You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Publishers need to read fan fiction

There’s more value in fandoms than you think.

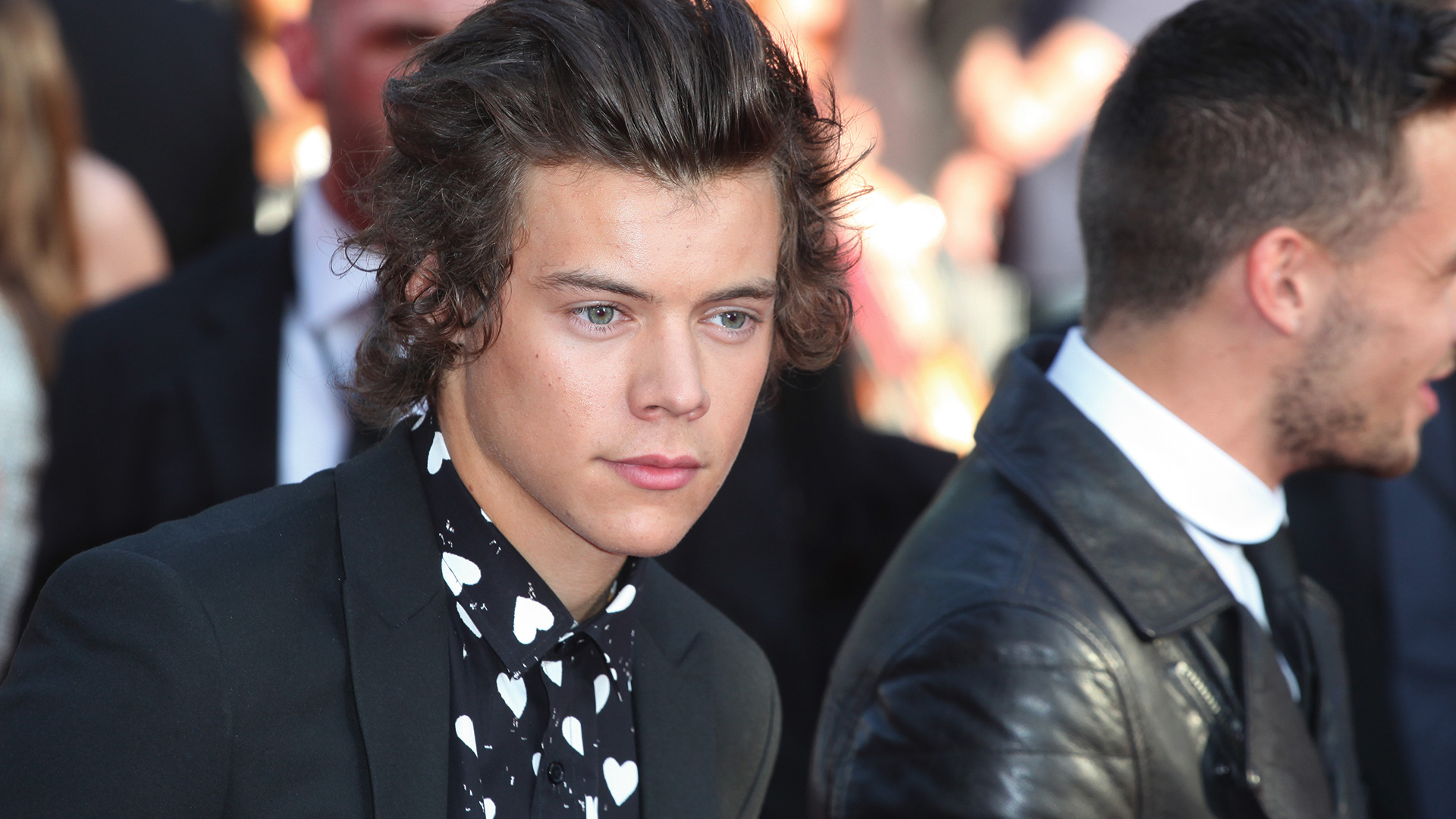

Let’s face it, when most people hear fan fiction, they picture teenage girls penning poorly edited stories with Harry Styles as both lead, love interest — and almost every other character. And that is one side of fan fiction: a celebration of fandom culture, an unabashed opportunity to invest in fan service or even to try out a new hobby.

But it’s also far more than that.

Back in 2009, the rise of the internet ensured that fan fiction was more accessible than ever before. Sites like AO3 and Wattpad were in their infancy, but communities were rapidly being assembled: teams of editors, beta readers and proof readers which, in many ways, mimicked the traditional publishing industry. But, fan fiction had the ability to move far faster than the industry, and was much better at embracing change.

From recruiting Brit-pickers — English editors that reviewed works for location-specific slang and spelling — to sensitivity betas, works were being examined for lived experience to ensure a truly immersive read. At the time, this was far more common in fan fiction than in the publishing industry. Most of these editors were also writers, taking every opportunity to test new ways of editing. You could jump on a forum and watch, in real-time, as editorial teams and writers crowd-tested chapters, with audiences feeding back their thoughts, and writers rapidly reworking unlikeable characters and clunky dialogue. Fan fiction, by its very nature, thrives on transformation and innovation.

And, years on, traditional publishing is only just beginning to learn the ropes.

It seems a surprise that a site depicting Draco Malfoy and his — fairly graphic — love affair with an apple has far clearer guidelines than Europe’s publishing houses

One staple of fan works comes in the form of tagging and labelling tropes. Audiences could choose from their favourites — from "enemies to lovers", to "side character love triangles" — ensuring that they got exactly what they were in the mood to get. Readers loved it and the publishing industry took note, and you can now regularly spot tropes being used as a marketing tool for titles across a variety of genres and categories.

As well as selecting your trope of choice, fan fiction also offered their readers crystal clear content warnings. The effectiveness of trigger warnings are clear in fan fiction; they’re also easily accessible, with the option to drop down a full list for the reader to make an informed choice. And while they appear to be a contentious topic in traditional publishing, young adult readers now rely on "Book Trigger Warnings" — a crowdfunded Wiki database that offers readers a guide to the more challenging themes in books, with one of the most popular categories being that of young adult titles. It seems a surprise that a site depicting Draco Malfoy and his — fairly graphic — love affair with an apple has far clearer guidelines than Europe’s publishing houses.

There are other learnings we can take from fan fiction’s reader-first approach. Harking back to Dickens’ days of serialised fiction, many fan fiction writers cultivate a community by releasing their work chapter by chapter. In a world of rapid content binges, this demonstrates that there’s still value in slower creation, and there’s still plenty for the mainstream industry to capitalise on. BookTok’s die-hard communities could discover a new kind of read-along, with readers tuning in for weekly updates, supported by behind-the-scenes content. This has the potential to create a digital community exploring literature in a way that we haven’t seen on a huge scale for generations, and the slower pace of this approach is also perfectly timed with a nostalgia for a simpler way of life, one that combines current technology with old-fashioned values.

But, unlike fan fiction, publishing is a business, one that has to weigh up every decision in a way that online communities writing under pseudonyms don’t. Traditional publishers simply can’t take fanfic levels of risks. But recruiting fan fiction writers to their lists can be a very smart route to success.

Most people know that the Fifty Shades of Grey series was actually a Twilight fic published on FanFiction.net, but they might not be aware that Aiden Thomas, bestselling author of Cemetery Boys, got his start in fan fiction. Another YA staple, Rainbow Rowell, is also well known for her "Drarry" fan fiction which went on to inspire both Fan Girl and her Carry On series. You might also recognise Cassandra Clare — a fan fiction darling for her Harry Potter fics — who went on to pen a bestselling series The Mortal Instruments. As well as Anna Todd, who penned the After series over on Wattpad.

These are just a handful of brilliant authors that have emerged from sites like Wattpad, AO3 and FanFiction.net — but it’s still rare to hear of editors trawling fan fiction sites for new talent, despite them hosting stories garnering millions of views from writers with a real gift for characterisation and not to mention, lived experience. Things are improving slowly now but back in the early 2000s, representation for many marginalised groups was virtually absent from the mainstream. Fan fiction readers had the opportunity to engage with their favourite stories — rewritten to not just represent them, but actually centre them. And a quick scroll through TikTok (and the many Wattpad and AO3 links) shows us that a brand new generation is discovering the power of fan fiction, too.

If a story born from a meme about a villain and his apple can create a series with over a million reads on Wattpad, we have to remember that there’s value in untested, strange and often slightly unhinged art.

We just need to be willing to read it.