You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Simplifying spelling is a mistake

The English Spelling Society’s proposal for a revised national system is deeply flawed.

Publishers should pay attention to the English Spelling Society, with its plans for a new English spelling system. The society, following meetings of its International English Spelling Congress, announced in November its decision to support the Traditional English Spelling Revised (TSR) system. The changes include removing redundant letters from words (such as "w" from "wrong") and minimising irregular spelling so that one letter or letter combination will only represent one sound. Founded in 1908, the society’s first members included George Bernard Shaw, and the group has until now never been able to agree upon a plan for an updated spelling system. The public will be tempted to view its current proposals as a harmless and eccentric scheme. This would underestimate the scale of the society’s ambitions: it aims to replace the traditional spelling system with TSR and this, from a publisher’s standpoint, is an alarming prospect.

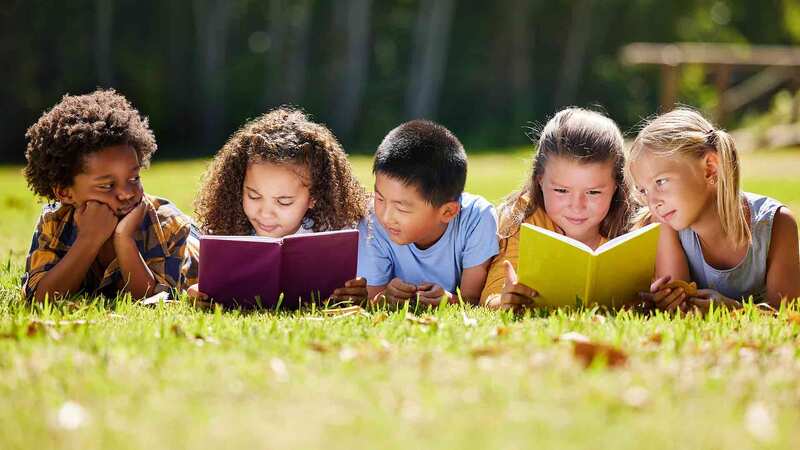

The society claims that its plan will combat illiteracy and boost the economy. It is true that illiteracy is an urgent problem in the UK: according to the National Literacy Trust, one in six adults in England and one in four in Scotland have "very poor" literacy skills. The society ascribes these concerning statistics to "the difficulty of teaching English and how long it takes to learn to spell properly". This does not account, however, for how well children do learn to spell if given the right resources. The best way to learn to spell is to read widely, and we know that children who grow up with access to books do better at school. Publishers can defend against the society’s proposed changes by supporting initiatives that will bring books to all young readers. Schemes such as the Free Books Campaign, founded by Sofia Akel in response to widespread library closures, are helping to bring books to those who need them most. However, more involvement is needed from large publishers, perhaps by donating print resources, to combat the scale of the illiteracy problem.

To strip the English spelling system of its rich irregularities would be to compromise the quality of the literature we publish, erasing the variety of histories and cultures that have informed the way we write words

As an industry, we have the tools to make English spelling comprehensible and accessible. There are success stories to reflect on: Elizabethan spellings in Shakespeare’s works, like "thou’rt" and "aught", can be understood by using editions such as the Cambridge School Shakespeare series, with their facing-page glossaries. And it’s not only student texts that remove the barrier of spelling. The best editions of Anthony Burgess’ 1962 novel A Clockwork Orange include a full glossary of Burgess’ strange words and spellings, so that the reader is equipped to understand and enjoy one of the most typographically irregular novels in the English language. Illiteracy is not the fault of the spelling system, nor will revising it solve the problem; instead, it is caused by a widespread lack of access to printed resources. When families have access to books, children are encouraged to read out loud and practise, until spellings don’t seem strange anymore. Books mean that education isn’t limited to a classroom setting.

Instead of promoting literacy, the society’s proposed changes threaten to impoverish and confuse it. There is scant evidence for an economic benefit, not least because a new spelling system would throw the publishing industry into disarray. This would compromise publishers’ ability to support initiatives that bring books to learning readers. On its website, the society claims that its changes wouldn’t lessen the value of printed books, because they would become prized for their rarity. What, however, of publishers’ backlists that are reprinted year on year? In the event of a transformation of our spelling system, a colossal logistic and financial challenge would fall to individual publishers. The task of updating all their editions would place especial strain on small presses, whose time and resources are already stretched. At best, such presses would have to divert their energy away from efforts to make their books more accessible. At worst, they would face the prospect of having to stop reprinting backlist titles, making reading material even more expensive and unevenly distributed.

Publishers should be wary of the society’s proposed changes and indeed prepared to defend this assault on the way speech is represented. To strip the English spelling system of its rich irregularities would be to compromise the quality of the literature we publish, erasing the variety of histories and cultures that have informed the way we write words. To standardise spelling according to a single sound takes no account of regional accents and the patina of historic pronunciation: who would decide that "bath" trumps "barth", or vice-versa? Learning to spell is not simply a tiresome inconvenience; it demonstrates how language is a product of our society’s diverse and complex heritage. Publishers have the resources to support learning, so that the completion and enjoyment of this process is not denied to anyone. On aesthetic and pragmatic grounds, the industry must oppose the English Spelling Society’s proposals.