You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Our 'intense' meeting to decide Dylan Thomas shortlist

If ever there was a literary award demanding to be one for all types of genre and for all kinds of size and intent, then surely it is the International Dylan Thomas Prize from Swansea University.

Thomas–dead in all his glory at 39 in 1953–was a ‘show me what you’ve got’ writer who burst like a rocket-fuelled teenage projectile out of the suburban rectitude and dullness of his native “ugly-lovely” town of Swansea to alarm the metropolitan complacency of pre-war London, and he carried on, flaring away, in post-war New York City until his genius was extinguished by self-administered alcohol and mal-administered medication. In between there were stories, comic and plangent, glinting novellas, enchanting screenplays, resonant documentaries, breakthrough drama for a new age, essays and memoirs, letters for the passing moment, and poetry for forever.

What distinguished him during his short lifetime, and marks out this eponymous prize for writers in English worldwide who are 39 or under, is writing so innovative it dazzles, and literary intent across a variety of forms which is so bold that it insists on being read again and again, generation by generation. Nothing so irredeemably foolish then, in him or in the prize for which I act as chair of this year’s judges, as any kind of plodding comparison of novels with verse or short stories or anything else. Weighing thistledown against granite only gives you a measurement, never a judgement.

So, we asked, instead, how thrillingly good was one writer's concept and execution against another's equally valid stand-alone achievement. Would this particular book call you back to read it again? Did a writer do something, and so well, that it made you gasp or sing out in praise? Did a manner of structure and its writing reveal, or perhaps betray, a profundity of subject matter? Together we trawled for undoubted excellence and if, here and there, we detected a flash of Thomas’ daring or a glimpse of his hard-won unity of the specific and the universal, well, then, hey, we applauded.

Amongst the six of us who read the brilliant, eclectic longlist of 12 books, are novelists, poets, theatre practitioners, literary critics, and some who have dabbled in more than one literary stream. Our meeting to arrive at a shortlist of six volumes was intense, arduous and genially disputatious. The result, I believe, would have pleased the self-styled Rimbaud of Cwmdonkin Drive, Uplands, Swansea. Humour and tragedy, in reflection and as playfulness, dance through our selection of fiction and verse. They are all winners in their own right. So much so that I am not at all sure how we will pick a single prize winner in May. But, for sure, to do so will be both fun and a privilege. Whatever the decision we ultimately make, I’m confident that it will truly honour Wales’ foremost expressive twentieth century writer, Dylan Marlais Thomas, and, like him, it will catch the world’s attention.

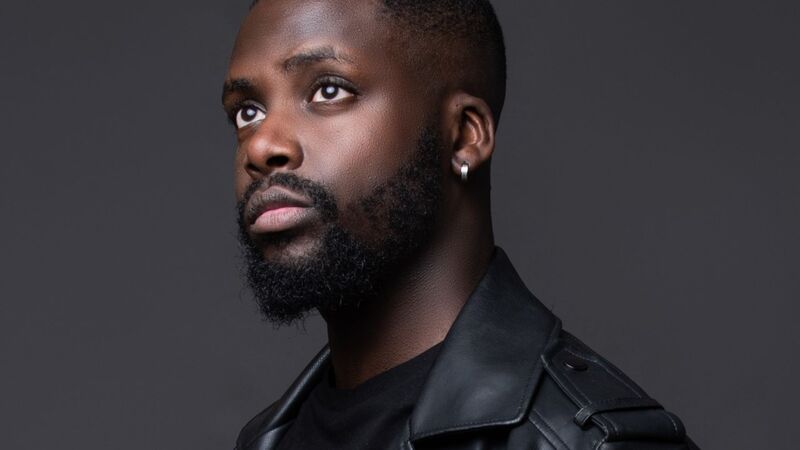

Professor Dai Smith is Raymond Williams research chair in the cultural history of Wales at Swansea University.

Picture: Darren Britton