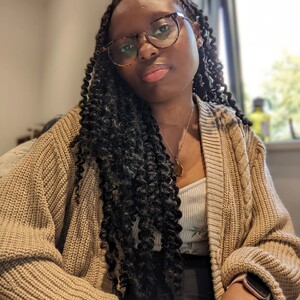

Of bad women and white privilege

Our hunger for books about white con women leaves a nasty taste.

Caroline Calloway’s first memoir, And We Were Like, was supposed to be published by Flatiron Books, an imprint of Macmillian, in 2016. Except it never happened, because it was revealed that Calloway had a ghostwriter write the proposal – and that she’d lied about her life too, the one that caused publishers to be interested in her in the first place.

Her second memoir, Scammer – Calloway’s attempt to respond to the comments against her – is self-published. Released to journalists this June, it has received positive reviews, despite the general public still not receiving copies after paying up to $65 each for them; although this detail feels unsurprising if you know of her past actions, such as having forged her academic credentials to get into Cambridge University.

So why do we give a known liar such attention and acclaim, let alone our money?

A dissection of influencer culture, and the blurred lines between Instagram and reality, is a whole other piece; but to see respectable book critics and readers still give Calloway attention is rather frustrating. After all, after having lost out on a $375,000 book deal from Flatiron and being outed as a fraud, you’d think that the media would agree not to take her seriously. Yet Becca Rothfeld at the Washington Post called the book “gloriously opulent”, while reviews and interviews have appeared in the likes of the Guardian, the Evening Standard, Vice and Rolling Stone. Kitty Grady wrote an entire article entitled "In Defence of Caroline Calloway" for Vogue in which she praises Calloway as a “deft and funny writer”. Really?

Feminist non-fiction has become increasingly popular, with readers clamouring to hear the details of the untold stories of women who have changed, and are trying to change, society.

Publishing thrives on trends. There are a wide array of memoirs available by women from all walks of life, discussing their unique experiences, although they’re often nudged into archetypes: The Activist who chained herself to embassy fences in the 70s, or The Online Journalist who discusses pressing social issues of our time, from sex and intimacy to the housing crisis, through a deeply personal lens.

I doubt that if R F Kuang or Zadie Smith were revealed to have faked their way into Cambridge and barely written a word of their books, they would be lauded as clever and rebellious

Of course, we want to know who these women really are. Authenticity is just as bankable as a curated persona, and we love to know the secrets and insecurities behind the public face. But there appears to be a growing fascination for women whose curated persona deviates so strongly from their true selves that it reaches the point of illegality and cruelty. Is that really something that deserves the spotlight of celebrity?

This is not exactly the only time women have had to put on masks for the sake of their careers, but The New Subversive – a woman who breaks the rules and sometimes laws – has taken on a particularly nasty flavour. She is not nice and so much of her is fake, but that is what makes her intriguing! She’s different! She breaks the rules because men do the same, so why can’t she?

Calloway is one of a growing number of subjects who manage to con their way to fame. Anna Delvey became widely known due to Rachel Williams’ book My Friend Anna: The True Story of the Fake Heiress of New York City, and Bad Blood by John Carreyrou details the rise of Theranos fraudster Elizabeth Holmes. I doubt either Williams or Carreyrou’s intention is to bring acclaim and further social capital to these con artists – but that appears to be the result.

And much of the narrative around these women has an edge of apology too. They are painted as victims of capitalism or hustle culture. They are dishonest, but their white womanhood seems to insulate them. Elizabeth Holmes defrauded investors, but she did it in a male-dominated industry, so… she’s a girl boss?

Calloway or Delvey are not the firsts, of course. Rachel Dolezal, infamous for masquerading as a Black woman, released a book with Penguin in 2017 – and has subsequently been charged with welfare fraud after she failed to report tens of thousands of dollars in income from her memoir, In Full Color: Finding My Place in a Black and White World.

I think of many of the Black and brown female writers I admire – who had to work hard to get into university and navigate an incredibly undiverse publishing landscape to get their books published. Somehow, I cannot see any of them receiving such lenient and exciting coverage from publishers, press and other writers. I doubt that if R F Kuang or Zadie Smith were revealed to have faked their way into Cambridge and barely written a word of their books, they would be lauded as clever and rebellious. Or that, if I wrote an entire piece in a national newspaper about how I cheated my way into an elite university, I would – nor should – receive high-profile book reviews and a cover story.

Exceptional behaviour and making yourself palatable to white audiences are how women of colour must navigate success. But white women in all arenas are not held to the same, sometimes absurd, standards. Of course, I am not arguing that I want Black women who are scammers or liars to receive acclaim. But I cannot help but see the double standard; both in the insistence that Black female stories be relentlessly heroic and in the strange lionisation of white female charlatans and grifters.

It’s just one example of how an industry that is supposed to reward creativity and authenticity seems to be more concerned with what generates buzz and clicks. When we distance ourselves from the supposed intrigue and glamour of these stories, we realise that their protagonists are not victims or creative. They are just liars – and rather bad at it, to boot.