You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Prize politics

What do this month’s award-winners tell us about the literary landscape?

It’s that time of the year again!

In the publishing industry, November is always eagerly awaited: it is the time of literary awards. From the Booker Prize in Britain to the prestigious Goncourt award on the other side of the Channel, who gets what plays a crucial part in sales and trends over the upcoming year.

In 2024, however, awards in France and Britain went to books that could not have been more different.

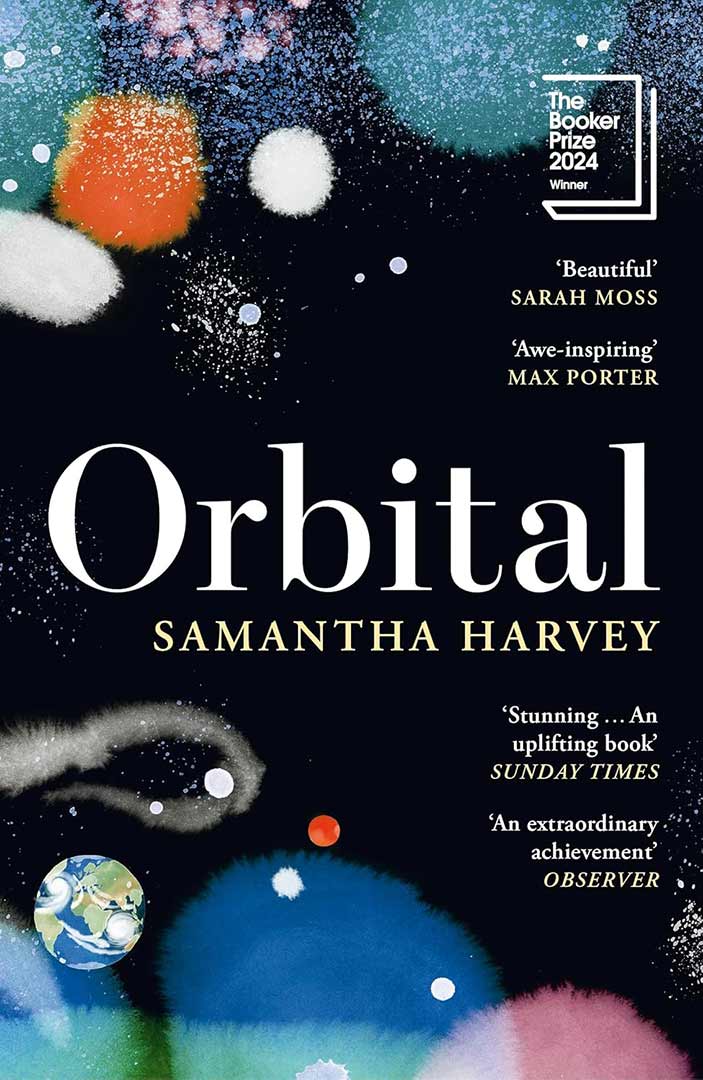

The 2024 Booker Prize was awarded to Samantha Harvey for her “space pastoral” Orbital—the meditative story of a crew of astronauts who, from their station orbiting the Earth, witness 16 successive sunrises over a span of 24 hours. The novel has been called “ethereal”, “mesmerising” and “beautifully poetic”.

At the other end of the spectrum, the Goncourt went to Kamel Daoud for his novel Houris. It is the story of a woman, Dawn, who lost her voice as armed men cut her throat and slaughtered her family during the Algerian civil war. Her vocal cords are damaged beyond repair, and she is marked for life with a smile-shaped scar across her neck. While pregnant, she tells her unborn child the story of her life—an account strewn with madness and atrocities at every corner.

It is worth noting that the other favourite for the Goncourt prize was Gaël Faye, whose second novel, Jacaranda, explores an equally dark area: the genocide in Rwanda, which Faye witnessed first-hand as a child growing up in Burundi. On the same day Daoud received the Goncourt, Faye was awarded the Renaudot prize, a slightly less media-friendly but equally prestigious honour.

In an increasingly insecure world, these choices reflect the need for something dramatically new, something only fiction can offer: hope.

It might look like there is strictly nothing in common between a poetic space odyssey on the one hand, and several accounts of political unrest on the other. I suggest, however, that in an increasingly insecure world, these choices reflect the need for something dramatically new, something only fiction can offer: hope.

These three novels are bound by a firm belief in humankind. In Orbital, seeing the world from a distance makes political quarrels irrelevant, as the Earth’s frailty is revealed. This is a feeling reported by many of those who have been into space, including 93 year old "Star Trek" superstar William Shatner. In space, astronauts from all nationalities live side by side, sharing concerns for their families, in awe before the beauty surrounding them, and thinking alike in an almost mystical cohesion.

In Houris and Jacaranda too, hope lies in the human ability to get beyond conflicts that seemed impossible to surmount. Despite her past, Dawn brings her child into the world—an act of hope and trust if there ever was one. Milan, the main character in Faye’s novel, explores his family’s covered-up story during the years of the genocide, showing that knowledge and understanding can be the first step towards resilience. Paradoxically, in spite of their heavy subjects, both these books appear luminous.

At a time where opinions across the political spectrum are becoming ever more rigid, those are books that include everyone in the conversation and refuse to tell us what to think. This alone is a remarkable achievement.

Does this mean the current trend in literary prizes is now vanilla-flavoured good intentions? Quite the opposite. Writing these texts took courage on the authors’ part: in Algeria, where written works focusing on the civil war are strictly prohibited, Daoud’s publisher Gallimard was prevented from attending the Algiers book fair, as Houris was banned in the country. A few years ago, Daoud himself was the target of a fatwa after he criticised the religious regime in place in Algeria. Houris is a perfect example that unearthing forgotten stories takes courage, even—or maybe especially—if you are offering a glimmer of hope.

In a similar fashion, on awarding Samantha Harvey the Booker Prize, the jury said they appreciated how the book was “not finding answers but changing the question of what we wanted to explore”. In an increasingly extreme public debate, putting things in perspective beyond partisan views and sectarianism is essential. What the Goncourt, Booker and Renaudot prize winners have in common this year is the literary and intellectual courage of taking the road less travelled.

As many people feel we are reaching the end of a political, societal and ecological cycle, it becomes clear we need to re-invent the way we think and live. This year’s awards show us there is no scarcity of fresh ideas in the literary world. As we need to re-invent our lives on so many levels, fiction is offering us the possibility to think outside the box and reframe what we thought we knew by heart. This is why it is urgent our political leaders start reading fiction again—and it’s not just me saying it.

This is why, if you really want to make a difference, I suggest you ditch Machiavelli’s Prince and re-read your favourite fiction instead—be it Orbital, Jane Eyre or The Very Hungry Caterpillar.