You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

The numbers game

In a society that privileges the achievements of fledgling young talent, we must not neglect the potential of women in middle age and later.

A Trade Union Labour Force survey in 2021 found that 11% of all people in employment, and 23% of all women—that is 3.5 million women—have experienced menopause. According to the NHS, menopause typically occurs between the ages of 45 and 55, with the average age being 51 years. One in 100 women in the UK experience menopause before the age of 40, however. Menopause also affects trans men, but unfortunately, we do not have enough data on this yet.

Despite this high incidence of menopause in the workforce, our places of work are still ill-equipped to support people during this key life stage: BUPA research from 2021 estimates nearly a million women have been forced out of the workplace due to menopausal symptoms. Globally, this loss of key workforce amounts to approximately $150bn a year. Most have departed because of the lack of support in managing the symptoms of menopause, and the implicit—and sometimes explicit discrimination—they have encountered.

Menopause discrimination intersects with the ageism that is rife in our society. Psychiatrist and gerontologist Dr Robert Butler coined the term “ageism” in 1969, and as with race and gender, it takes less than a second for age-based social categorisations to take place. These happen so automatically that they are difficult to pin down, but may involve cues such as wrinkled skin, grey hair, weight and posture, or symptoms of menopause such as hot flushes.

Nearly a third of women surveyed in a recent Chartered Institute of Personnel Development (CIPD) survey in the UK said they had taken sick leave because of their symptoms, and only a quarter felt able to tell their manager the real reason for their absence

Racism and ageism also intersect to heighten the menopause discrimination for Black and brown women. Research shows they routinely experience menopausal symptoms earlier than their white peers, and can face more severe symptoms, due to socioeconomic status and other stresses such as systemic racism, resulting in longer-term consequences on their mental and physical health.

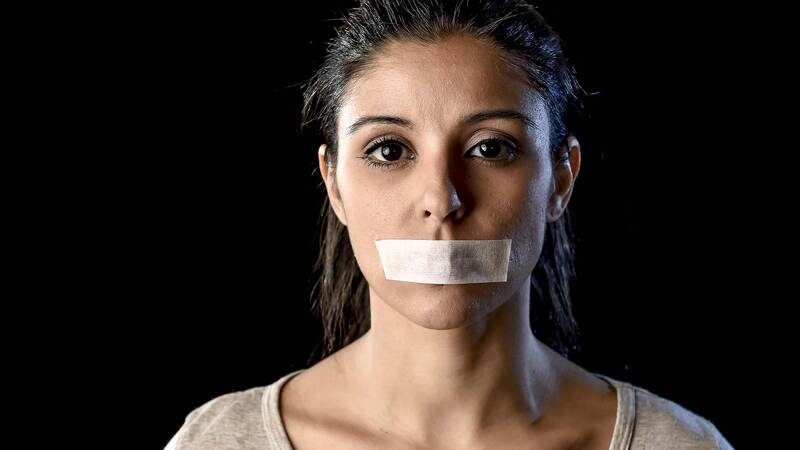

A fine line

Overall, the intersection of gender bias and ageism means that women are often forced to navigate a thin line between being “too young” and “too old”. Too young and they are deemed immature, or lacking in gravitas. Too old and they are considered “past it” and inefficient. As a consequence of such stereotyping, women often feel compelled to keep quiet about any peri-menopausal symptoms affecting their life and work. Nearly a third of women surveyed in a recent Chartered Institute of Personnel Development (CIPD) survey in the UK said they had taken sick leave because of their symptoms, and only a quarter felt able to tell their manager the real reason for their absence. This is more often the case when the manager is young and a man, but we know that women can discriminate against women too.

The fear of speaking up is linked to the fear of being perceived as old and hence not of value to the organisation. When we don’t talk openly about something, it acquires shame and stigma. And so, menopause becomes a condition that dare not say its name. The silence, and sometimes outright bullying, can lead to anxiety and depression in menopausal women and stifles the possibility of changing workplace practices and cultures.

The CIPD survey also found that 59% of women experiencing menopausal symptoms said they had a negative impact on their work, and around half of respondents found it difficult to cope with their tasks. In my consultancy role with global organisations, I have found that most workplaces do not have any policies to support people during these life changes. Sometimes these symptoms can be perceived as a barrier to productivity and to organisational image, rather than conditions that can be managed with adequate support.

Breaking the stigma

There is much-needed discussion of menopause in the media currently, but this must extend to workplaces. Organisations need to open up the dialogue around menopause, and have clear policies in place around support, mentoring and flexible working, if and when needed. There is also a need for inclusive language in these discussions because menopause affects trans men and gender non-conforming people too. Support groups in workplaces can help people facing these life changes and symptoms that affect them at work. Managers and leaders in workplaces need training in talking about menopause, and an understanding of how healthcare bias also impacts women during this time of life.

In the book industry, we routinely celebrate the young, the fresh new talent, the new voice on the block: with lists celebrating “30 under 30”, for example. While it is important to support and encourage people of all ages, this creates the perception that women over a certain age do not have anything meaningful to say or contribute.

It should not fall to women to overcome the biases and taboos they face—this should not be another emotional burden for us to carry. And women must be enabled to use clear language around their symptoms and be open about menopause. Using euphemisms or avoiding talking about it can perpetuate embarrassment and biases, as if it is something to hide or be ashamed about.

It is not, and so it is high time we were honest and open about it.