You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Opera opportunities

Novels have long provided rich inspiration for operas. Will The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas translate?

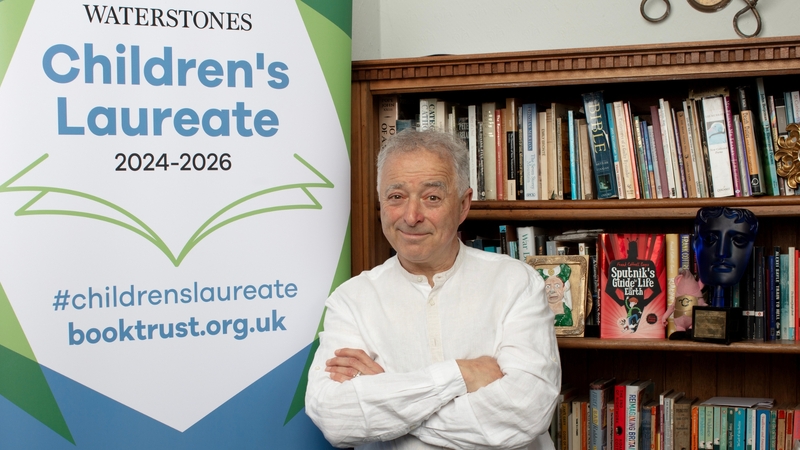

"A Child in Striped Pyjamas" is a new chamber opera by Noah Max based on the hit book The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas by John Boyne.

The novel charts the friendship that develops between Shmuel, a Jewish child imprisoned in a concentration camp and, Bruno, the son of a high-ranking Nazi, during the Second World War. Despite its huge popularity – it has sold around seven million copies — Boyne’s novel has proved divisive, with some arguing its fable-like approach could prove damaging to people’s understanding of the horrors of the Holocaust. At one point, Boyne ended up in a social media spat with the Auschwitz Museum.

Nonetheless the book has proved fertile ground for adaptation. In addition to the 2008 movie version written and directed by Mark Herman (interestingly, the opera is billed as being presented "in special arrangement with Miramax") there has also been a ballet version of the story. Max’s opera, which will premiere on 11th January at the Cockpit Theatre in London, is just the latest and it’s easy to see why the emotive story would appeal to a composer.

Opera composers have long drawn on literary sources. Some of the best-known works in opera draw on novels or novellas. George Bizet’s "Carmen" is based on Prosper Merimee’s 1845 novella. Donizetti’s "Lucia di Lammermoor" is inspired by a novel by Walter Scott, The Bride of Lammermoor. Puccini’s "La Boheme" is based on Henri Murger’s Scenes from Bohemian Life.

There has been a Great Gatsby opera, a Grapes of Wrath opera and a Moby Dick opera. There have been operas based on Graham Greene’s Our Man in Havana and The End of the Affair. There has even been a Tristram Shandy opera.

Opera as a form lends itself to spectacle and heightened emotion — more so perhaps than a theatrical adaptation — and opera companies often have the kind of financial resources that further enables the translation of an authorial vision to the stage

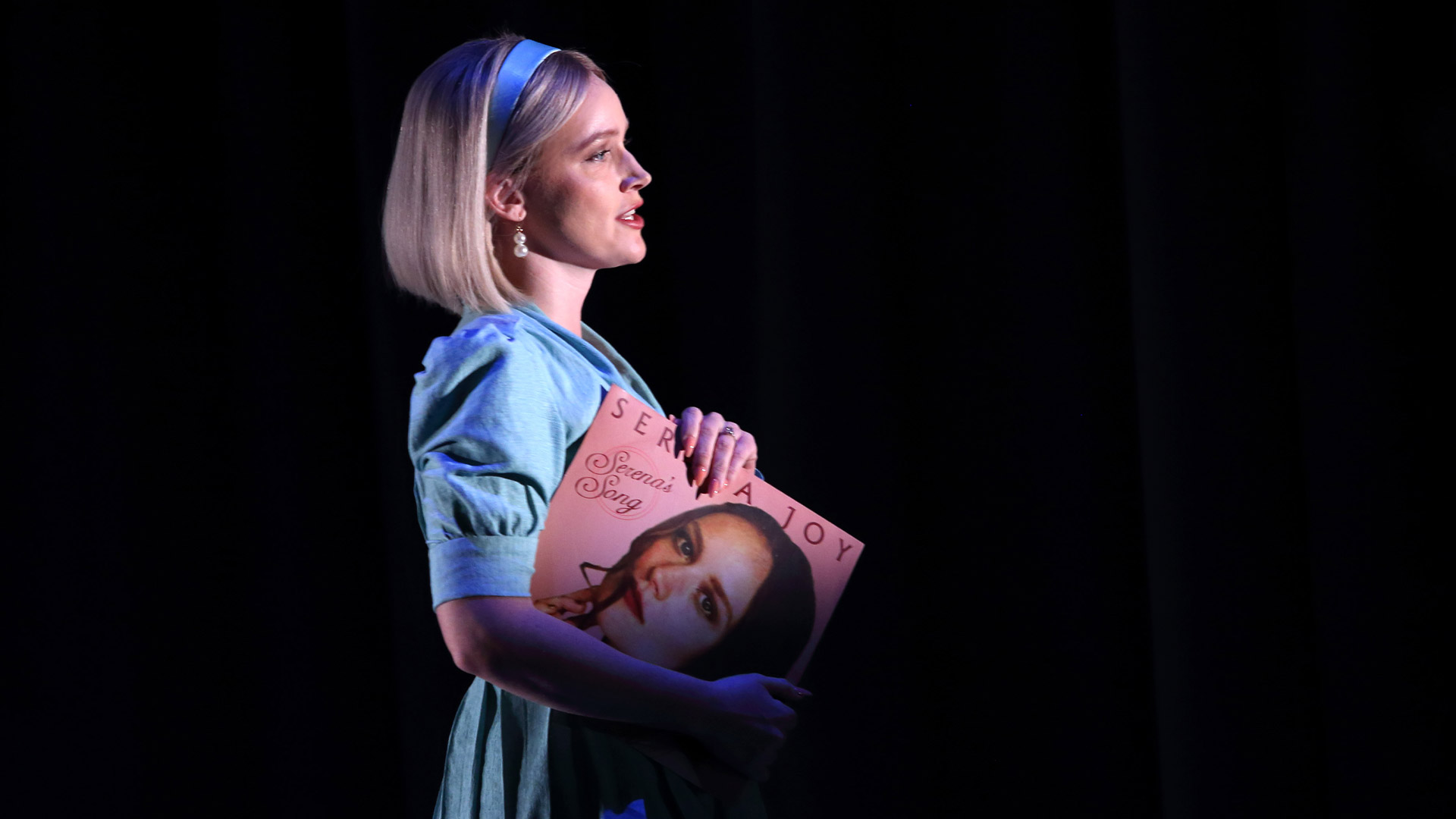

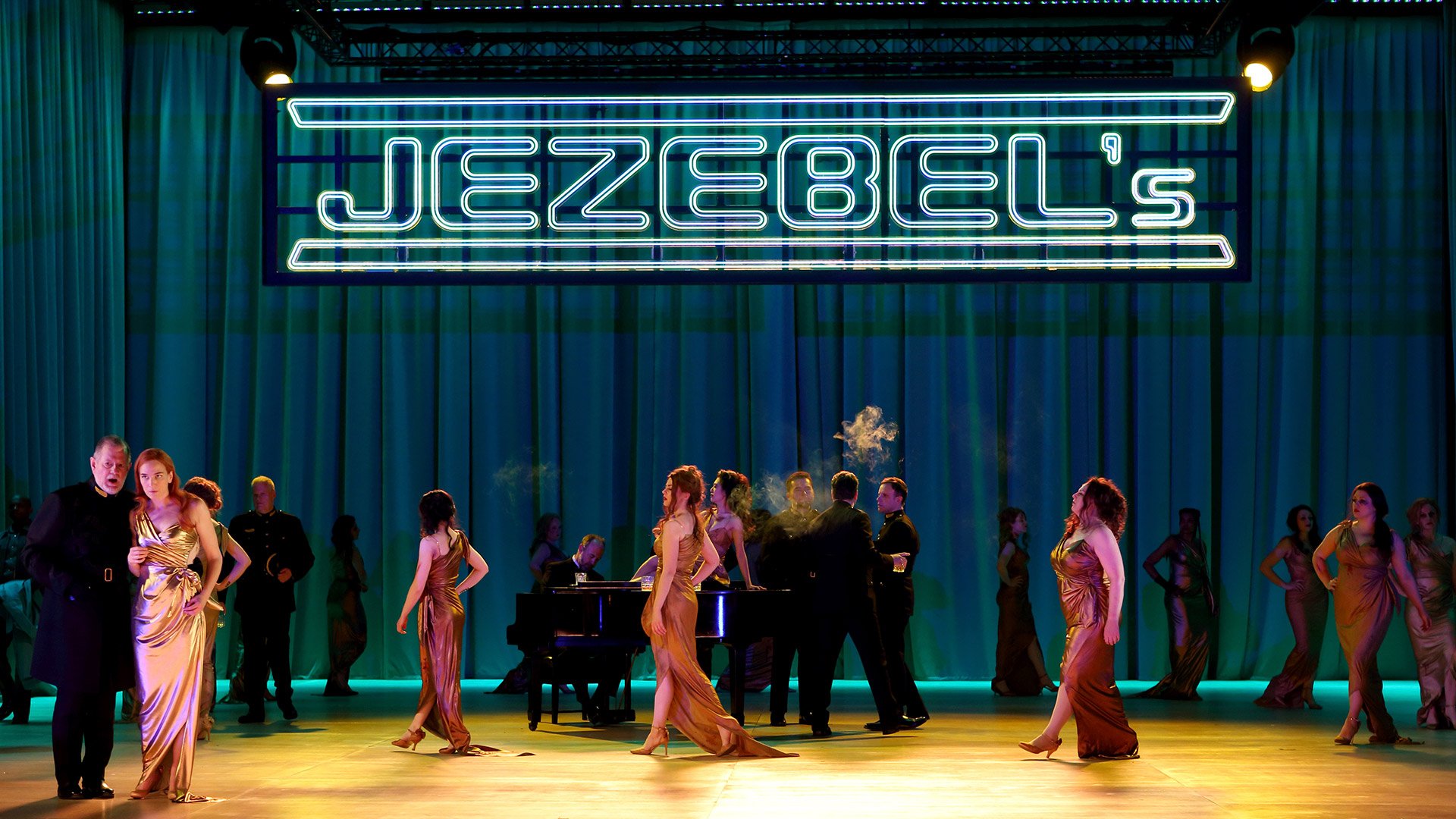

In recent years there have been several notable operatic adaptations of contemporary novels. Ages before the harrowing TV show based on Margaret Atwood’s depressingly prescient The Handmaid’s Tale made it to our screens, there was an opera version, by the composer Poul Ruders and librettist Paul Bentley. It premiered in Copenhagen in 2000 and was staged by English National Opera three years later, directed by Phyllida Lloyd. The opera deviated from the novel structural using the symposium on Gilead, a postscript in the novel, as a framing device.

A revised version directed by ENO artistic director Annilese Miskimmon was staged at London Coliseum in April last year. With the repealing of Roe v Wade only two months later, it felt horribly timely. The production was also notable for its all-female creative team, a rarity in opera, and the stage was filled with women in the now iconic red smocks and white visors. The critical reception was somewhat mixed, however, with Nicholas Kenyon in the Telegraph calling it a “brave new staging,” while the Guardian’s Erica Jeal argued “If ENO wants to stage a real feminist opera it needs to look further, to more recent works, but this is at least a step in the right direction.”

By way of contrast, in 2013, Opera North presented a version of Philip Pullman’s children’s novella The Firework-Maker’s Daughter, a co-commission with the Royal Opera House and the Opera Group. The chamber opera by David Bruce with a libretto by Glyn Maxwell drew on Pullman’s story of a young girl who dreams of becoming a firework-maker. While opera is often thought of as lavish, the production won praise for its use of overhead projectors to create the special effects.

American bestsellers have inspired a number of recent operas. Charles Frazier’s sprawling American Civil War novel Cold Mountain – also the basis for the Anthony Minghella film starring Kate Winslet and Jude Law – was turned into an opera in 2015, receiving its premiere in Santa Fe. Steven King’s 1992 novel Dolores Claibourne was the basis for an opera by Tobia Picker. It received its premiere in 2013 and a new chamber version was presented in 2017 at New York’s 59E59 Theater.

Dolores Claibourne, about a woman suspected of murdering her wealthy employer, also resulted in what I would argue is one of the best screen adaptations of King’s work – Taylor Hackford’s 1995 film starring a never better Kathy Bates and Jennifer Jason Lee as Dolores’ daughter. That both of these were also popular films is perhaps telling.

Artists constantly draw on stories with which we are already familiar, that have already cemented themselves in the culture, using different tools — in this case, music — to tease out different narrative aspects and present them to different audiences. Opera as a form lends itself to spectacle and heightened emotion — more so perhaps than a theatrical adaptation — and opera companies often have the kind of financial resources that further enables the translation of an authorial vision to the stage. It will be interesting to see whether the opera based on Boyne’s novel can cast the same spell as the source material did for so many.