You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Revolution: writing for the nation

Wales has recently celebrated the centenaries of four notable writers: Dylan Thomas, T Llew Jones, Alun Lewis and Roald Dahl. Was there something in the air at the turn of the 20th century?

These are some of the best of Welsh writers, in Welsh and in English. They didn’t know each other and were probably scarcely aware of each other - but, through the lens of time, one can see interesting similarities: the influence of Welsh stories and legends on the English language poets, the delight in adventure and mischief in the children’s authors. Two of them are international literary stars and are, by now, successful global brands. The other two, although wonderful writers, have not achieved that level of celebrity.

It is notable that all of them can be regarded as unique voices, standing apart from the British colonial literary tradition. Although both Dylan and Dahl enjoyed international popularity, they received little acknowledgement initially from the English literary establishment. Both were lauded in the US long before England caught on to their talents. Welsh language school children are still familiar with T Llew Jones, and Roald Dahl is very popular with Welsh-speaking children thanks to the high-quality translations. For many, Fantastic Mr Fox will always be Mr Cadno Campus.

It is surprising that the work of Alun Lewis is not better known. He is not widely studied at secondary schools, which is a great shame. What surprised me too is that the work of Dylan Thomas is not popular in schools. When planning his centenary in 2014, I realised that New Yorkers are far more familiar with his work than the Welsh, and that schoolchildren in Ireland and in Germany are more likely to have read him than those in Wales.

We can’t let these significant voices be ignored or overlooked. If these writers are not included in the curriculum, then the efforts of organisations such as Literature Wales to focus on their work will be wasted. Generations of Welsh people are in danger of being denied their own literary heritage.

As well as education, publishing plays a crucial part in keeping our literary heritage alive. The Library of Wales series, published by Parthian with Welsh Government support, includes a wide range of English-language writers from Wales - from Raymond Williams to Margiad Evans - who might otherwise be out of print. Parthian, alongside many other independent Welsh publishers, also play a role in nurturing the literary talents of Wales, many of whom go on to become internationally renowned writers, such as Cynan Jones and Owen Sheers.

For those who had Welsh medium education, many eminent 20th century writers are familiar, including Waldo Williams, T H Parry-Williams, R Williams-Parry, Kate Roberts, Gwenallt and Caradog Pritchard.

These writers encompass an exciting and conflicted time in Welsh political life which formed part of an awakening of national awareness and identity. One of the most significant nationalist events of the 20th century was the Tân yn Llŷn – the Fire in Llŷn, in 1936 - when the Ministry of Defence’s bombing school in Penyberth was set alight, in a symbolic act of defiance, by three prominent writers: Lewis Valentine, Saunders Lewis and DJ Williams. In the years following this, other prominent Welsh language writers took to protesting and activism, and this was reflected in their literary works. It is difficult to separate 20th century Welsh language literature from its political landscape.

As in the past, these are troubled times, in Wales and across the world. As I write, opinion polls are predicting a political earthquake in Wales. Brexit, and the precarious international situation, led to concerns about the future of Wales and our identity as a country with a distinctive language and culture. Are there radical and actively engaged voices amongst our contemporary writers, as there were in the middle of the 20th century?

There is a new generation of poets and writers emerging who are up for the challenge. Sophie McKeand, the Young People’s Laureate for Wales, responded to last year’s referendum with Instagram poems entitled #100DaysofBrexit. With Literature Wales funding, Sophie and the poet Patrick Jones have been running workshops with school pupils on Fake News, encouraging them to response creatively and critically to articles in the mainstream UK press.

The young writers Grug Muse and Miriam Elin Jones are challenging the status quo of the Welsh language poetry establishment (in the main: male, cynganeddol, rooted in the Eisteddfod tradition) and writing lively, impish blogs on a range of subjects. Together with Llŷr Titus and Iestyn Tyne, they have set up Y Stamp, a magazine offering an alternative platform for Welsh literature. In addition, we now see an increase in live literature events across Wales which reflect diversity: feminist, LGBTQ+, and refugees.

By the time you read this, the general election will be almost upon us. Who knows what the position in Wales will be but there may well have been a shift in the political landscape. The concern is that communities across Wales have been neglected for generations. Too often, they do not feel a sense of belonging and they have been deprived of their Welsh heritage. We do not have our own voice in the press and, unlike Scotland, our political identity is less evident. There is such a scarcity of voices speaking on behalf of, and representing, the experiences of our communities and our most vulnerable groups, will the writers and artists of Wales stand up and be counted, will they lead the charge?

The poet Gil Scott-Heron sang “The Revolution will not be Televised”, and this was echoed in the electro-dub group Llwybr Llaethog’s record “Fydd y Chwyldro ddim ar y Teledu Gyfaill”. In his seminal lecture Tynged yr Iaith (The Fate of the Language) Saunders Lewis claimed that “trwy ddulliau chwyldro yn unig y mae llwyddo” (success comes only through revolutionary methods). Are we on the verge of a new revolution?

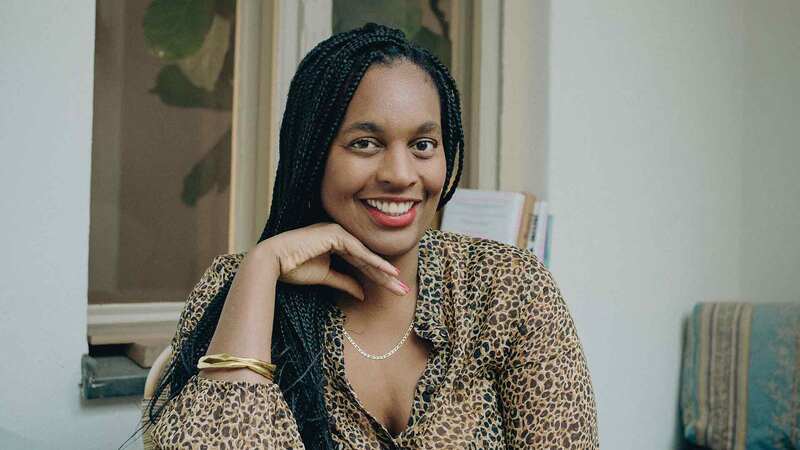

Lleucu Siencyn is chief executive of Literature Wales. A Welsh-language version of this column was published in The Bookseller, 5th May.