You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

The wonder years: why adults should read kids' books

Few grown-ups explore the children’s or YA shelves, but they’re missing out on stories that resonate across generations.

In April 2020 I found myself sat in my back garden, bathed in unexpectedly glorious sunshine. Amidst the chaos of the first lockdown – the closed shop, homeschooling, hurriedly built website and new career as a delivery driver – I found a few hours of peace. In fact, I found two afternoons of peace. The only time that has happened since having kids (I’m not sure how this happened, maybe they discovered Narnia in their wardrobe without my noticing).

On the first afternoon, I read The Story of a Brief Marriage by Anuk Arudpragasam, a meditative, poetic tale of personal connection amidst the horrors of a war-torn refugee camp. On the second I read Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane, a magical story of memory, childhood fears and the fallibility of parents.

Anuk Arudpragasam’s protagonist, Dinesh, is engulfed in the physicality of his body and the mutilated bodies around him. Days blur as survival becomes the only ambition. Neil Gaiman’s unnamed narrator finds himself negotiating a world where space, time and reality blur, where the monsters under the bed weave their way into the fabric of his life.

Reading them side-by-side, during the surreal novelty of the first and most severe lockdown, when my world had shrunk to my house and my bookshop, turned these individually brilliant books into a collective contemplation of what it means to be alive, to exist, to be human. Neither before or since have I read two books that seemed so perfectly, oddly, entwined.

Yet only one of them would stand a chance of featuring in The Big Jubilee Read’s list, of being named amongst other “great reads by celebrated authors from the Commonwealth”. The Ocean at the End of the Lane would immediately be discounted due to its classification as a children’s book (Anuk Arudpragasam’s second novel, the Booker short-listed A Passage North, is on the list).

For all that we encourage our children to read, and bemoan the distraction of screens when they don’t, we’re quick to disregard children’s books for ourselves. We see them as less important, of less artistic value, than books written for adults.

Any list of books, art, music, even potato-based foodstuffs will, by its very nature, have omissions. And every list will, by its very nature, annoy somebody, somewhere. I’m not annoyed The Ocean at the End of the Lane isn’t on the list but I am perplexed why children’s books were not even considered due simply to them being children’s books.

Most readers discovered their love of reading during childhood. Most people who choose not to read as adults will have had, however briefly, a favourite book as a child. We may fall in love with certain stories as adults, but it’s rare we do in the ravenous, stay-up-all-night-reading-under-the-covers, world-changing way we do as children. We don’t adopt the characters of Shuggie Bain or Wolf Hall as our imaginary friends or wished-for siblings (often in place of our actual siblings). We don’t dream of becoming detectives after reading Slow Horses in the same way we did after reading The Hardy Boys.

For all that we encourage our children to read, and bemoan the distraction of screens when they don’t, we’re quick to disregard children’s books for ourselves. We see them as less important, of less artistic value, than books written for adults. Outside of booksellers and publishers, and even inside of them, how many of us would read a children’s book purely for our own entertainment? Very few, I’d imagine.

That’s a great shame, because we’re missing out on thousands of truly great stories. The odd one sneaks through, covertly, slightly ashamedly, under an invisibility cloak, hidden inside the jackets of a more "grown-up" book. But the vast majority never find their way onto our shelves, into our hearts.

I think there’s something simple we, as booksellers, can do about that though. Something that will take us all of five minutes. We can include some of the books we section off for children or teenagers amongst our adult titles. We can file Neil Gaiman next to Damon Galgut, we can place Katherine Rundell alongside Arundhati Roy. We can recommend Dean Atta’s The Black Flamingo and its mix of prose and poetic form, in the same stylistic breath as Max Porter’s Lanny.

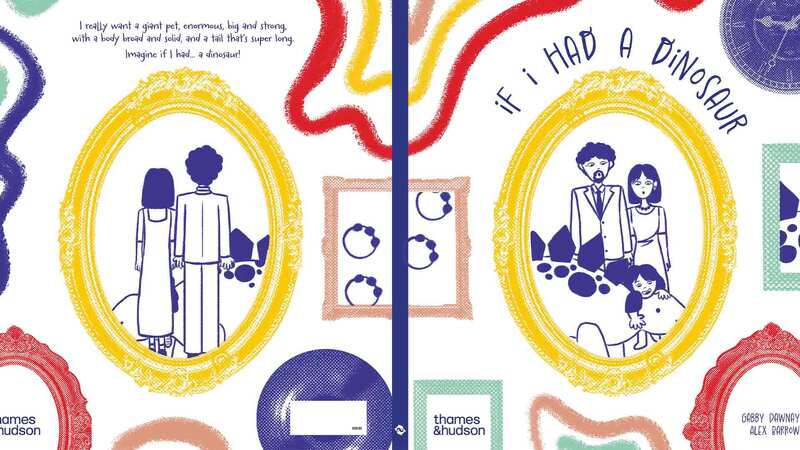

We may need some help from publishers – alternative covers for the children’s books that sit more subtly against their adult counterparts – but we can at least start recommending children’s books to adults without these. We’ll likely get knocked back by most customers, as they’ve had decades of being told children’s books are for children, but since when has having suggestions turned down stopped us? Just like a small boy named Harry, who crossed the mythical, "children’s book to adult hands divide" – rejection only makes us stronger.