You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

The editor's dilemma

Too many white editors are failing to unlock the full potential of their non-white authors.

I was having a conversation with a friend of mine the other day, and we were discussing a recent book we had both read. This was a second book by an author whose first we had both loved. Odd, then, that we found the second book to be so bad. Overly long, disappearing plotlines, odd dialogue, a terrible ending. It was as if it simply hadn’t been edited. We both came to the conclusion that perhaps the success of the first book, which had been monumental (bestseller lists, the announcement of a big TV adaptation), had meant the editor no longer felt they could edit this author.

As we were talking, our conversation shifted, into an editor’s role in the shaping of an author. As an editor, I have, by several of my authors, been called "a pusher". One of my authors once had what I can only describe as a tantrum because I had told them the synopsis they’d sent me for their next book wasn’t as good as it could be. I wanted them to do better, because I saw my role, as their editor, to push them to grow with each book. Find something different, challenge the horizons of their writing, embrace the new. To leave the comforts of their old writing in the hope that they might find something that excites them and, subsequently, excites their readership.

This is something I believe applies to me, too, as an author. I have just reached the end of editing my second book, one that I rewrote three times before settling on the shape of it now. In the editing of said book, I rewrote it another three times, each time carving out something better, more defined, more aligned to what I saw in my mind. This rewriting was not just of my own volition, it came from my editor too, who read draft after draft and told me where she thought I was holding myself back, where to go further, where to hold. I wrote with her guidance, and it was together that this second book was created.

Today, the role of an editor is wide. We are not just expected to acquire, edit and publish books, but to be their cheerleaders in publishing houses that are publishing more and more books every year. We are expected to remember not just our own schedules, but those of publicity, marketing, sales, rights and art, to push those departments, gently but firmly, to remember our books. To make sure our authors aren’t being pushed to the side for whatever big release is coming out sooner than we all thought, to fight for their works to get some light. We are project managers, fingers jammed into every pie.

So perhaps it is understandable for editors to not want to push their authors too. After all, we’re doing so much of it in the office, where is the time to do it to our own authors as well?

An author does not grow if they are not edited, if they are not pushed

But here is where things get complicated. Because editors choose where to spend their time and where not to. For the author whose second book my friend and I deemed not as good as the first, an editor had decided it wasn’t worth the energy, for whatever reason (I imagine the huge success of the first book was a major factor), to push the author to reconsider its length, its numerous side-plots, its passivity. An author was let down, in part, because they were too successful.

Perhaps, my friend volunteered, they were let down too because they were non-white.

At first, I bristled at this, perhaps not wanting to accept the insidiousness of my friend’s comment. After all, I said, their first book was clearly edited and was a huge success. But as I sat there and we spoke more, I thought about some things I had seen happen, in publishing houses both big and small, by white editors to their non-white authors.

First, I saw the problem of editing too much. White editors go into a book, fail to understand something, and ask questions that the author will then feel compelled to answer within the text itself. These are oftentimes things that are self-explanatory to the people who exist within the same context of the author. For those of us who do not belong to the same context, well, I would say it is never so hard to read between the lines or, if we feel so compelled, to go to the internet. These over-explanations are then caught by the community the author themselves is from, and is often writing for, and the author is accused of having written this book for a white audience, of betraying their people. More than that, it makes for, at best, a mediocre reading experience; at worst, a terrible one.

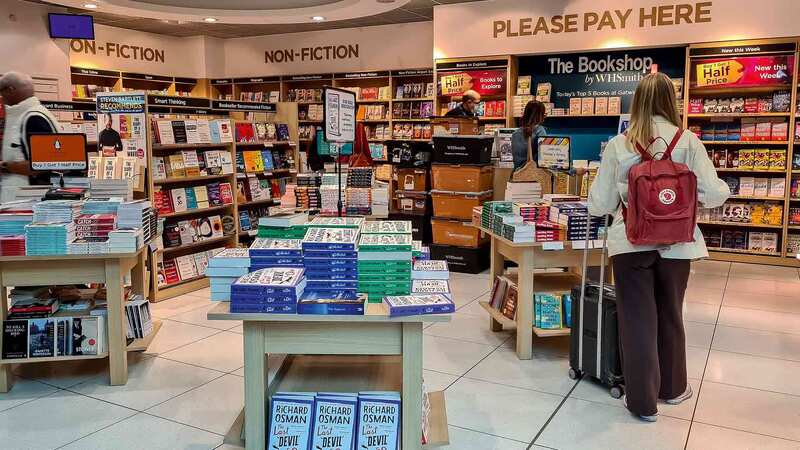

Second, there is the other side of the coin: white editors buying books, intentions good or otherwise, from non-white authors and then simply doing a copy-edit. They tell themselves, and whoever will listen, that they are being good allies for not asking too many questions, for not asking an author to explain themselves. They say, who am I to question the experience of this author, this community, this people. But in stepping back so much, they fail their authors. An author does not grow if they are not edited, if they are not pushed. I once watched an editor buy a book from a Black author, in the wake of George Floyd’s murder – a hurried acquisition in their attempt to have something "diverse" on their list – then not edit that author, fail that author in a dozen other ways and subsequently complain that the author’s second book had the "same problems as the first". I bit my tongue then but what I should have said was: perhaps this time, you should do your job.

Third, and this is the more insidious problem, white editors will read these works and not quite understand them. This goes far beyond a simple question of a cultural trait or a phrase, but to the actual structure, style, tone of a book. Perhaps an ending feels too incomplete, there is no easy resolution, or maybe a character feels too opaque, or the author is simply engaging in a literary tradition the editor does not know of. Two things happen here: one, an editor may decide it is simply too challenging to publish this book so they reject it, not because it is a bad book but because it is "not for them", ergo, "not for the market", ergo, "not to be read"; two, they acquire the book and then hammer it into a shape that is recognisable to them, removing an author’s intent from their very own works.

It is, of course, not just white editors who behave this way to non-white authors. Wherever there is a difference, these things are likely to happen. An able-bodied editor may act a similar way to a disabled author; a straight editor to a queer author; a man to a woman. I, a Pakistani Muslim editor, could behave the same way to, say, a Black author.

But, in my limited experience of working in the publishing industry, I have seen this dynamic most at play when it comes to matters of race, and from editors who are white.

So, I hear white editors proclaim, hands thrown into the air, what are we to do? To that, there is no easy answer, no simple resolution. Only that I would hope that if they see some of themselves in the above three points, they would attempt to reckon with them. To reckon with the reasons for wanting to publish a book, how they want to work with their authors, to see all works as equal of the same editorial work. To push authors to learn and grow, but not push them to change simply because it is easier. To communicate, have conversations, and do the work of treating your non-white authors and their books as you would treat your white.

To authors who may see themselves on the flip side of these points, I would say this: it is your work, your name that goes on the book, but it is only ever one of an editor’s list. Fight for yourselves, always.