You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

The fight against misinformation is on

... and publishing needs to arm itself.

Online misinformation finally captured mainstream attention in the UK in 2024. From the role played by lies spread on social media in the Southport riots, to the growing influence on a generation of young men from influencers such as Andrew Tate, alarming stories hit the headlines on a regular basis.

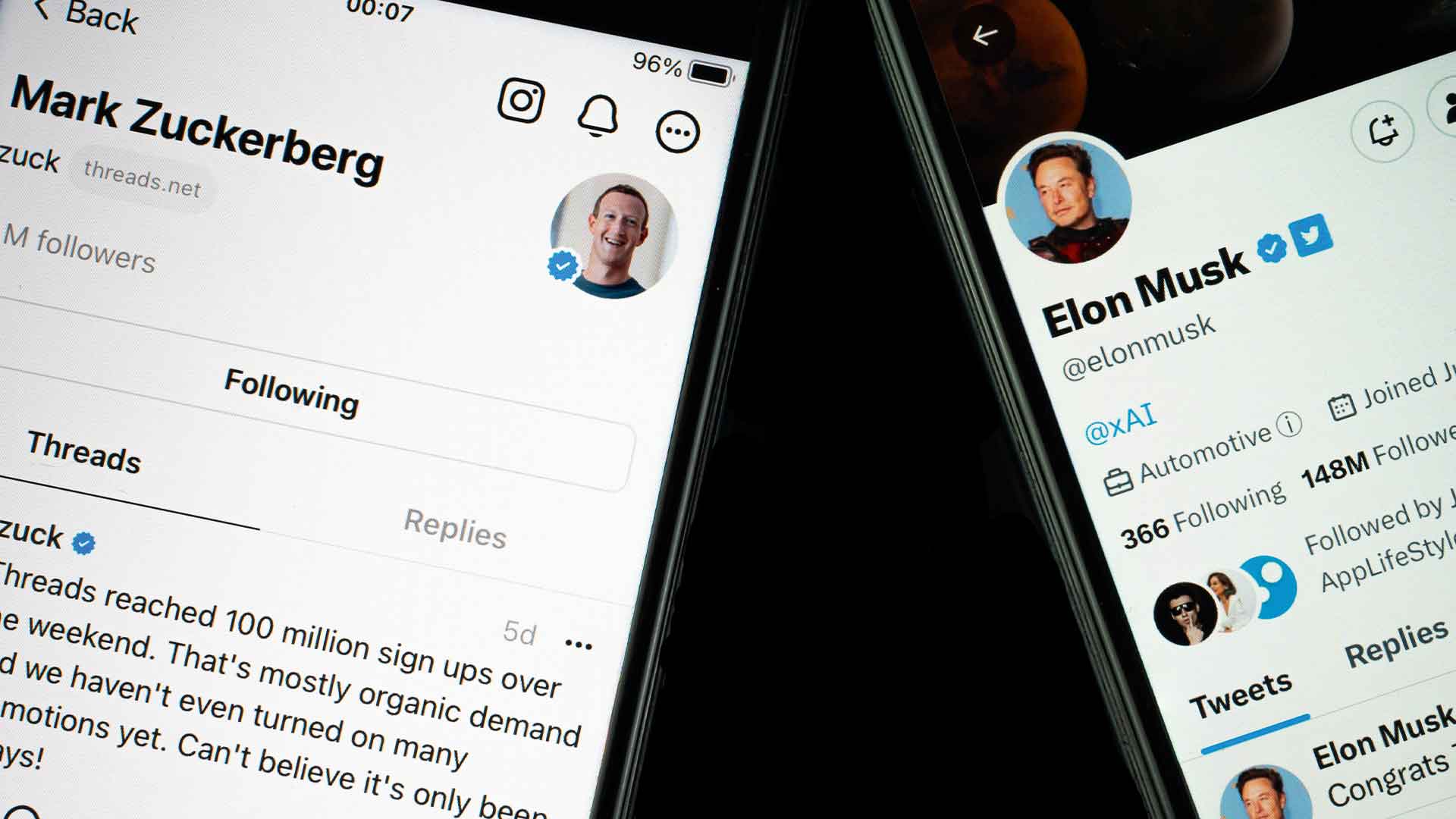

Now, on their platforms, Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg have consigned fact-checking used daily by millions to the dustbin of history, potentially exposing social media users to a torrent of algorithmically driven lies.

As I leave publishing to move into a new role as head of strategy and communications at Shout Out UK, an organisation founded to promote political and media literacy, I’ve been reflecting on the role that publishers can play in the fight against this flood of online misinformation.

Book publishers, historically trusted purveyors of fact-checked quality information, should be in prime position to stem this tide, helping readers distinguish truth from falsehood and, in turn, strengthening our democracy.

Books by authors such as Maria Ressa, Shoshanna Zuboff and Naomi Klein among others have done much for my own understanding of how our media landscape has been transformed into a system where maximising revenue for a few billionaires is prioritised over representing reality.

But in an information environment which moves at the speed of a TikTok, the industry urgently needs to do more to advocate for fact-based discourse.

First, face up to the reality that your engagement on social media, particularly in the form of paid advertising, is bankrolling a system which often monetises misinformation.

Publishers have used social-media communities since their inception to share news and recommendations and exchange opinions. The power of TikTok virality to drive sales has created dozens of bestsellers and many bookshops use the app brilliantly to attract young customers.

During summer’s general election campaign, however, the BBC’s Marianna Spring found that young voters were bombarded with misinformation on TikTok, including AI-generated videos featuring party leaders. With the app currently the UK’s fastest-growing news source, this should concern us all.

It is time for some serious engagement with the new realities of our media environment – the long-term sustainability and credibility of the publishing industry depends on it

Elon Musk’s acquisition of Twitter in 2022 has turned the global town square into a propaganda platform for the political agenda of the world’s richest man, which apparently includes inciting Britons to overthrow their democratically elected government. This, combined with the algorithmic manipulation which sees Musk’s divisive tweets rise to the top of users’ feeds, has seen users leaving the platform at the rate of a million a month.

Perhaps the biggest win for misinformation was last week’s announcement from Mark Zuckerberg that Meta will be rolling back its moderation and third-party fact-checking processes (characterised by him as censorship), with a nonchalant acknowledgement that this "means we’re gonna catch less bad stuff". Not reassuring to those who have been following Ian Russell’s campaign to call Meta to account for the stream of harmful content he claims triggered his daughter Molly’s suicide in 2017.

At present, Meta’s roll-back applies only to the US. It remains to be seen how these developments would be met in the UK by Ofcom’s new powers under the Online Safety Act to force tech providers to moderate the content they distribute. However, the Government’s Science Secretary himself, Peter Kyle, admitted this week that he believes the regulation is insufficient to deal with ever-increasing amounts of online disinformation and violent and disturbing material. With the search "How to delete Facebook" currently trending, publishers need to act fast.

Pan Macmillan appears to date to be the only large publisher to have withdrawn from X [formerly Twitter] completely, but I don’t believe total disengagement is the answer either. If all moderate voices flee to distinct online silos, societal division will only continue.

Instead, publishers and authors – some of whom have huge followings – must critically engage with X and Meta, challenging misinformation where they find it. Marketers should of course also explore all the alternative social media platforms and use every chance to increase their author brands’ newsletter acquisition (including sign-up opportunities at all author events). Substack is seeing huge growth and is another opportunity to target readers directly in their inbox. Continue to advertise with media brands which still uphold the norms of objective journalism. And above all, support all efforts to increase real world engagement with books and literacy – including media literacy – in libraries, education, bookshops and festivals.

Publishers and authors – some of whom have huge followings – must critically engage with X and Meta, challenging misinformation where they find it

Secondly, it is time to consider the wisdom of platforming authors who spread misinformation. Publishing must of course champion freedom of speech and reflect a wide plurality of views, but publishers need to accept that signing authors whose views extend to harmful and false conspiracy theories is more than just a reputational risk. The books of authors who have been found to spread misinformation, including such bestsellers as Neil Oliver and Steven Bartlett, may be thoroughly fact-checked in-house to ensure their truthfulness, but is giving them space on your list lending these figures a public legitimacy they may not deserve? Bartlett’s response to Meta’s announcement this week was to use a LinkedIn post to suggest that digital platforms were right to "decentralise ’truth’". The inverted commas speak volumes. Publishing authors who are known to spread misinformation devalues books as a trusted source of information, and with non-fiction sales already in decline, will also lead to a commercial dead end.

Finally, ensure that your publishing teams are thoroughly media literate themselves. As the online environment becomes more unmoderated, it will be increasingly hard to spot where content is AI-generated, cobbled together from untrustworthy, sometimes plagiarised sources, or outright untrue.

Authors have already discovered AI is being used in their marketing without their or, seemingly their publishers’, knowledge. How adept are your employees at navigating this new world? I discussed this yesterday with Shout Out UK’s founder Matteo Bergamini who commented: "Media literacy is no longer just nice to have. In a digital world where fact and fiction become easily distorted, publishers need to step up and partner with media literacy organisations to ensure that truth and critical thinking do not get condemned to the history books."

I believe it is time for some serious engagement with the new realities of our media environment – the long-term sustainability and credibility of the publishing industry depends on it.