You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Same old stories

Is it time to put the trend for literary retellings to bed?

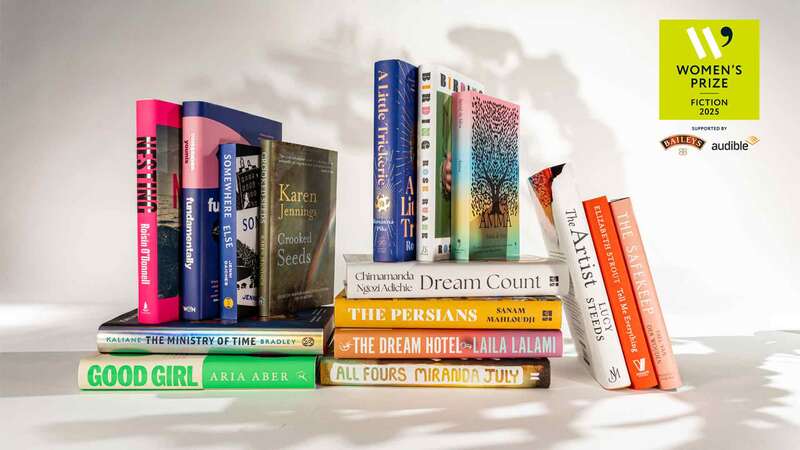

Literary retellings of classics have exploded in the past few years, not least thanks to BookTok’s enduring love for Madeline Miller and her feminist takes on the Greek myths. Reworkings and updates of well-known novels, myths and legends combine familiarity and freshness in a way that seems to load the dice for commercial success, from beloved old Bridget Jones (a take on Pride and Prejudice) to A Thousand Ships by Natalie Haynes, which takes the tale of the Trojan War and gives readers the view of the women involved. It’s extending to TV and film as well, with the likes of “Bridgerton” and “Mr Malcolm’s List” injecting Austenean tropes with fun, modern and inclusive twists.

Telling old stories in new ways is certainly a powerful way of engaging people with classic books, especially for teens struggling to connect with the curriculum. These novels are often complex and beautiful in their own right, opening our eyes to aspects of the characters that can be overlooked or ignored. A Thousand Ships makes the Trojan War much more than a group of men fighting for their right to claim a woman. Helen of Troy has a voice, Cassandra has a voice, and the goddesses have a voice. Women’s perspectives and experiences are restored.

Personally, literary retellings is a genre I find myself always reaching for. I love Little Women, but really enjoyed Marina Hill’s Little Writer, a retelling that imagines the March sisters as Black women in the North during Civil War America. Retellings can allow those of us who have long been underrepresented or negatively represented in publishing to retrospectively claim space and imagine ourselves in iconic story shapes, from Chloe Gong’s These Violet Delights, a "Romeo & Juliet" retelling set in 1920s Shanghai, or Peter Darling by S AChant, a queer, transgender take on Peter Pan.

Should publishers focus on... stories that have the potential to become the classics of the future, as opposed to churning out the same settings and plots told in numerous different ways?

But this vogue for new takes on old tales isn’t uncontroversial. Many of these original books were written by white, cis, straight and financially privileged authors, some of whose views or lives were deeply problematic. Are these popular retellings really just giving them more attention, when there are so many new authors whose new, original fiction deserves a platform instead? Should publishers focus on giving budget and time to a diverse range of authors with stories that have the potential to become the classics of the future, as opposed to churning out the same settings and plots told in numerous different ways?

Tracy Stewart, author of The Glass Key trilogy, is a fan of literary retellings, arguing, "They are a way to bring relevance to older stories for a modern audience. It also offers an introduction to the original classic work and its author so that a new audience can enjoy it. Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingslover is the perfect example of doing just that."

Kallia Papadopoulos, founder of Books Galore, a book reviewer and blogger, agrees that retellings are always great for opening a reader’s eyes; “I think they are great as they give a different perspective on an old-age narrative. They open up stories to a whole new audience. I like a balance where they mix the two; and bring similar elements into the current scene.”

But book blogger Charlie Rosse (known as The Romaning Reader to her followers) says: “The stories of the characters in the retellings have already been told; they have already had their moment and already received the coverage they cried out for. There are plenty of fresh stories that need the space that retellings take up.”

She is also rather cynical about the trend, arguing that it seems: “Like a lazy attempt to profit from well-known books/characters with the least amount of work, a mere money-making scheme rather than actually benefitting our modern literary scene.”

That argument is an incredibly compelling one. There are so many authors who write unpublished books that could be pushed aside because a retelling appears to be more compelling in the current book market. I hope there can be space within the industry for both, with new and compelling fiction standing alongside retellings that reinvent themes and perspectives in a way the original novels could not. But I do wonder: as readers in frightening times, is our passion for the canon just another way of clinging to comfort?