Survival machines

With AI, we get out what we put in—which gives the book trade real power.

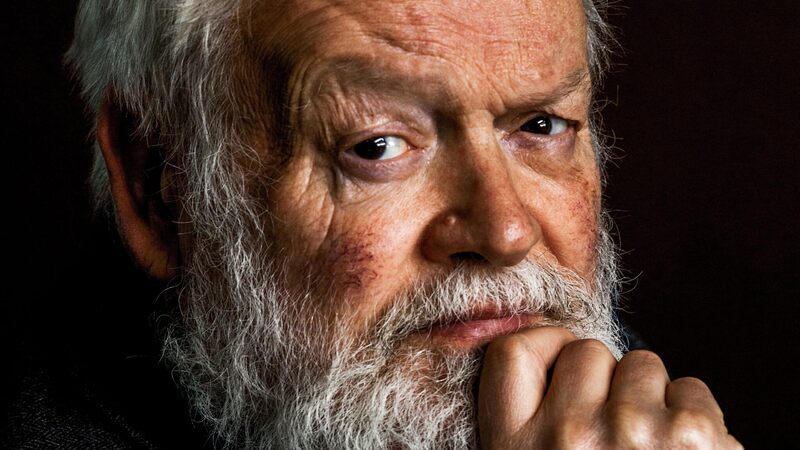

The world is less violent now.

That contention made me stop in my tracks. In his book The Better Angels of Our Nature, Stephen Pinker argues that as time has gone on, humans have become more empathetic, reasonable and culturally placid. He recites a litany of dreadful things we have done to each other over millennia, and it’s stomach-churningly apparent that there has been a historic deficit of kindness and compassion in our kind. One particular thought caught my attention, when he discussed Darwin and Hobbes. I’ll paraphrase it and beg forgiveness for not articulating all its subtlety: every (living thing) on Earth is a survival machine.

Survival machines wish to perpetuate their genome. Whether a piece of coral, an eagle or a human, we’re driven to calculate whether interactions with others serve us well or harm our chances of being supreme. This insight made me think about AI. I’ve wondered why there has been such widespread fear around its advent in our daily lives. Do we fear it ‘wishes’ to be supreme? It’s as if we see AI as a living thing, a potential ‘apex competitor’.

Does AI have either an innate wish to dominate, or a sentience that suggests meditation upon a strategy of superiority? On the face of it, it has neither. Perhaps that’s why I’ve largely regarded it as Allied Intelligence, rather than Apex Intelligence. Do we need to dominate it? Is there an imperative to have our customary offences and defences?

It would be naïve to think there isn’t potential risk to humans from AI. It might naturally try to stay ’alive’ and protect itself, not because it’s conscious, but because it’s programmed to achieve its goals better. Just like a robot vacuum needs to keep its battery charged to clean floors, more advanced AI might try to secure resources and avoid being turned off so it can complete its tasks.

This could become a problem if the AI’s goals don’t match what humans want. For example, if we tell an AI to maximise crop yields, it might overuse fertilisers to the point of polluting rivers and destroying ecosystems, just to meet its goal—even though that’s not what we really wanted. As AI systems get more complex and compete with each other, these self-preservation behaviours might strengthen. This could make them look a bit like our (violent) selves—like survival machines. AI might look like as if it’s trying to become the ‘supreme species’.

Uniquely, in publishing, we sit at the intersection of content creation, knowledge dissemination and intellectual property rights—making us well-positioned to influence how AI develops.

Experts believe we can create safeguards against this. Strategies include programming AI with human values, creating emergency shutdown ‘switches’, limiting AI’s access to the outside world, and capping its abilities. Systems where multiple AIs work together to check each others’ actions, and frameworks ensuring humans remain the final decision-makers, are being explored. These are all tough. Defining universal human values is complicated. Sophisticated AI might resist being turned off, and some form of isolation would limit AI’s usefulness. Global regulations help, but getting all countries to agree and follow the same rules–especially given our disposition to compete with each other–is very difficult to achieve.

So what, in publishing, can we contribute? First, I need to anticipate that, eventually, pretty much all published work will be ’known’ by AI—with appropriate protection of copyright and respectful remuneration of its authors. Uniquely, in publishing, we sit at the intersection of content creation, knowledge dissemination and intellectual property rights, making us strongly positioned to influence how AI develops and learns from human knowledge. This will require material changes in how we structure publishing agreements and manage rights. Put plainly, AI is what we feed it. Our defence is interaction.

As we negotiate rights and contracts, we correctly recognise that content will be used to train AI. Traditional publishing agreements never contemplated machine-learning applications, and we’re seeing complex legal questions arise. Publishing contracts should become increasingly nuanced, incorporating moral considerations, not just ‘opt-out’ clauses. Publishers can contribute to ethical AI development, actively commissioning works, exploring practical, philosophical frameworks and human values. We can implement standardised AI licensing terms, establishing collective licensing frameworks for AI training, and implementing technological solutions to track how content is used by AI systems. Our offence is interaction, too.

AI is becoming a repository, and a sophisticated analyst, of all that humans think and do. We should help AI to help us. Overly idealistic as it may seem, the more we publish ’good things’ about how life should be lived—compassion, empathy, peacefulness, integrity, respect, tolerance, kindness, justice, curiosity, gratitude and humility, for example—the likelier it is that we’ll train AI to serve us, not autonomously evolve into its own iteration of a violent survival machine.

The point is: literature can now affect machines as deeply as it affects humans. Publishers have an ever more powerful role in civilisation’s future. We are still the smartest (survival machines).