You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Rethinking digital lending

Hachette may have beaten the Internet Archive – but the war on online-sharing is far from won.

The recent ruling against the Internet Archive (IA) in the Hachette v. Internet Archive case signifies more than just a legal defeat for the IA – it raises important questions about online sharing and public access to literature.

The core of this case revolves around Controlled Digital Lending (CDL), a practice by which the Internet Archive lends out digital copies of books it physically owns, one at a time, to a single user. It has become a battleground for copyright law, with publishers like Hachette leading the charge to shut down such efforts.

The IA claims that this practice extends a library’s traditional role of lending physical books into the digital age. Libraries have always promoted literacy and education, providing access to literature for those who might not be able to afford it. The IA argues that its model is essentially the same – except using digital methods to reach millions more people. So why are publishers so resistant?

At the heart of the resistance is, unsurprisingly, a concern over the lack of payment – for both publishers and authors. However, supporters of the IA believe that this concern must be set alongside the immense value digital libraries bring to communities worldwide, particularly in poorer regions. For millions of people in developing countries – or even within marginalised communities in wealthier nations – buying books is often a luxury they cannot afford, and libraries are not accessible. This is where digital platforms step in.

In this context, rather than clamping down on platforms like the IA, I believe that publishers should explore ways to engage with these readers, with the aim of turning them into paying customers wherever possible.

We can learn lessons from piracy here. Many publishers see it as a scourge that must be eradicated. However, piracy is an inescapable part of the digital age, and no matter how many legal actions are taken, people will continue to find ways to share content.

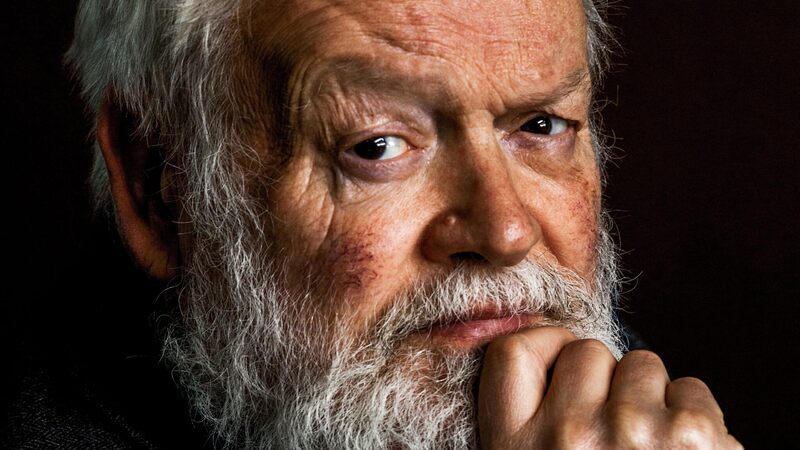

After all, Brazilian author Paulo Coelho famously embraced piracy as a way to expand his readership. When his books were pirated, instead of trying to stop it, he supported the practice, realising that it brought his work to new markets and audiences. He famously remarked that “piracy is your first contact with an artist’s work. If the idea is good, you’ll be happy to have it in your home; a consistent idea doesn’t need protection. The rest is greed or ignorance”.

The result? His sales soared. People who had pirated his books in regions where they couldn’t afford them later became paying customers. Coelho’s experience offers a powerful example of how publishers might think differently about online sharing – not as threats to be fought at every turn, but as opportunities to be harnessed.

Free digital lending such as CDL could open a route to many new licensing models, from freemium to advertising-supported

And what about out-of-print books? They may no longer hold commercial value but remain important for research and education, in which case they could find new life in the digital realm.

Of course, authors need to earn a living, and publishers need to be paid. But free digital lending such as CDL could open a route to many new licensing models, from freemium to advertising-supported. This model has been successfully used in other industries, such as music and gaming, where free access to content is monetised through ads or by offering premium, paid experiences. The data generated from digital lending could also be valuable in identifying reader preferences, helping publishers tailor marketing campaigns, identify trends to commission around, or decide which out-of-print works to revive based on demand.

A further benefit of digital distribution is the potential to experiment with flexible pricing. Rather than adhering to a one-size-fits-all pricing model, publishers could adjust the cost of access based on region, market demand, or even the nature of the content. Once a strong reader base is established, publishers could introduce paid options, such as special editions, print-on-demand services, or exclusive access to new releases. This strategy allows publishers to cultivate loyalty and engagement with readers who might not have been able to purchase books at full price, but would be willing to pay for other services or products later on.

The reality is that copyright law has not yet fully adapted to the digital age. Just as libraries once had to adapt to the introduction of new technologies, so too must copyright evolve to reflect new technological realities – as well as ensure that literature remains accessible to all in a rapidly changing world.

There’s an opportunity here. Instead of fighting against platforms like the IA, publishers can collaborate with them. As Paulo Coelho showed, there’s more to gain from embracing the new than clinging to the old. The court ruling against the IA may have been a temporary victory for publishers, but the real battle – over the future of access to knowledge, and the unstoppable force of digital sharing – has only just begun.