You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

The literature of loneliness

Michel Houellebecq’s books succeed against all odds because they reflect our great modern malaise.

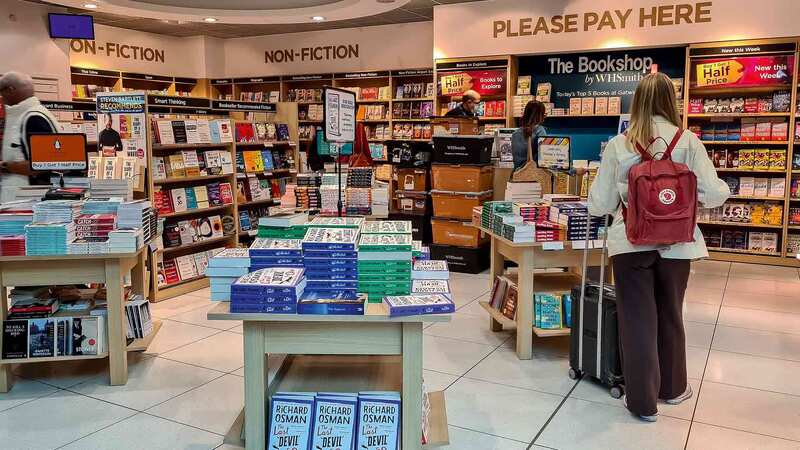

You can say what you like about Houellebecq, but he’s offering great value for money. With 544 pages for £22, his latest novel, Annihilation (Anéantir) is a great bargain if you measure a book’s literary worth by its weight.

The story itself, however, is a more complicated matter. A middle-aged civil servant plans a clandestine expedition to rescue his father from hospital. Then there’s the occult satanist conspiracy to drown migrants crossing the Mediterranean sea on small boats. And the fan fiction revolving around former Ministre de l’Économie Bruno Le Maire’s sex life. Worry not, though: these three storylines vanish entirely when the main character discovers he is terminally ill and starts wondering about life, the universe, everything.

Why do so many of us buy Houellebecq’s chaotic and depressing novels? The reason is certainly not his clever stances on the French political life: an advocate of the Great Replacement theory, according to which unnamed elites are organising mass immigration to get rid of traditional European cultures, and a great fan of Donald Trump’s, Michel Houellebecq is a much-appreciated guest of far-right shows. But no matter what extravagant views he might be expressing in the media, Houellebecq’s books are invariably bestsellers.This, I suggest, might be linked with the pervasive presence of loneliness as a theme in Houellebecq’s writing: his political opinions might be bizarre, but he seems to have grasped a key theme in modern Western society.

That loneliness as a theme now spans our literature is a disturbing reflection of society.

Loneliness as a literary theme has a long history. It is sometimes depicted as an unavoidable side effect of living an artist’s life, along with poverty and poor mental health. Eating cold instantaneous noodles on your own up in a freezing attic is, it seems, inspiring. Baudelaire, the archetype of the cursed poet, writes about his at length in his Flowers of Evil. In Paris Spleen, the narrator of one poem called "Solitude" sees loneliness as the privilege of the artist: choosing social isolation implies your inner life is vivid enough to make other people optional.

Houellebecq himself produced theoretical writing about loneliness as a correlate of literary creation. In his early essay "Rester vivant, méthode", he compares the artist’s quest to walking through a beautiful, desolate palace: being lonely, however painful it might be, is considered the price to pay for enjoying the pleasures of creation—or even the source of it.

In his novels, however, Houellebecq writes about another type of loneliness, one not chosen, but suffered in silence. His books, it can be argued, aim at building a typology of deaths by despair: from the agricultural worker killing himself in Serotonin, to the main character of Annihilation refusing treatment that could cure his illness, the question of how to survive in an increasingly lonely world is the one recurring thread in Houellebecq’s work.

That loneliness is a crucial issue in Western societies has been acknowledged by the WHO. Lacking human contact has been shown to increase the risk in dementia, cardiovascular disease and early death. This state of things is reflected not just in Houellebecq’s success, but in many great names of today’s French-speaking literature. Elisa Shua Dusapin’s award-winning first novel, Winter in Sokcho, translated by Aneesa Abbas Higgins, depicts the dullness of daily life in an industrial port on the coast of South Korea. Her poetic and elegant writing pinpoints beautifully the absence of perspectives in the life of a young Korean woman working at a guest house. Shua Dusapin’s depiction of loneliness is soft, bleak and melancholy.

At the other end of the spectrum, Victor Dumiot’s novel Acide links social isolation with physical violence: a woman disfigured in an acid attack gives up on her social life, while a reclusive young man turns to extreme pornography and self-mutilation to relieve the solitude in his life. Victor Dumiot’s characters suffer on their own, in silence, with little or no help, and the author spares us nothing in his depictions of atrocity.

That loneliness as a theme now spans our literature is a disturbing reflection of society. It also means, however, that we can no longer ignore the elephant in the room. We can only hope future generations will no longer feel the need to elaborate at length on the topic.

As for me, I’ve found how to play my part: I’ll help relieve loneliness by joining a book club where I’ll grumble for hours about Houellebecq’s latest book. With such a topic, I’m sure I’ll make friends.